Catherine the Great (42 page)

Read Catherine the Great Online

Authors: Simon Dixon

The caricature in this French version of ‘The Imperial Stride’, first published in London on 12 April 1791 NS, was the sort of salacious image that corrupted Catherine’s reputation among her 19th-century male successors.

‘L’Enjambée impériale’, French cartoon of 1791

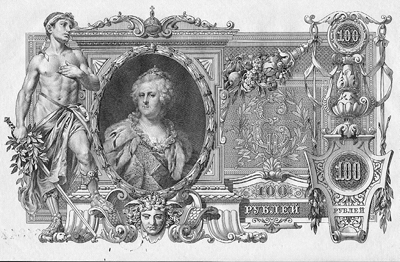

Under Russia’s last tsar, Nicholas II, it was left to the beholder to imagine the relationship between the bronzed youth and the statuesque empress represented by Lampi’s portrait of 1794. Pride of place on the 500-rouble note went to Peter the Great.

100 rouble note of 1910

THE SEARCH FOR EMOTIONAL STABILITY 1776–1784

A

fter her accession to the throne, Catherine spent all too little time at Oranienbaum. But had she ever gazed up from the bed in the Damask Room, she would have seen on the ceiling a painting that perfectly encapsulated the tutelary relationship she strove to establish with each of her favourites.

Urania teaching a youth

, by the Venetian artist Domenico Maggiotto, portrayed a bare-breasted goddess looking down at a virile young man who returns her gaze in simple trust.

1

Leonine, earnest and not very bright, Grigory Orlov had fitted the mould to perfection. ‘The apprehension of the Empress is extremely quick,’ Lord Cathcart observed in 1770, ‘that of Mr. Orloff rather slow, but very capable of judging well upon a single proposition, though not of combining many different ideas.’

2

Horace Walpole was typically franker: ‘Orlow talks an infinite deal of nonsense,’ he remarked during Grigory’s visit to London in 1775, ‘but parts are not necessary to a royal favourite or to an assassin.’

3

Potëmkin, by contrast, demanded to be treated not as a pupil, but as an equal, and it made for heated arguments between them in the spring of 1776. ‘Sometimes,’ Catherine complained, ‘to listen to you speak one might think that I was a monster with every possible fault, and especially that of being beastly.’ It upset her that he resented her other friends, and flounced off in a temper when she refused to listen: ‘We quarrel about power, not about love. That’s the truth of it.’

4

Potëmkin, however, had reason to be unnerved. As a sign of Catherine’s wavering affections, Rumyantsev’s protégé Peter Zavadovsky, who had worked with her on the Provincial Reform, had been promoted Adjutant General on 2 January. This was the favourite’s office, still indelibly associated with Grigory Orlov.

Later that month, Orlov himself unexpectedly returned to Russia, where he promptly fell sick, creating a complicated love triangle in which only Catherine herself can have felt fully at ease. A British diplomat reported that ‘two visits, which the Empress made to the Prince during his illness, caused a very warm altercation between her and the favourite’. Amidst rumours that he had poisoned Orlov, Potëmkin’s downfall was widely predicted, although some acknowledged that this arose ‘rather from its being universally wished, than from any actual symptoms’.

5

Meanwhile, Catherine firmly resisted his attempts to persuade her to remove Zavadovsky. Quite apart from the ‘injustice and persecution’ the dismissal would inflict on ‘an innocent man’, there was her own reputation to consider: ‘If I fulfil this request, my glory will suffer in every possible way.’

6

Instead, her affair with Zavadovsky was publicly confirmed when he was promoted major general and granted 20,000 roubles and 1000 serfs on 28 June, the fourteenth anniversary of the empress’s accession. In an attempt to appease Potëmkin, she appealed to his vanity by presenting him with the Anichkov Palace and 100,000 roubles to decorate it as he pleased. Most of all, however, she appealed to his conscience, reassuring him that even as her passion had cooled, her friendship remained unquestioned: ‘I dare say that there is no more faithful friend than me. But what is friendship? Mutual trust, I have always thought. For my part, it is total.’

7

There is no reason to think this insincere, but she had meant it just as much when she insisted in an earlier note that ‘the first sign of loyalty is obedience’.

8

True equality remained beyond reach in any relationship with an absolute monarch.

Such rapid changes of scene in the empress’s bedchamber prompted persistent rumours in the autumn of 1776 that she had taken yet another lover. Rumyantsev’s name was mentioned. ‘The leading actor of the German comedy is also spoken of,’ noted the venomous French chargé, the chevalier de Corberon: ‘It wouldn’t be surprising, but I doubt it.’

