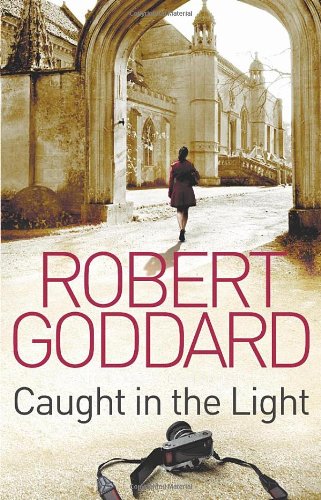

Caught in the Light

Read Caught in the Light Online

Authors: Robert Goddard

Tags: #Psychological, #Thrillers, #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General

Caught in the Light by Robert Goddard

Also by Robert Goddard

PAST CARING

IN PALE BATTALIONS

PAINTING THE DARKNESS

INTO THE BLUE

TAKE NO FAREWELL

HAND IN GLOVE

CLOSED CIRCLE

BORROWED TIME

OUT OF THE SUN

BEYOND RECALL

Robert Goddard

CAUGHT IN THE LIGHT

BANTAM PRESS

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO SYDNEY AUCKLAND

TRANS WORLD PUBLISHERS LTD 61-63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

TRANS WORLD PUBLISHERS (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD 15-25 Helles Avenue, Moorebank, NSW 2170

TRANS WORLD PUBLISHERS (NZ) LTD 3 William Pickering Drive, Albany, Auckland

Published 1998 by Bantam Press a division of Transworld Publishers Ltd

Copyright Robert and Vaunda Goddard 1998

The right of Robert Goddard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All of the characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 0593 042662 (cased) ISBN 0593 043723 (tpb)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Typeset in IIWIS/Linotype Times by Phoenix Typesetting, Ilkley, West Yorkshire.

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk.

PART ONE

COMPOSITION

w Es

rete

Se; ha DC Es Sa

RJ

CHAPTER ONE

I was in Vienna to take photographs. That was generally the reason I was anywhere then. Photographs were more than my livelihood. They were part of my life. The way light fell on a surface never failed to tug at my imagination. The way one picture, a single snapshot, could capture the essence of a time and place, a city, a war, a human being, was embedded in my consciousness. One day, one second, I might close the shutter on the perfect photograph. There was always the chance, so long as there was film in my camera. Finish one; load another; and keep looking, with eyes wide open. That was my code. Had been for a long time.

I'd come close once, in Kuwait at the end of the Gulf War, when some weird aptness in the knotted shape of a smoke plume from a burning oil well made my picture the one newspapers and magazines all over the world suddenly wanted. Brief glory from an even briefer moment. Just luck, really. But they say you make your own the bad as well as the good.

I went freelance after the Gulf, which should have been a clever move and would probably have worked out that way, but for life beyond the lens taking a few wrong turnings. The mid-Nineties weren't quite the string of triumphs I'd foreseen when my defining image of the Gulf madness made it to the cover of Time magazine. That's why I was in Vienna, rather than in Bosnia or Zaire or anywhere even faintly newsworthy. But, still, I was taking photographs. And I was being paid to do it. It didn't sound bad to me.

The assignment was actually a piece of happenstance. I'd done the London shots for a glossy coffee-table picture book: Four Cities in Four Seasons London, Paris, Rome, Vienna, a European co-publishing venture that netted me a juicy commission to hang round moody eyefuls of my home city in spring, summer, autumn and winter. I'd given my own particular slant to daffodils in Hyde Park, heat haze and traffic fumes in Piccadilly, rain-sodden leaves in Berkeley Square and a snow-patched roof scape in we1. I'd also reconciled myself to the best and truest of what I'd delivered being tossed aside. It was, after all, only a picture book. It wasn't meant to challenge anyone's preconceptions or make them see instead of look. And I wasn't Bill Brandt. Any more than my French opposite number was Henri Cartier-Bresson.

