Charles Dickens: A Life (30 page)

Read Charles Dickens: A Life Online

Authors: Claire Tomalin

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Authors

Like many English visitors, they were amazed to find that the sky above Italy could be grey and cloudy even in summer, and it remained so for some time. The house Fletcher had found for them was also a severe disappointment. Dickens said the Villa Bagnerello looked like a pink jail, it was not in Genoa but several miles outside, at Albaro, and it was infested with fleas. Little Katey fell ill and would be nursed by no one but her father. But living was cheap, with excellent white wine at a penny farthing the pint, and he was not obliged to work, could breakfast at 9.30 and make punch with green lemons: ‘I never knew what it was to be lazy before.’

4

The declaration is true and touching: not much leisure had been allowed into his life since the age of twelve. He found that he enjoyed swimming in the sea. He grew a moustache. He rode in and out of Genoa, and walked by day, until in August the heat made night the only time for walking. He found that his immediate neighbour, Monsieur Allertz, was the French Consul at Genoa, a hospitable man of literary tastes, who gave splendid dinners, and introduced him to the French Romantic poet and diplomat Alphonse de Lamartine as he passed through Genoa on his way to Naples. Although at this date Dickens barely spoke French, Lamartine’s wife was English, and the two men were ardent reformers with shared views about prison reform and copyright; they would meet again in Paris in 1847, and a third time in 1855. Other entertainment offered itself at the Teatro Carlo Felice, where he took a private box; the season opened with a dramatization of Balzac’s

Le Père Goriot

, and continued with Bellini’s

La Sonnambula

and Verdi’s new opera

I Lombardi

. He read Tennyson (‘what a great creature he is!’).

5

Yet he was restless, and when Fred came to spend his holidays with them, he travelled to Marseilles to meet him, and they visited Nice before taking the coastal road back into Italy together. Fred was also sporting a moustache, which may have decided Dickens to get rid of his; and, fond as he was of his brother, he was no substitute for his friends.

6

He told Maclise that ‘Losing you and Forster is like losing my arms and legs; and dull and lame I am without you.’

7

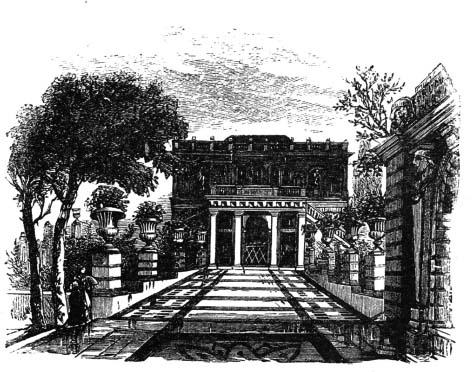

Palazzo Peschiere in Genoa, where Dickens lived with his family in 1844.

He set out to find somewhere better to live, and succeeded in renting the sixteenth-century Palazzo Peschiere, or ‘Palace of the Fishponds’, in the heart of Genoa but with spacious terraced gardens, and set on a height that gave it a view over the surrounding town, the harbour and the sea. They moved at the end of September. It was easily the most magnificent house he ever lived in, and he sent friends enthusiastic accounts of the fifty-foot-high ceiling to the great hall, the patterned stone floors, the frescoes, the bedrooms decorated with nymphs and satyrs, the balconies and terraces, the fountains and sculptures. Here he dreamt of a blue-robed, Madonna-like spirit whom he knew to be Mary Hogarth, and who, as he wept and stretched out his arms to her, asked him to form a wish and recommended the Roman Catholic faith to him. He woke with tears running down his face, roused Catherine to describe the dream and explained its causes to himself: he had been looking at an old altar in the bedroom and hearing convent bells. But in describing it to Forster he wondered whether he should regard it ‘as a dream, or an actual Vision!’

