Challenger Deep (11 page)

Authors: Neal Shusterman

What I had once thought were rats on the ship’s deck are not rats at all. Although I think I’d prefer it if they were.

“They’re a nuisance,” Carlyle tells me, as he does his best to poke them out of corners and wash them from the deck. They run from his soapy water. They don’t like being wet, or for that matter clean. “Just when you think you’ve got a handle on ’em, more of ’em show up on deck.”

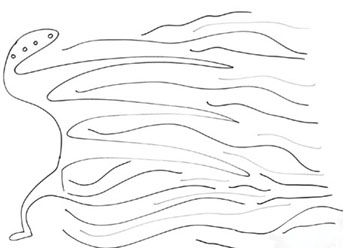

Some ships are infested with rodents. Others cockroaches. Ours has an infestation of free-range brains. The smallest are the size of a walnut, the largest are the size of a fist.

“The damn things escape from sailors’ heads when they’re asleep, or when they’re not paying attention, and go feral.” Carlyle pushes his mop toward a cowering batch of them, and they skitter away on purple little dendrite legs.

“When the day comes to do the dive,” Carlyle tells me, “I gotta make sure there’s not a single brain on deck to foul things up.”

“If they’re brains from the crew, why are they so small?” I ask.

Carlyle sighs sadly. “Either they didn’t use ’em and they atrophied—or they used them too much, and they burned out.” He shakes his head. “Such a waste.”

He dips his mop into his bucket of soapy water and sloshes it into dark corners, flushing the hapless brains out from their hiding places, and washing them out of the ship’s drainage holes into the sea.

He finds a small one clinging to the strands of his mop and he bangs the mop against the rail to dislodge it. “There’s no end to them. But it’s my job to get ’em off the ship before they breed.”

“So . . . what happens to the brainless sailors?” I ask.

“Oh, the captain finds something to fill their heads with, and then sends them on their merry way.”

But somehow it doesn’t sound too merry to me.

It’s the middle of the night. I stand above Calliope at the tip of the bow, and I’m filled with a nasty kind of anticipation. Like the feeling you get five minutes before you realize you’re going to throw up.

There’s a storm on the horizon. Lightning illuminates the distant clouds in erratic bursts, but it’s still too far away to hear the thunder. The sea is too rough for me to drop down into her arms tonight. She has to shout over the roar of the sea to be heard.

“The captain is not entirely wrong to think me magical,” she confides. “I see things no one else does.”

“Things in the sea?” I ask. “Things beneath the waves?”

“No. It’s toward the horizon that I cast my eyes. I see the future in the stars that ride the horizon. Not just one future but all possible futures at once, and I don’t know which one is true. It’s a curse to see all that

might

happen but never know what

will

.”

“How can you see anything in the stars?” I ask her. “The stars are all wrong.”

“No,” she tells me. “The stars are right. It’s everything else that’s wrong.”

Max and Shelby don’t come over anymore for our game-creation sessions. Max doesn’t come at all even though my house has been like a second home to him. He even avoids me in school.

Shelby, on the other hand, makes an effort at conversation in school, but I doubt her motives. If she really wanted to talk to me it wouldn’t be so forced. What is she really up to? What is she saying to Max about me when I’m not there? I’m sure they’ve gotten another artist for their game. They’ll blindside me with it any minute. Or maybe they won’t tell me at all.

Shelby corners me for a conversation. She tries to make small talk. Shelby is more about talking than listening, which is usually fine, but lately I haven’t been a good listener. Mostly I nod when I think it’s appropriate, and if a response is required I usually say, “I’m sorry, what was that?”

But this time Shelby isn’t taking any of it. She sits me down in the cafeteria, forcing me to look her in the eye.

“Caden, what’s going on with you?”

“That seems to be the question of the month. Maybe it’s what’s

going on with you.”