9

In the event, Zavadovsky was to remain in place until May 1777, a month before Orlov finally married his teenage cousin, Elizabeth Zinovyev. While Catherine bombarded ‘Petrushinka’ with passionate billets-doux, the stolid Ukrainian struggled to keep up his working relationship with her, sulking that she had so little time to spend on him. Increasingly conscious that Icarus was an impossible part to play, Zavadovsky discovered that politics was a topic best avoided: ‘If you had thought as much about despotism as I have,’ Catherine warned him, ‘you would not mention it much.’ Soon she was urging him to exchange his insecurity for trust and playfulness: ‘all this feeds love, which without amusement is dead, like faith without kind deeds’.

10

In the

end, it was he who tearfully begged the empress to release him from his misery. As Catherine told Potëmkin, ‘the whole conversation lasted less than five minutes’.

11

Zavadovsky would soon return to a long career at Court, forgiven and befriended like all her former lovers. For the moment, however, he retired smarting to his Ukrainian estate at Lyalichi (later rechristened Ekaterinindar–‘Catherine’s Gift’).

12

‘Amid hope, amid passion full of feelings, my fortunate lot has been broken, like the wind, like a dream which one cannot halt; [her] love for me has vanished.’

13

No sooner had Zavadovsky faded from the scene than a more colourful lover emerged to take his place. This was Potëmkin’s Serbian-born adjutant, Semën Zorich, a swarthy hussar sixteen years younger than Catherine. ‘What a funny creature you have introduced to me!’

14

Having been imprisoned by the Turks after distinguishing himself in action, Zorich seemed less likely than Zavadovsky to suffer from hypochondria. Yet it was no easier for him to cope with the mercurial presence of his patron, who remained the guiding influence in the empress’s life.

15

In May 1778, when Potëmkin humiliated him by presenting a handsome young officer to Catherine on her way to the theatre at Tsarskoye Selo, Zorich could no longer control himself. ‘As soon as Her Imperial Majesty was gone, he fell upon Potemkin in a very violent manner, made use of the strongest expressions of abuse, and insisted on his fighting him.’ Irritated by such a ‘fuss about nothing’, Catherine forced the rivals to shake hands over dinner in St Petersburg, but it was only a temporary rapprochement. ‘Potemkin is determined to have him dismissed,’ reported the recently arrived British ambassador, James Harris, ‘and Zoritz is determined to cut the throat of his successor. Judge of the tenour of the whole Court from this anecdote.’

16

Insensitive to the anguish the empress suffered in her search for a stable, loving relationship–she blamed her recurrent headaches on her recent bout of ‘legislomania’–Harris regarded the ‘scene of dissipation and inattention’ presented by the Court of St Petersburg as the inevitable consequence of unnatural female rule. ‘Age does not deaden the passions, they rather quicken with years: and on a closer approach I find report had magnified the eminent qualities, and diminished the foibles, of one of the greatest ladies in Europe.’

17

Two years later, after Catherine had exchanged the favours of Zorich’s unfaithful successor, Ivan Rimsky-Korsakov, for those of another strapping young guards officer, Alexander Lanskoy, Corberon came to much the same conclusion:

If this sovereign were led, as she could be, by a man of genius, the greatest and

best things might be achieved: but this man is not to be found, and by deluding each of her favourites, doing away with them and renewing them one by one, this woman’s successive weaknesses become innumerable and their consequences appalling. With the greatest of visions and the best of intentions, Catherine is destroying her country through her morals, ruining it by her expenditure, and will end up being judged a weak and romantic woman.

18

Generally the preserve of foreigners, and provoked most often by the failure of a particular ambassador’s diplomacy at St Petersburg, such verdicts owed more to stereotypical assumptions about female rule than to the realities of Catherine’s reign. The political impact of her sex was felt less in her relationship with her favourites than in her treatment of her two grandsons. They were not, however, to be born in the way that she had originally anticipated when the pregnant Natalia was rushed back from Moscow in the summer of 1775. The grand duchess went into labour early in the morning of 10 April 1776, at the height of the crisis between Catherine and Potëmkin. At first there seemed no reason to panic, but when it emerged that the birth canal was too narrow–‘four fingers wide,’ as the watching empress subsequently described it to Frau Bielke, ‘when the baby’s shoulders measured eight’–the midwife left Natalia to writhe in agony for forty-eight hours before calling a surgeon. The unborn child, a large boy, may already have been dead before forceps were used in a vain attempt to save his mother. The cause of the obstruction, a deformation of her spine, was revealed only at the autopsy. Natalia died on 15 April, leaving Paul inconsolable for three days. Even the annual cannon salute to herald the breaking of the ice on the Neva was cancelled as a mark of respect.

