Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World (28 page)

Read Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World Online

Authors: David Keys

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #Geology, #Geopolitics, #European History, #Science, #World History, #Retail, #Amazon.com, #History

Soon the Soga discovered that the main remaining anti-Buddhist opposition element, the Mononobe clan, was planning a coup, so in a ruthless preemptive strike, the Soga and elements of the royal family massacred the Mononobe. Some were killed in battle, while others appear to have been rounded up and executed. At one execution site, a dried-up riverbed, hundreds lay dead. “Their corpses had become so rotten that their identities could not be ascertained, but by the color of their clothing their bodies were identified for burial by their friends,” says the

Nihon shoki.

By 590 numerous Buddhist temples were being built, and it seemed that with the anti-Buddhist opposition liquidated, the Soga position was secure. But the new king, Sujun, seems to have wanted a greater degree of independence from his Soga minders and was reportedly gathering armaments in his palace. So once again the Soga launched a preemptive strike, this time murdering the king himself. He was the clan’s second royal victim, the first having been Senka, half a century earlier.

With King Sujun disposed of, a pro-Soga monarch and enthusiastic Buddhist—a powerful lady called Suiko—was placed on the throne.

8

She had much experience of power politics, being the daughter of King Kimmei by a Soga wife and having been married to the former King Bidatsu. Her nephew—a prince called Mumayado (later, posthumously, known as Shotoku)—was also pro-Buddhist and pro-Soga.

The great ideological and political conflict for the soul of Japan, which had begun in the 530s, was now almost over. The traditionalists and isolationists had lost and the pro-Buddhist, pro-foreign reformers had won. Over the next twenty years, religious, political, economic, administrative, fiscal, artistic, and calendrical ideas were imported wholesale from the Asian continent, mainly from China. In 603 a more meritocratic system replaced the traditional hereditary hierarchy at court. In 604 Chinese Confucian principles of harmony, duty, and decorum were introduced. In 607 the first Japanese embassy was sent to China. Soon students were going to China to study. Deliberately copying the Chinese emperor, Queen Suiko even styled herself the “heir of heaven.”

In a sense, Buddhism had been merely the Trojan horse within which all these other changes were waiting to enter Japan. The process that had been kicked into motion by the climatic and epidemiological events of the 530s had been completed by the early seventh century, and Japan was an utterly different place from what it had been in the early sixth. Ancient Japan had died, and protomodern Japan had been conceived. Today’s Japanese nation-state has its distant yet essential origins in the tragic yet catalytic sixth century.

CHANGING THE

AMERICAS

C O L L A P S E O F T H E

P Y R A M I D E M P I R E

J

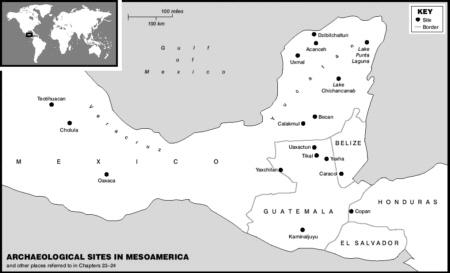

ust as Europe, the Middle East, and the Orient had experienced massive geopolitical change in the century following the climatic disasters of the 530s, so too did the Americas. Both in Mesoamerica and the Andes, there was a total geopolitical realignment, driven ultimately by the engine of climatic change. In North America and in non-Andean South America, the sixth century was also one of transformation—an era of new beginnings.

When the Spanish, under the conquistador Hernán Cortéz, conquered Mexico between 1519 and 1521, they stumbled upon the deserted ruins of a vast city with wide avenues, great plazas, and huge pyramids—the largest of which was almost as big in terms of volume as Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Cheops. The Spanish conquerors asked the defeated Aztecs to tell them who had constructed such magnificent buildings. The Aztecs replied that the deserted city had been the Place of the Gods (Teotihuacan in Nahuatl, the local language), and that it had been built long ago by a race of giants. To prove the truth of this latter assertion, they produced what they claimed were massive thighbones of these gigantic supermen. However, unbeknownst to both the Spanish and the Aztecs, the giant thighbones were in fact those of an extinct species of prehistoric elephant.

But it was an understandable error, given the sheer scale of the pyramids and the ruined city they lay at the heart of. The largest building was the vast Pyramid of the Sun—a towering 215-foot-high mass of over 1.2 million tons of rubble and sun-dried mud bricks. The city itself covered eight and a half square miles, and modern archaeologists now estimate that it must have been home to between 125,000 and 200,000 inhabitants.

The Spanish account of what the Aztecs told them about the Place of the Gods is the earliest historical information that exists about Teotihuacan. And yet archaeological investigations of the site have now revealed that the city had been deserted almost a thousand years earlier—at virtually the same time that saw population collapse in so many places in the Old World.

In the early sixth century Teotihuacan was at its peak—a flourishing metropolis, the heart of an economic, ideological, and probably partially military empire that had as its sphere of influence the southern half of Mexico and much of what is now Guatemala and Belize. It was a heterogeneous empire of different peoples, tribes, and states. Some were conquered tributaries, while others were long-term allies or client states who probably would never have dared defy the hegemony of Teotihuacan.

