Charles Dickens: A Life (17 page)

Read Charles Dickens: A Life Online

Authors: Claire Tomalin

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Authors

The wedding plans had to be changed when Mrs Macrone insisted that the best man must be a bachelor, and Dickens was obliged to ask Tom Beard instead of Macrone. Shortly before the day he wrote to his uncle Thomas Barrow, wishing he could invite him, and explaining that Barrow’s refusal to have John Dickens under his roof made it impossible; he recalled his own visits to him as a child, and thanked him for his interest and affection.

7

It is clear that the Barrow side of the family was the one he was proud of, and yet he remained loyal to his father, feeling the strain, and unhappy about the division in the family.

His mother arranged the honeymoon lodgings for him, in a cottage belonging to a Mrs Nash in Chalk, a small pretty village on the marshes of north Kent, between Rochester and Gravesend. They would not have much more than a week there, and he would be working on

Pickwick

during that time. On 2 April a simple ceremony at St Luke’s Church in Chelsea married Charles and Catherine in the presence of their immediate families, the only other guests being Tom Beard as best man and John Macrone. After a wedding breakfast at the Hogarths’, the bride and groom set off for Kent, a journey of about two hours by public coach. Dickens wanted to show Catherine the country of his childhood and no doubt hoped to walk with her to favourite spots – Cobham Woods, Gad’s Hill, Rochester – in the April sunshine. Catherine was never a great walker, while his idea of enjoyment was to stride far and fast across country, and here perhaps the pattern of their life was set, since he was also obliged to work at

Pickwick

during their few days away. Writing was necessarily his primary occupation, and hers must be to please him as best she could within the limitations of her energy: writing desk and walking boots for him, sofa and domesticity for her.

8

In Dickens’s novels young women meant to be lovable tend to be small, pretty, timid, fluttering and often suffering at the hands of their official protectors, like Little Nell and Florence Dombey. Ruth Pinch (in

Martin Chuzzlewit

) is a good housekeeper and cook, has been a governess, and sings delightfully for her brother and his friend, but the symptoms of her reciprocated love are blushes, tears and a ‘foolish, panting, frightened little heart’. Rose Maylie (in

Oliver Twist

) has no character at all beyond being virtuous and self-sacrificing. Little Em’ly, bold as a child on the beach, becomes another blank victim. Dora has more life, because Dickens can’t resist exaggerating her silliness so that she becomes a figure of high comedy before the pathos sets in. There are more capable young women. Louisa Gradgrind (in

Hard Times

) is no fool, but still a victim, while Sissy Jupe keeps enough of her professional training in the circus to show more strength of character than anyone around her, a working child who sets the middle class to rights. The Marchioness (in

The Old Curiosity Shop

) is another of her type, servant, child of the workhouse, abused and starved, who arises from her basement kitchen, shows strength of character and floors her wicked employers; but Dickens pretty well abandoned her halfway through her history, perhaps because Little Nell had to hold centre stage or because he did not know how to develop the Marchioness. Polly Toodle, Paul Dombey’s wet nurse, is also a young working woman whose instincts are surer than those of her employers. Where does Catherine Hogarth stand among these figures? Clearly, among the blank and blushing innocents, as a virtuous middle-class girl. She had no experience of anything but family life when he met her, and showed little evidence of being interested in anything outside the domestic world. Before their marriage he wrote to her to say how much he looked forward to exchanging solitude for fireside evenings in which her ‘kind looks and gentle manner’ would give him happiness, and assured her that her ‘future advancement and happiness’ was the mainspring of his labours.

9

Kind looks and gentle manner she doubtless had, and a wish to please – what she lacked was the strength of character needed to hold her own against her husband’s powerful will. She was incapable of establishing and defending any values of her own, of making her own safe situation from which she should rule within the home, let alone taking up any other interest. So little of her personality appears in any eyewitness account of the Dickens household that it seems fair to say there was not much more there to describe, and that whatever she brought to the marriage as a twenty-year-old hardly had a chance to develop and mature in the regime set up and ruled over by a husband who seemed omnipresent and always knew himself to be right.