8

Dreams and visions are central in the Christmas book he started on now,

The Chimes

, in which a poor old man, Trotty Veck, is sent visions by the spirits of the bells in the church where he stands every day waiting for work, spirits described as goblins, phantoms or shadows. It is hardly read today, but it was written with red-hot feeling and meant to shame the cruel and canting rich of the 1840s. Like the

Carol

, it looked at the condition of the poor in England, but with a directly political message, attacking the complacency of political economists with Malthusian ideas, magistrates who sentenced suicidal young women to prison or transportation, and landowners who enforced the Game Laws and toasted ‘The Health of the Labourer’ at their agricultural dinners while allowing the labourers to starve. He knew what he was talking about: the magistrate he satirized was an acquaintance, and a smart political economist had attacked him in the

Westminster Review

for failing to inform readers of

A Christmas Carol

as to ‘who went without turkey and punch in order that Bob Cratchit might get them’. In Trotty Veck’s visions he sees his daughter and another young woman driven to prostitution and suicide by poverty, and the young man his daughter loves unjustly sentenced turning to crime; and although Dickens supplied a conventionally happy ending in which Trotty Veck wakes up and finds it was all a dream, readers could see that the visions were showing much of the truth of life for the poor. Modern readers may feel that he was more successful in his mockery of the powerful than in his presentation of the oppressed, but many tears were shed over them at the time.

Forster was so impressed when he read

The Chimes

that he made a secret approach to Napier, editor of the

Edinburgh Review

, telling him that it was ‘in some essential points’ the best thing Dickens had yet written, and asking to review it anonymously before publication. Napier agreed, and Forster wrote a eulogy, saying that ‘Questions are here brought to view, which cannot be dismissed when the book is laid aside. Condition of England questions … Mighty theme for so slight an instrument! but the touch is exquisite, and the tone deeply true … Name this little tale what we will, it is a tragedy in effect.’

9

The piece was a puff, and there were smiles when its authorship got out.

The Chimes

did make something of a political uproar, as was intended, but in the long run it did not approach the popularity of the

Carol

, and Forster himself acknowledged later that it was ‘not one of his [Dickens’s] greater successes’.

10

Whether Dickens knew what Forster had done or not, the shared experience with

The Chimes

brought them still closer. While writing he had missed the streets of London, his usual thinking place, and he posted the first part of the story to Forster, telling him, ‘I would give a hundred pounds (& think it cheap) to see you read it.’

11

Then it came to him that he could make a dash to London in late November, so that he

could

read it with Forster and other friends. The story was finished on 4 November, Dickens suffering from a cold so severe he could hardly see, and shedding tears over his own work.

On 21 November he set off northwards with his courier Roche. They went up the Simplon Pass by moonlight, saw the day break on the summit and sledged through snow dyed rosy red by the rising sun. Then Fribourg, Strasbourg, and a French diligence that got him uncomfortably to Paris in fifty hours. He made such good time that he arrived in England a day earlier than he had expected. He had asked Forster to book him a room in the familiar Piazza Coffee House in Covent Garden, to be near Lincoln’s Inn, and on the evening of 30 November he walked into the public rooms, saw Forster and Maclise sitting by the fire and rushed into their arms. He had eight days in London, and the emotion was kept at a high level among the friends, all bachelors together for a few days, with much weeping, laughing, embracing and sitting up into the small hours.

12

Leech was invited to breakfast to be thanked for his illustrations, and Forster set up a tea party in his rooms for 3 December, at which Dickens read the whole story to a select group of guests – Carlyle, Maclise, Stanfield, a number of radical writers including Douglas Jerrold and the editor and essayist Laman Blanchard, and not forgetting brother Fred.

13

Maclise sent Catherine a sketch of the scene, putting a radiant halo over Dickens’s head, and told her ‘there was not a dry eye in the house … shrieks of laughter … and floods of tears as a relief to them – I do not think that there was ever such a triumphant hour for Charles.’

14

And Dickens wrote to her, ‘If you had seen Maclise last night – undisguisedly sobbing, and crying on the sofa, as I read – you would have felt (as I did) what a thing it is to have Power.’