Then she leans close and gets quiet. “Listen, I know about these things. My brother started getting drunk in tenth grade, and it just about destroyed him. I might have been like him, except that I saw what it did to him.”

I pull away. “I don’t drink, okay? Maybe a beer at a party once in a while, you know, but that’s all. I don’t get drunk.”

“Well, whatever it is you’re doing, you can tell me. I’ll understand. Max will, too—he just doesn’t know how to say it.”

Suddenly all my words come out at Shelby in hard consonants. “I’m fine! I’m not

doing

anything. I don’t smoke crack, I don’t snort Ritalin or suck gas from whipped cream cans, and I don’t shoot up Drano.”

“Okay,” says Shelby, not believing me in the least. “When you feel like talking about it, I’ll be here.”

There was this kid I knew back in the second grade. When he got mad, he would bang his head against the wall or the table—whatever was close by and bangable. The rest of us thought it was funny, so we tried to get him mad at every opportunity, just to see him do it. I was guilty of it, too. See, the teacher moved him around the room, hoping to find a spot where he would be okay. Eventually he got moved next to me. I remember this time I had grabbed his

pencil while he was doing math, and pushed down on it, just hard enough to break the tip. He got mad, but not that mad. He glared at me and went to sharpen his pencil. When he got back I waited a minute, then tugged on his paper so his pencil left a streak across the page. He got mad, but not mad enough. So I waited a minute, then I kicked his desk hard enough to send his math book flying off the table and to the ground. The third time was the charm. He glared at me with crazy eyes and I remember saying to myself that I had really gone too far. Now he’d go nuts on me, and it would be my own fault. But instead he began to bang his head against his desk. Everyone was laughing and the teacher had to wrestle with him to get him to stop.

The thing is, we never saw him as a person, just as an object of comic relief. Then one day I saw him in the playground. He was playing all by himself. He seemed fairly content, and it occurred to me that his odd behavior had left him friendless. So friendless that he didn’t know any better.

I had wanted to go over and play with him, but I was scared. I don’t know of what. Maybe that his head-banging was contagious. Or his friendlessness. I wish I knew where he was today, so I could tell him I understand how it was. And how easy it is to suddenly find yourself alone in the playground.

I have never ditched school. Leaving school without permission gets you detention or worse. I’m not that kind of kid. But what choice do I have now? The signs are there. Everywhere, all around me. I know it’s going to happen. I know it will be bad. I don’t know what it’s going to be or what direction it’s going to come from, but I know it will bring misery and tears and pain. Horrible. Horrible. There are a lot of them now. Kids with evil designs. I pass them in the hall. It started with one, but it spread like a disease. Like a fungus. They send one another secret signals as they pass between classes. They’re plotting—and since I know, I’m a target. The first of many. Or maybe it’s not the kids. Maybe it’s the teachers. There’s no way to know for sure.

But I know things will calm down if I’m not in the middle of it. Whatever they’re planning to do won’t happen if I leave. I can save everyone if I leave.

The bell rings. I bolt from class. I don’t even know what class it was. The teacher was speaking Cirque-ish today. Today, sounds and voices are muffled by a liquid fear so overwhelming I could drown in its waters and no one would ever know, sinking down to the depths of some bottomless trench.

My feet want to take me to my next class by force of habit, but there’s a force more powerful compelling my feet now right out the front entrance of the school, my thoughts racing ahead of me like a man on fire.

“Hey!” yells a teacher, but it’s an incompetent, impotent protest. I’m out of there, and no one can stop me.

I race across the street. Horns blare. They won’t hit me. I bend the cars around my body with my mind. See how the tires squeal? That’s me doing that.

There’s a strip mall catty-corner to the school. Restaurants, pet shop, doughnut place. I am free, but I am not. Because I can feel the acid cloud following me. Something bad. Something bad. Not at school—no, what was I thinking? It was never at school. It was at home! That’s where it’s going to happen. To my mother, or my father, or my sister. A fire will trap them. A sniper will shoot them. A car will lose control and ram into our living room, only it won’t be an accident. Or maybe it will. I can’t be sure, all I can be sure of is that it’s going to happen.

