Catherine Price (19 page)

Authors: 101 Places Not to See Before You Die

I

t’s never fun to go to the Department of Motor Vehicles, the government bureaucracy better known as the tenth circle of hell or, and I really did hear this once, Satan’s asshole.

That might be a little harsh. But regardless of which of Satan’s orifices you decide to compare it to, there’s no denying that much like the Dementors in

Harry Potter

, the DMV has a singular ability to suck people’s will to live. And everything’s worse on Monday, from the lines and crowds to the moods of the people who work there.

My favorite part of my local branch is that you have to wait in line to get a ticket telling you which line to wait in. But that’s nothing compared to the experience of Laura Zhu, whose DMV disaster ended up on

AOL Money

:

Newlywed Laura Zhu tried to get a license with her maiden name as her second middle name. When she explained this to the DMV worker at a New York City office, Zhu says the woman yelled at her, “You have to hyphenate if you want two last names!” After speaking with a supervisor and finding out that it is indeed state policy to hyphenate, Zhu says she was sent back to the same window. That’s when things got ugly. “Little Miss Doesn’t-Want-to-Hyphenate wants a license now,” the clerk announced loudly, then proceeded to sing a little tune as she worked: “Anderson hyphen Zhu! Anderson hyphen Zhu!”

It’s enough to make you want to take the bus.

B

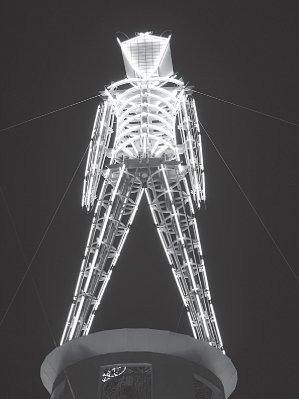

lack Rock City is the home of Burning Man, a giant art festival held each year in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert. For devotees, Burning Man can be a life-changing experience, a chance to break free from societal norms and spend a week indulging in so-called “radical self-expression” in a giant, impromptu community. But if you don’t enjoy being surrounded by drugs and naked people coated in glitter, you probably should not attend.

For starters, the festival is huge. The first Burning Man, held in 1986 on San Francisco’s Baker Beach, drew twenty people. These days, it attracts around fifty thousand. To accommodate these revelers, every year Burning Man’s organizers construct a temporary civilization—Black Rock City—on the desert’s playa, an ancient lake bed. They set up a circular settlement centered around a giant anthropomorphic sculpture called “the Man” that is set on fire on the festival’s last night and gives Burning Man its name. At the end of the weeklong party, the entire city disappears.

Burning Man’s organizers provide emergency medical services and Port-O-Potties but that’s about it—visitors have to bring everything they need to survive in the desert for a week. This is known as “radical self-reliance.” To make things especially radical, no commerce is allowed in Black Rock City, and the only way to obtain things you don’t already have is through “gifting,” a Burning Man term for bartering with other partiers. This abhorrence of capitalism does not, however, apply to the entrance fee—tickets to Burning Man cost more than $350.

For most people, the best part of Burning Man is the art: burners, as attendees refer to themselves, sometimes spend the entire year building installations to bring to the festival, from refurbished steam locomotives and giant robots to full-size replicas of Victorian houses on wheels. But while it’s amazing to see, for example, a large-scale stroboscopic zoetrope sitting in the middle of the Nevada desert, the experience is a little less fun when you’re waiting in line for the communal toilet under the blistering midday sun.

That’s the other thing about Black Rock City: its weather. During the day, thermometers regularly reach one hundred degrees; dehydration and heat exhaustion are common problems. But when the sun sets, the temperature can plummet fifty degrees, and it’s not uncommon for predawn temperatures to approach freezing. Frequent wind storms send seventy-five-mile-per-hour gusts whipping across the desert, stirring up so much dust that festival organizers recommend packing masks and goggles to use during whiteouts. And then there’s the dust itself. Highly alkaline, it can give you what’s known as playa foot—a malady unique to the Black Rock Desert that is, in essence, a chemical burn.

Burning Man bills itself as being “radically inclusive,” meaning that anyone and everyone is encouraged to attend (it’s also “radically participatory,” which tends to lead to a lot of drug use). This worked well when the festival was small, but now that Black Rock City’s population is larger than most American towns, it’s begun to experience some of the same problems as a regular metropolitan area, like bike theft, litter, sexual harassment, and even arson—during a lunar eclipse in 2007, several people were nearly killed when someone set fire to the Man five days ahead of time. (The accused suspect was the same man who, several years earlier, admitted to outfitting the sculpture with a giant pair of balls.) The Web site suggests not accepting open drinks from people you don’t know, and warns that the area may be policed by undercover officers using night vision goggles to detect illegal drug trafficking, though the red eyes and vacant stares of many Burning Man participants suggest that this threat is not taken seriously.

There are also rules specific to Burning Man: “Do NOT burn other people’s property!” says one. “Do not bring large public swimming pools or public showers,” says another. And then there’s my favorite: “Defecation on the playa is in violation of the law”—a regulation, it’s worth noting, that wouldn’t exist without good cause.

The Man

Keith Pomakis/Wikipedia Commons

JENNIFER KAHN

Burning Man

T

he year I attended, there were a series of disasters, the most notable being when one of the Man’s giant, mechanically-controlled arms got stuck mid-rise during the finale, with the result that it shot fireworks into the crowd rather than into the sky. That was also the year that a woman, presumably high, fell out of and was then fatally run over by her own Art Car.