10

Marriage was for him at least a solution to the problem of sex, and for the next twenty-two years they would share a large double bed. ‘A winter’s night has its delight,/Well warmed to bed we go,’ wrote Dickens in a song for his opera this year, only to be told that any mention of bed was objectionable to the public. ‘If the young ladies are especially horrified at the bare notion of anybody’s going to bed,’ he wrote, he would change it, but ‘I will see them d—d before I make any further alteration.’ He added, ‘I am sure … we ought not to emasculate the very spirit of a song to suit boarding-schools.’

11

The bare notion of going to bed pleased him, as it should please a new husband. Catherine was pregnant in the first month of the marriage.

They were soon back in their newly furnished suite of rooms at Furnival’s. She was young to be entering into the responsibilities of a wife in charge of her husband’s domestic life – that is, insofar as Dickens allowed anyone to take charge of any aspect of his life. Her sixteen-year-old younger sister, Mary, was often with them, a trim and cheerful visitor who described Catherine as ‘a most capital housekeeper … happy as the day is long’.

12

Happy and also dealing with the physical changes of pregnancy, and when she felt sick or unsteady Mary gave Charles companionship.

Pickwick

was not selling as briskly as hoped, and the project was struck by disaster at the end of April when Seymour, suffering from depression, shot himself. This could have been enough to sink the whole thing, especially when the replacement artist lacked the right touch. William Makepeace Thackeray, who had skill and ambitions as an illustrator, came to see Dickens with his sketchbook and offered to take on the task, but he was turned down, and the commission went to Hablot K. Browne, a young artist and neighbour, with his studio in Furnival’s Inn. Browne caught the spirit of the work perfectly, called himself ‘Phiz’ to fit ‘Boz’, and made his reputation alongside Dickens.

In May, Dickens agreed with Macrone that he would write a three-volume novel to be called ‘Gabriel Vardon’ – it became

Barnaby Rudge

– and delivered ‘next November’, for a payment of £200. The second volume of the

Sketches

was being prepared, and he still had his full-time job with the

Chronicle

. In June he was kept especially busy reporting a scandalous case in the law courts in which the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, was accused of adultery by the loutish jealous husband of Caroline Norton, the beautiful and gifted granddaughter of Sheridan. The public was of course eagerly interested in this washing of the dirty linen of the upper classes, but Mr Norton failed to produce any evidence and lost his case. Dickens had to move nimbly between the roles of reporter and novelist, and in the same month he was inspired to carry

Pickwick

from its shaky start to popular success as he introduced the character of Sam Weller, Pickwick’s cockney servant.

From this moment sales of the monthly numbers in their pale green wrappers rose steadily and soon spectacularly, and the critics vied with one another to praise it. The appearance of a fresh number of

Pickwick

soon became news, an event, something much more than literature. ‘Boz has got the town by the ear,’ a critic said, and he spoke the truth.

13

Each number sold for a shilling and they were passed from hand to hand, and butchers’ boys were seen reading them in the streets.

14

Judges and politicians, the middle classes and the rich, bought them, read them and applauded; and the ordinary people saw that he was on their side, and they loved him for it. He did not ask them to think but showed them what he wanted them to see and hear. The names of his characters became common currency: Jingle, Sam Weller, Snodgrass and Winkle, Mrs Leo Hunter the cultural hostess with her ‘Ode on an expiring Frog’, the political journalists Slurk and Pott, the drunken medical student Bob Sawyer. It was as though he was able to feed his story directly into the bloodstream of the nation, giving injections of laughter, pathos and melodrama, and making his readers feel he was a personal friend to each of them. Dickens knew he had triumphed, and this sense of a personal link between himself and his public became the most essential element in his development as a writer.

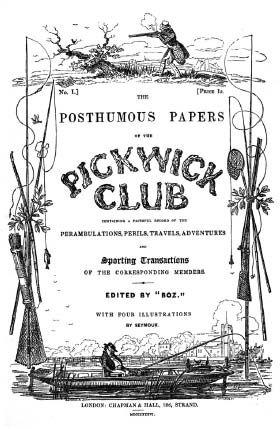

The Pickwick Papers as it first appeared, serialized in green-paper wrappers.