The empire was bound together by religious ideology and by trade. With its huge number of inhabitants, the city was by far the largest population center in the Americas. Indeed, at the time, Teotihuacan was the sixth largest metropolis on earth. It must have sucked in vast quantities of imports from all over Mesoamerica. And it must also have pumped out substantial quantities of exports and reexports.

The livelihoods and economic survival of several million Mexicans and Maya depended on the maintenance of Teotihuacan and its power. The city was the heart of ancient Mesoamerica’s equivalent of today’s steel industry—the mass manufacture of millions of artifacts made of volcanic glass (obsidian). Artisans in dozens of workshops worked in what was probably a partially state-controlled industry to produce a wide range of obsidian items—everything from spearheads and blowpipe darts to knife blades and exquisitely made human figurines. Hundreds of other workshops specialized in making baskets, mats, pottery, and textiles, as well as jewelry made out of imported seashells and sculptures made out of basalt.

The construction industry must also have been substantial. To provide the raw materials for dwellings for up to two hundred thousand people, let alone the specialist skills to repair and intermittently replace them, and to build and maintain dozens of often vast public buildings, would have required a large workforce to extract and make lime, make bricks, cut stone, obtain and work wood, and paint the frescoes that adorned the interior walls of so many houses in the city.

Other industries that would also have flourished—albeit on a smaller scale—must have included mica and feather working and papermaking. Although no actual paper has survived in Teotihuacan, the technology for manufacturing it did exist in Mexico at the time, and stone paper beaters have been unearthed on the site. Made from the pounded inner bark of particular types of trees, paper would have been used not just for writing on, but also for making ritual clothes and jewelry and as an easily inflammable base on which to daub incense, rubber, and blood to be burned as offerings.

There was also a large merchant community in the metropolis; archaeological evidence suggests that entire suburbs of foreign merchants and artisans existed. The import business was on a truly massive scale—a remarkable feat bearing in mind the substantial distances involved and the complete absence of wheeled vehicles or even pack animals.

Seashells (for making jewelry) had to be imported from the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific coast, 150 and 180 miles away, respectively. Rubber (for balls) had to be obtained from Veracruz, on the Gulf coast—and Guatemala, 500 miles to the east. Much of the cotton textile needed to manufacture clothes also probably came from the Maya regions far to the east, and from the Oaxaca and Veracruz areas, respectively 270 and 150 miles from Teotihuacan. Feathers—including those of the green-blue quetzal—had to be traded from the jungle areas in or near what is now Yucatán and Guatemala. And minerals used for making paint pigments were obtained from the north; some cinnabar, hematite, and malachite came from mines, probably controlled by Teotihuacan, hundreds of miles away from the capital. But the most exotic of all imports, turquoise, had to be obtained from what is now the northern part of New Mexico, 1,200 miles away.

Although a good 30 percent of the population was probably involved in craft or manufacturing activities, most of the remainder, the great majority, would have been agricultural workers. Whether agricultural land was owned by individual families, larger kinship groups, or by the state itself is not known. However, archaeological survey work has yielded settlement data that suggests that the population was concentrated in the metropolis as a matter of deliberate political policy.¹ In the countryside for miles and miles around Teotihuacan and its immediate vicinity, there were very few settlements. It appears that almost the entire population of the surrounding two hundred square miles had at some point been forced to live in the city, thus preventing the development of any potential rival population centers. This politically induced phenomenon of rural depopulation must have led not only to overintensive use of farmland within walking distance of the metropolis, but also to underuse of potential farmland beyond the city’s immediate environs.

Agricultural prosperity was not only at the heart of the city’s—and the empire’s—survival; it also lay at the core of Teotihuacano religion. The most important deity was almost certainly the rain god Tlaloc, who not only was seen as the power behind rain, thunder, and lightning but was also closely associated with the staple food (maize) and aspects of creation itself. He was believed to take the form of a fanged animal, perhaps a roaring jaguar or raging crocodile, who lived in a deep cave inside a sacred mountain. Yet he was also seen as being immanent within the clouds themselves.

It’s not known for sure which temple at Teotihuacan belonged to Tlaloc, but the prime candidate is probably the vast Pyramid of the Sun—the largest structure in the city. In 1971, almost twenty feet beneath the 215-foot-high pyramid, archaeologists discovered a man-made passageway over three hundred feet long leading to a mysterious cloverleaf formation of four subterranean caves. There they found ducts for channeling water through the caverns and evidence of ritual activities, some of which even predated the building of the pyramid itself. The known primacy of Tlaloc at Teotihuacan, the caves underneath the pyramid, and the presence of channels to carry water combine to suggest that Tlaloc was probably the deity to which this huge structure was dedicated.

Water lay at the heart of Teotihuacan’s politico-religious and economic systems. Indeed, the Nahuatl words for “water mountain” (referring to the extinct volcano that dominates Teotihuacan and which still gurgles with the sound of water trapped inside it) and “community/city” are one and the same,

altepetl.

The three most important deities, Tlaloc (the rain god), the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl (also linked with rain and water), and the Mother of Stone (the personification of the water mountain) were all associated with life-giving water.² The link between rain and agricultural fecundity was symbolized by Tlaloc’s association with corn, the city’s staple food, while Quetzalcoatl’s traditional association with the ideology of divinely sanctioned rulership underpinned the political aspect of Teotihuacano religion.