It was just after an obliging cold snap over Christmas and New Year that I handed in my London-in-winter batch and got the message that Rudi Schiissner had walked out on the job in Vienna for reasons nobody seemed to think I needed to know about. Rather than call in someone new, they offered me the substitute's role. The Austrian publishers had liked what they'd seen of my stuff, apparently. Besides, I was free, whereas the French and Italian photographers weren't. And I was glad to go. Things at home weren't great. They were a long way from that. A week snapping snowy Vienna didn't have to be dressed up as a compliment to my artistry for me to go like a shot. Anyway, The Third Man had always been one of my favourite films.

They put me up at the Europa, on Neuer Markt, halfway between Stephansdom and the Staatsoper, right in the heart of the old city. I'd last been to Vienna for a long weekend with Faith before we were married: a midsummer tourist scramble round just about every palace and museum in the joint. It had been hot, hectic and none too memorable. I hadn't even taken many photographs. On my own, in a cold hard January, it was going to be different, though. I knew that the moment I climbed off the shuttle bus from the airport and let my eyes and brain absorb the pinky-grey dome of light over the snow-sugared roofs of the city. I was going to enjoy myself here. I was going to take some great pictures.

The first day I didn't even try. I rode the trams round the Ringstrasse, getting on and off as I pleased to sample the moods of the place. The weather was set, frozen like the vast baroque remnants of the redundant empire that had laid the city out. I hadn't seen what Schiissner had done with spring, summer and autumn. I hadn't wanted to. This was going to be my Vienna, not his. And it was going to give itself to me. I just had to let it come. A photograph is a moment. But you have to wait for the moment to arrive. So I bided my time and looked and looked until I could see clearly. And then I was ready.

Next morning, I was out at dawn. Snow flurries overnight meant Stephansplatz would be virginally white as well as virtually deserted. I hadn't figured out how to cope with the cathedral in one shot. Its spire stretched like a giraffe's neck into the silver-grey sky, but at ground level it was elephantine, squatting massively in the centre of the city. Probably there was no way to do it. I'd have to settle for something partial. In that weather, at that time, it could still be magical.

But, then, there's always been something magical about photography. It certainly seemed that way to the Victorian pioneers, before the chemistry of it was properly understood. Pictures develop and strengthen and hold by an agency of their own. You can stand, as Fox Talbot did, in a darkened room and watch a blank sheet of paper become a photograph. And even when you know why it happens you don't lose the sense of its mystery. That stays with you for ever.

Perhaps that's why what happened at Stephansplatz that morning failed in some strange way to surprise me. I'd brought the Hasselblad, but I didn't take a tripod, though technically I should have. I'd always shied clear of accessories, arguing that all you needed to do the job were a good pair of eyes and a decent camera. Plus spontaneity, of course, which you don't get fiddling with tripod legs. I just prowled round the square, looking for the right angle, for some way to give scale as well as atmosphere to the scene. I backed off to the north side, where there was some shelter from the wind, and took a decent shot of the snow slashing across the dark flank of the cathedral. But Schiissner could have managed that. I was looking for something more distinctive, something that would carry my own grace note.

I didn't find it. It found me. With my eye to the camera, I tracked across to the blurred reflection of the cathedral's west front in the glass facade of the Haas-Haus, then slowly down and back until the curve of Kartnerstrasse was an empty white arena beyond the black prow of medieval buttressing, with a shop sign gleaming like a golden snowflake in the distance. Then, just as I steadied the camera, a figure stepped into view round the southern side of the cathedral, red coat buttoned up against the chill, and I had a piece of composition you'd die for. I pressed the shutter release and thanked my stars.

The figure was a woman, dressed in boots, overcoat, gloves, scarf and fur-trimmed hat. I'd have expected her to hurry across the square, head bowed. Instead, she stopped, turned and looked at me as I lowered the camera, then walked towards me. She was frowning, I saw as she approached. She almost seemed to be angry, her dark eyes seeking and challenging my gaze. My first impression was of a pale high-cheeked face framed by the soft black brim of the hat, of eyes that could see as far as they needed to and quite possibly through whatever stood in their way.