There were dramatic events, but really, even without the bleeding and the screaming, the place is awful: a parched desert squat with the population density of a refugee camp, but with more noise—the ceaseless battering of amplified techno music—and less hygiene. I mostly hid in the bookmobile, where, on one particularly hot afternoon, a naked man offered me a filthy banana pancake, macerated after being clutched in his bare sweaty hand. Having been in actual refugee camps, I will say that Burning Man made those look like Tanglewood.

JENNIFER KAHN

is a contributing editor to

Wired

magazine and contributor to

The Best American Science Writing 2009.

V

acations often take place around the water, so it’s tempting to think that a pig lagoon might be a combination of two great things: a swimming hole and BLTs. In fact, what could be better?

If only. As the receptacle for all the waste generated by a modern pig farm, pig lagoons are filled not with water but with shit—and not just shit but everything else that falls through the grates of the pigs’ cages. Blood, afterbirths, dead piglets—they all find their way into the lagoons, which, thanks to blood and bacterial interactions, are not brown but pink.

Lagoons can cover an area of up to 120,000 square feet and reach depths of about three stories. (The average pig produces three times as much feces as your average human, and we slaughter tens of million of pigs in the United States each year—you do the math.) The result is massive stagnant pools of waste contaminated with antibiotics, heavy metals, salmonella, giardia, cyanide, and everything else that passes through the pigs. Unlike most human waste, this sewage is never treated.

Occasionally the lagoons’ polyethylene liners rip. If too much waste seeps under the liners and ferments, the ensuing gas pocket can rise up in the middle of the lagoon like a giant pimple, pushing pig sewage out into the surrounding land. Of course, the farmers are

already

putting it on the land—there’s so much waste that a common way of reducing the lagoons’ volumes is to spray the liquid onto fields as a fertilizer, or sometimes even to pump it directly into the air in hopes that some will evaporate. The resulting pig vapor contains gases like ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, and when inhaled can lead to bronchitis, asthma, nosebleeds, brain damage, seizures, and even death.

But inhalation is nothing compared to the ultimate risk—falling into a lagoon. Consider what happened when a worker in Michigan accidentally toppled in: “His fifteen-year-old nephew dived in to save him but was overcome, the worker’s cousin went in to save the teenager but was overcome, the worker’s older brother dived into save them but was overcome, and then the worker’s father dived in,” wrote Jeff Tietz in

Rolling Stone

. “They all died in pig shit.” It’s hard to think of a more horrible way to go.

W

hile beautiful, the Indian town of Sohra is home to two seemingly contradictory phenomena: it is one of the world’s wettest places, and yet every year, it suffers from drought.

Located almost five thousand feet above sea level, it gets hit full force by the Bay of Bengal arm of the Indian Summer Monsoon, which drops an average of about 450 inches of rain per year, much of which falls during the morning. But thanks to Sohra’s high elevation and deforestation, the water doesn’t stick around—it runs off to the plains of Bangladesh, taking with it a healthy amount of soil and leaving Sohra’s residents with a scarcity of potable water. Adding to the problem: the town has no reservoirs. Instead, when it rains, it pours—and when it stops, there’s nothing safe to drink.

I

will forgive you if, driving along Interstate 10 in Arizona, you stop to see the Thing. How could you not? Much like the Winchester Mystery House (see p. 20), billboards for the Thing—some 247 of them—advertise its existence for miles in each direction.

MYSTERY OF THE DESERT,

they tease.

WHAT IS IT?

Whatever it is, it only costs a dollar—and besides, it’s the only rest stop for miles.

But before you plan a family vacation around the Thing, let’s clarify what you’ll see. After you walk through a cave-like entrance in the gift shop, a path of yellow footprints leads you through two metal sheds, each filled with antiques and art of dubious quality and authenticity. In addition to a large caged display of wooden figures being tortured, the first shed is home to a car carrying several grumpy-looking plastic men.

1937 rolls-royce,

a yellow sign above it announces.

THIS ANTIQUE CAR WAS BELIEVED TO HAVE BEEN USED BY ADOLF HITLER . . . THE THING IS, IT

CAN’T BE PROVED.

The second shed is filled with objects of such supposed value that the designers of the Thing arranged them on scraps of polyester carpet in glass-faced plywood boxes. Among them: a so-called “ancient” churn dating all the way back to eighteenth-century Kentucky, an old grocery scale, and a sculpture of cows having sex.

Resist the urge to linger. The third shed is the home of the legendary Thing, housed in a white cinderblock box below a final yellow sign—and it’d be a bad idea to allow your excitement to build up for too long.

So what is it? An alien? A live dinosaur? No, my friends. The Thing is a desiccated mummy, holding another baby “thing” in its arms, its nether regions covered by an oversize hat. No further explanation is provided.

Believers point to the Thing’s shriveled face and exposed rib as proof that it’s a real mummy. But when the Phoenix National Public Radio station KJZZ did an investigation into its origins, it discovered that the Thing might actually be the work of a man named Homer Tate, a former miner and farmer who found a second career in creating props for sideshows. Using papier-mâché and dead animal parts, he spent his retirement crafting curiosities like devil babies and shrunken heads, which he advertised as “a wonderful window attraction to make your mother-in-law want to go home.” Regardless of who’s looking at it, the Thing is likely to have the same effect.

Colin Gregory Palmer/Wikipedia Commons