19

Dressed ‘very richly in white satin’, with her dead infant at her feet, the grand duchess lay in state at the Alexander Nevsky monastery, where mourners ‘might go and see them, walk up to the coffin, kiss her hand, and then walk round on the other side, but were not suffered to stop, and were obliged to go out again immediately’.

20

Corberon, who blamed Catherine for Natalia’s negligent treatment, noted that she ‘gave the impression of crying’ at the funeral. ‘But I give no credence to her tears: her heart is too dry.’

21

The empress certainly did not linger over her disappointment. As she explained to Voltaire on 25 June: ‘We are currently very busy recouping our losses.’

22

That meant finding a new wife for Paul and there was only one serious candidate: the sixteen-year-old Princess Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg, passed over in 1773

only because she was too young. Ruthless in a crisis, Catherine bought off her existing fiancé Prince Ludwig of Hesse-Darmstadt–‘I never want to see him again,’ she told Grimm–and cunningly soured Paul’s memory of Natalia by revealing her dalliance with Andrey Razumovsky. While Field Marshal Rumyantsev and Prince Henry of Prussia, visiting St Petersburg for the second time, escorted Paul to Berlin for an audience with his hero, Frederick the Great, the empress made arrangements to welcome Sophia to Russia.

23

Having ordered twelve dresses and plenty of Dutch bedlinen, she turned her attentions to the apartments in the Winter Palace, marking out the position of new stoves on the plans and dictating a revised colour scheme for the furnishings: pink and white for the bedroom, with columns of blue glass; blue and gold for the state bedroom, with a new

lit de parade

and a drawing of Raphael’s loggias in the Vatican ‘which I will give you’; cushions for the sofa in the sitting room ‘in gold fabric which I shall supply’. All the rooms were to be hung with tapestries of a specified colour and type, and ‘the second ante-chamber should be decorated in stucco or artificial marble with ornaments as pretty as they are rich’.

24

When Paul returned with his new consort at the end of August 1776, barely four months after the death of his first wife, Catherine promptly declared herself ‘crazy’ about a girl who seemed to have everything Natalia had lacked. ‘She is exactly what I had hoped for: the figure of a nymph; the colour of lilies and roses; the finest complexion in the world; tall and broad-shouldered, yet slight.’

25

Whereas Natalia’s progress in the Russian language had been maddeningly slow, Sophia had already begun to master the Cyrillic alphabet in Berlin. Catherine sent a tutor to ‘lessen the task of learning’ on the journey.

26

She need not have worried: re-baptised Grand Duchess Maria Fëdorovna on her conversion to Orthodoxy, Sophia was to prove the most dutiful of consorts. When the empress led the couple to the altar on 26 September, Grigory Orlov held a crown above Paul’s head after the Orthodox custom. Betskoy, now in his seventies, performed the same service for the bride, his hand trembling with the effort. Why had this honour been granted to such a grizzled courtier? ‘Because bastards are lucky,’ grumbled Corberon, who left the ceremony early finding the crowded chapel uncomfortably warm. Dinner was more agreeable, and much the same in form as Catherine’s own wedding feast thirty-one years earlier. Seated between bride and groom, she dined under a canopy with Alexander and Lev Naryshkin in attendance, facing four tables for statesmen of the first four ranks and their wives:

The gallery above was packed with people and occupied by the orchestra, to

whom no one listened. The famous Nolly [the violinist, Antonio Lolli, who had given four public concerts to great acclaim in the spring] played well to no purpose amidst this brouhaha and the fanfare that followed the toast to Her Imperial Majesty. The tables were narrow and served

en filet

; they were placed underneath the orange trees, which poked their rounded heads out over the guests and made a very fine effect.

27

In the tradition established by Peter the Great, there followed ten days of celebrations, including the obligatory firework display and a reprise of the opera

Armida

(‘I saw and heard little because I was talking,’ Corberon confessed, ‘but the music was feeble, so they say, and only one duet gave me pleasure’).

28

For once, such public festivities were not the prelude to personal disaster. Only mildly offended by the tone of Paul’s written instructions urging thrift, regularity and obedience, his spouse devoted herself to the difficult task of pleasing both her husband and the empress.

29

In time, the couple would irritate Catherine with their profligacy and her son’s eye would begin to wander. In the short term, however, his personal life proved noticeably less volatile than hers. As a waspish Harris noted in February 1778, ‘The great duke and duchess live indeed on the best terms, and offer an example they neither receive, nor can get imitated.’

30