"Did you just take my photograph?" she said. The voice was English, unaccented, surprisingly deep.

"You were in the photograph I took," I replied. "It's not quite the same thing."

"It is to me."

"Is there a problem?"

"I don't like having my picture taken." Her nose was broad and flat, almost as if it had once been broken. Somehow that made her more striking still. That and the aggression in her eyes which camera-shyness didn't seem to me to go anywhere near explaining. "Especially not by somebody I don't know."

"That must be difficult for you. I expect you get a lot of requests."

"Funny," she said, looking me up and down. "I thought I'd be safe in Vienna from smart-arse Londoners."

"In January, at dawn." I glanced round the square and nodded. "It was a good bet."

There was a moment's silence, when the only sound was the wind mewling round the cathedral and flapping the camera-strap against the collar of my coat. She should have walked away then, or

I should. But neither of us moved. Incongruity turned towards fascination, and I realized I was no longer sure how this would end.

"It'll be a great picture," I said neutrally.

"What makes you think so?"

"I'm a professional. Trust me."

"Do I have a choice?"

"About the picture? Not really. About breakfast? Well, that's a different matter. You can have it with your husband back at your hotel. Or with me at the Cafe Griensteidl. It's on Michaelerplatz. Maybe you know it."

"Better than you know me, that's for certain."

"You said you didn't like having your picture taken by a stranger. This way I wouldn't be one, would I? Not any more."

"What about your wife? Won't she be expecting you?"

"She's not with me this trip."

"And my husband's not with me. That's how I can be sure of breakfasting alone."

"Please yourself."

"I will, thank you." And with that she did move, round on her heel and smartly away across the square.

I watched her until she'd vanished down the street beside the Haas-Haus, and wondered as soon as she was out of sight why in hell's name I'd behaved as I had. Though she wouldn't know it, it was actually way out of character. For a moment I'd very much wanted not to let our encounter fizzle into nothing beyond a figure in red in the background of a photograph. I'd wanted that with an acuteness I couldn't fathom. It wasn't just disquieting, it was positively eerie. As if I hadn't any idea of what was really going on in my head.

I tried to shrug the sensation off as I made my way down Kartnerstrasse to the Opera House and took some speculative shots of its snow-hazed bulk from various vantage points. But I was cold now and oddly dispirited. I carried on round to Heldenplatz and managed some perspective views of its wide-open arctic spaces. Then I gave up and retreated to the Griensteidl.

And there she was, waiting for me. She was at a table near the far end of the cafe, so tucked away that I didn't see her until I went to grab a newspaper from the rack and recognized her coat and hat on the nearby stand. Then I glanced round and saw her, watching me quite calmly from a distant table.

"You did know the place, then," I said as I joined her.

"I know less than I pretend." The anger was gone from her eyes, but their intensity was undimmed. Her hair was short, expertly cropped in some fashionable bob, and an engagement ring sparkled beside the wedding ring on her left hand as she trailed it round her coffee cup. "Like you, I imagine."

"Why do I get the feeling that you are like me in lots of ways?"

"I don't know. But I do know what you mean."

"I'm sorry if I... said anything stupid back there."

"Why be sorry? If you'd been more polite maybe I wouldn't be here now."

"I usually am, you know. Polite."

"Promise me you won't be ... with me."

"All right. That's easy."

"No, it isn't. Polite means dishonest. Impolite means honest. And honest isn't easy."

The waiter came over and I ordered coffee and a croissant. The uncertainty was delicious now. Just what were we talking about?

"My name's Marian Esguard."

"Esguard? That's unusual."

"My husband's an unusual man."

"He seems a negligent one to me."

"You don't know him. And that's good. That's actually great. I can't remember when I last talked this much to somebody who didn't know him."