15

This first experience of power as a reader of his own words was so intense and gratifying that his old interest in performance began to stir in him again. He gave a second reading, and he and Forster talked about putting on plays. Meanwhile three separate dramatizations of

The Chimes

were in preparation for Christmas runs in London.

If he was to reach Genoa for Christmas he had to be on his way again, and on the evening of 8 December he set off. Paris was under snow, and he lingered to spend a few days with Macready, about to play Othello, Hamlet and Macbeth to the French. From Paris he wrote a heartfelt letter to Forster, ‘I would not recall an inch of the way to or from you, if it had been twenty times as long and twenty thousand times as wintry. It was worth any travel – anything! … I swear I wouldn’t have missed that week, that first night of our meeting, that one evening of the reading in your rooms, aye, and the second reading too, for any easily stated or conceived consideration.’

16

The bond between them had been drawn tighter by the visit, and once back in Genoa he moved the friendship into a new phase, for the first time telling Forster something about his young life, with a description of how he had hoped and planned to become an actor; and over the next years he told him more, and gave him a written account of the whole secret story of his childhood, his father’s imprisonment and his work at the blacking factory; then suggested that Forster should become his biographer. He was able to be intimate with Forster as with no other man or woman, and so, scarcely into middle age, he fixed on the idea that this was the one person he trusted to write his life, and never wavered from that decision.

Just as he was writing the letter about his audition, Forster’s brother died suddenly, still in his thirties. Dickens wrote to comfort him. His words read like a further consecration of their friendship. ‘I feel the distance between us now, indeed. I would to Heaven, my dearest friend, that I could remind you in a manner more lively and affectionate than this dull sheet of paper can put on, that you have a Brother left. One bound to you by ties as strong as Nature ever forged. By ties never to be broken, weakened, changed in any way – but to be knotted tighter up, if that be possible, until the same end comes to them as has come to these … I read your heart as if I held it in my hand, this moment.’

17

Meanwhile he had a new interest in Genoa. Among the friends they had made there was a banker, Emile De La Rue, an English-speaking Swiss from Geneva, married for ten years to an English wife, Augusta

née

Granet.

18

They lived in a pretty, high-windowed and comfortable apartment at the top of a Genoese palazzo, up many stairs and across many landings lined with antique busts, and she appeared charming and animated in society; but she was suffering from a nervous disorder – tic douloureux, headaches, insomnia, occasional convulsions and catalepsy – a list of ailments that sound very like those of the nineteenth-century women who turned up a little later in the clinics of Dr Charcot and Dr Freud and were described as suffering from hysteria. Just before Dickens made his November dash to England, De La Rue mentioned his wife’s problems to him, and he responded. He may have said something about his doctor in London, Elliotson, who used mesmerism to deal with cases of this kind, and gone on to say that he had some skill in mesmerism himself. De La Rue was so impressed that, within days of Dicken’s return, he asked him to come over and try his powers on Madame De La Rue. No doubt he was intrigued by the idea of the famous writer attending his wife, and she was willing and pleased with the attention. On 23 December, Dickens began the treatment. It was a highly unusual situation, given that he had no medical training, but he was eager to try what he could do, and the De La Rues were grateful.

Dickens was confident he could do something for Augusta De La Rue and prepared to play the doctor. He believed in Elliotson, was delighted with his own ability to send Catherine and Georgina into trances, and felt that a real patient would give him the chance to do good, and to justify his faith in mesmerism. At that time it was thought of as being some sort of magnetic force, not yet explained or even understood, and Dickens would speculate as to whether the magnetism worked on the nervous system of the patient; but very little was known about the nervous system, and it was found later that the idea of a magnetic force had no basis in fact. It was nevertheless obvious, and remains true, that some people, not necessarily armed with any scientific qualifications, are able to produce behavioural changes in susceptible people. And there is no doubt that something did happen between Dickens and Augusta De La Rue, although it is hard to say what exactly it was.