I have to warn them before it’s too late, but when I take out my cell phone, the battery is dead. They drained my battery! They don’t want me warning my family!

I race this way and that, not sure what to do, until I find myself on the corner begging everyone who passes to borrow their cell phone. The looks they give me—dead-eyed gazes—chill me. They ignore me, or hurry past, because maybe they can see the steel spike of terror piercing my skull, driving all the way down into my soul.

My panic has subsided. The unbearable sense that something awful is about to happen has settled, although it hasn’t entirely gone away. My parents don’t know I left school early. The school did send out a robocall about “Kah-den Boosh” missing one or more classes, because the automated voice can’t pronounce my name. I deleted it from voice mail.

I lie on my bed, trying to make sense out of chaos, examining the mystery ashtray that holds the remains of my life.

It’s not like I can control these feelings. It’s not like I mean to think these thoughts. They’re just there, like ugly, unwanted birthday gifts that you can’t give back.

There are thoughts in my head, but they don’t really feel like mine. They’re almost like voices. They tell me things. Today, as I gaze out of my bedroom window, the thought-voices tell me that the people in a passing car want to hurt me. That the neighbor testing his sprinker line isn’t really looking for a leak. The hissing

sprinklers are actually snakes in disguise, and he’s training them to eat all the neighborhood pets—which makes some twisted sense, because I’ve heard him complaining about barking dogs. The thought-voices are entertaining, too, because I never know what they are going to say. Sometimes they make me laugh and people wonder what I’m laughing at, but I don’t want to tell them.

The thought-voices tell me I should do things. “Go rip out the neighbor’s sprinkler heads. Kill the snakes.” But I won’t listen to them. I won’t destroy someone else’s property. I know they’re not really snakes. “You see that plumber who lives down the street,” the thought-voices tell me. “He’s really a terrorist making pipe bombs. Go get in his truck and drive away. Drive it off a cliff.” But I won’t do that either. The thought-voices can say a lot of things but they can’t make me do anything I don’t really want to do. Still, that doesn’t stop them from tormenting me by forcing me to think about doing those terrible things.

“Caden, you’re still awake?”

I look up to see my mom at the door of my room. It’s dark outside. When did that happen? “What time is it?”

“Almost midnight. What are you still doing up?”

“Just thinking about stuff.”

“You’ve been doing that a lot lately.”

I shrug. “A lot of things to think about.”

She turns off the light. “Get some sleep. Whatever’s on your mind, it’ll look clearer in the morning.”

“Yes. Clearer in the morning,” I say, even though I know it will be just as cloudy.

Then she hesitates at the threshold. I wonder if she’ll leave if I pretend I’m asleep, but she doesn’t.

“Your father and I think that maybe it would be a good idea for you to

talk

to someone.”

“I don’t want to talk to anyone.”

“I know. That’s part of the problem. Maybe it will be easier to talk to someone different, though. Not me or your father. Someone new.”

“A shrink?”

“A therapist.”

I don’t look at her. I don’t want to have this conversation. “Yeah, sure, whatever.”

Automobile engines aren’t all that complicated. They look that way when you don’t know much about them—all of those tubes and wires and valves—but mostly the combustion engine hasn’t changed that much since it was invented.

My father’s issues with cars don’t end with plunging rearview mirrors. He basically knows next to nothing about cars. He’s all about math and numbers; cars are just not his thing. Give him a calculator and he can change the world, but whenever the car breaks down, and the mechanic asks him what’s wrong, his response is usually, “It broke.”

The automotive industry loves people like my father, because it means they can make lots of money from repairs that the car may or may not need. It annoys my father no end, but he rationalizes it by saying, “We live in a service economy. We all have to feed it somehow.”