He already had two publishers – Macrone for

Sketches

and Chapman & Hall for

Pickwick

– and in August 1836 he agreed to write a children’s book for a third, Thomas Tegg, for £100. A children’s book could be seen as a special case. Later in the same month, however, he entered into negotiations with a fourth, Richard Bentley, who had been pursuing him for some time. Bentley trumped Macrone with an offer of £400 for the copyright of his next novel. Dickens pushed him up to £500, and Bentley pushed Dickens up to promising two novels. Dickens then sold him the publishing rights in his opera, describing it as ‘Boz’s first play’, which Bentley did indeed publish as a pamphlet. Dickens also agreed to become editor of a monthly magazine for Bentley, what was eventually called

Bentley’s Miscellany

, to which he would contribute something of his own every month, for twenty guineas. This would bring him a further annual income of nearly £500.

15

He now had arrangements with four different publishers, with all of whom he was for the moment on good terms. Macrone was just bringing out the second printing of the

Sketches

. At this point Dickens sensibly asked for time off from the

Chronicle

and was granted five weeks, since things were idle during the summer heat in London. He left with the suggestion that the

Chronicle

should run extracts from

Pickwick

while he was away.

He took Catherine to the village of Petersham in Surrey, between Richmond Park and the Thames, where they put up at the inn and enjoyed the quiet water meadows and leafy walks around Ham House. There they stayed into September, Catherine now halfway through her pregnancy. But even during this holiday he was often obliged to return to London, and rather than go to their empty rooms at Furnival’s he took himself to his parents, currently lodging in Islington.

16

He was working on the opera with Hullah, and preparing for the opening of his farce,

The Strange Gentleman

, on 29 September at the St James’s Theatre, with his friend John Pritt Harley, a well-loved comic actor, playing the lead.

17

It was a success, running for sixty nights, and boxes were offered to friends, family and publishers.

In November, Dickens signed his second agreement with Bentley. He also wrote to John Easthope at the

Chronicle

to tender his resignation; and he informed Macrone he wanted to withdraw from the agreement they had made on 9 May. Easthope was displeased at losing his brilliant reporter, and acrimonious letters were exchanged. The friendship with Macrone was also put under strain. He published the second series of

Sketches by Boz

in December, but things were not the same between them. Dickens was now committed to the following projects: he had to continue

Pickwick

in monthly instalments for another year; he had to provide a few more pieces for the

Sketches

; both his farce and his opera were being published and needed seeing through the press; he had promised a children’s book, ‘Solomon Bell the Raree Showman’, by Christmas; he had to start preparing for his editorship of

Bentley’s

Miscellany

, which began in January and for which he must commission articles and also contribute a sixteen-page piece of his own every month; Chapman & Hall were hoping for a sequel to

Pickwick

; Macrone still wanted ‘Gabriel Vardon’; and Bentley was expecting two novels.

Clearly, this was not a possible programme for one man. For the publishers it was maddening to find him reneging on a promise, as he did to Macrone, to Tegg and then to Bentley. One of the problems for him was that, as his fame grew and he was ever more in demand, he resented having made agreements for lower sums than he could now command. If Dickens is to be believed, each publisher started well and then turned into a villain; but the truth is that, while they were businessmen and drove hard bargains, Dickens was often demonstrably in the wrong in his dealings with them. He realized that selling copyrights had been a mistake: he was understandably aggrieved to think that all his hard work was making them rich while he was sweating and struggling, and he began to think of publishers as men who made profits from his work and failed to reward him as they should. Chapman & Hall kept on good terms with him largely by topping up what they had initially agreed with frequent extra payments. The book for children was quietly dropped. But by the middle of the following year, 1837, there were furious rows. His friend Macrone was now a ‘blackguard’ and a ‘Robber’. Bentley was the next, becoming in due course an ‘infernal, rich, plundering, thundering old Jew’ – a quotation from his own dialogue in

Oliver Twist

.

18