Charles Dickens: A Life (65 page)

Read Charles Dickens: A Life Online

Authors: Claire Tomalin

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Authors

The bond with Forster was as strong as it had ever been, and he read each number of

Edwin Drood

aloud at his house in Palace Gate as he finished it, and talked over the plot with him. On 21 March, ten days before the first number was published, he read the fourth, and afterwards confided to his friend that, as he walked along Oxford Street earlier, he had once again been unable to read the right side of the names written on the shop fronts. At the end of the month he wrote to him describing a recurrence of severe haemorrhage from his piles which left him shaken: the laudanum he took to help him sleep would have caused constipation, making the piles worse. Still, he was not deterred from leading his active life. On 28 March he signed an agreement with Frederic Chapman and Henry Trollope, son of Anthony and a new partner in Chapman & Hall, covering the copyright of all his books, which was shared equally between himself and the publishers. He celebrated Forster’s birthday with him on 2 April. On 5 April he spoke at the dinner of the Newsvendors’ Benevolent and Provident Institution, warming them up with jokes and urging them to contribute more to their own pension fund. On 6 April he put on court dress and attended a levee at the palace. The next day he held a large reception at Hyde Park Place, at which the violinist Joachim and the pianist Charles Hallé both performed, as well as solo and group singers. He had done nothing so ambitious in the way of entertainment since the days at Tavistock House.

In April, Charley formally took over from Wills at

All the Year Round

. Then, on 2 June, Dickens added a codicil to his will giving Charley the whole of his own share and interest in the magazine, with all its stock and effects.

9

In this way he did the best he could to look after the future of his beloved first-born son, in whom he had once placed such hopes: he would not – could not – now give up on him, in spite of his failures and bankruptcy. Henry continued to do well at Cambridge and could be relied on to make his own way. In May he wrote to his fourth son, Alfred, expressing his ‘unbounded faith’ in his future in Australia, but doubting whether Plorn was taking to life there, and mentioning Sydney’s debts: ‘I fear Sydney is much too far gone for recovery, and I begin to wish that he were honestly dead.’

10

Words so chill they are hard to believe, with which Sydney was cast off as Walter had been when he got into debt, and brother Fred when he became too troublesome, and Catherine when she opposed his will. Once Dickens had drawn a line he was pitiless.

The conflicting elements in his character produced many puzzles and surprises. Why was Charley forgiven for failure and restored to favour, Walter and Sydney not? Because Charley was the child of his youth and first success, perhaps. But all his sons baffled him, and their incapacity frightened him: he saw them as a long line of versions of himself that had come out badly. He resented the fact that they had grown up in comfort and with no conception of the poverty he had worked his way out of, and so he cast them off; yet he was a man whose tenderness of heart showed itself time and time again in his dealings with the poor, the dispossessed, the needy, other people’s children. Again, the lover who longed to take Nelly to America with him could not think of living permanently with her in England, not only because of the inevitable scandal, but also because he was attached to his life at Gad’s Hill, calmly presided over by Georgina, who served him and limited the demands she made on him. There was another life he valued too, with Dolby and at the office, where he could enjoy being a bachelor, dining well, theatre-going and drinking late with men friends. He grumbled about Forster, his dullness, his surrender to middle-class values and conventions, but he could not manage without him, and the words he had written to him in 1838 – that nothing but death should impair ‘the toughness of a bond now so firmly riveted’ – remained true to the end. In his writing too there were conflicts, a touch of ham certainly, but alongside it the dazzling jokes, the Shakespearean characterization, the delicacy and profundity of imagination, the weirdness and brilliance of his descriptive powers.

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

sold well from the start, outstripping

Our Mutual Friend

by 10,000 and reaching 50,000 a number. Dickens, sending pages of manuscript to the printer, put in a note to tell him, ‘The safety of my precious child is my sole care,’ an unexpected image from this most masculine of writers who had never before described his work as his child.

11

Drood

has fascinated readers because it is a murder story left unfinished and unsolved, with touches of exoticism, opium, mesmerism, Thuggee practices,

12

all new departures for him. It also contains haunting and melancholy descriptions of Rochester, the city of his childhood, beautifully rendered; but the mystery is a slight one, the villain less interesting than he promises to be at first, the comedy only moderately funny, the charm a little forced, and the language reads at times like a parody of earlier work. There is a nicely done bad child who throws stones and pronounces cathedral ‘KIN-FREE-DER-EL’, which Dickens may have heard and appreciated in the streets of Rochester; and what was finished – twenty-two chapters, making half of what was intended – is perfectly readable.

Drood

has to be seen in three ways. First, as the unfinished mystery which has received extraordinary attention just because it is a puzzle left by Dickens and offers itself for endless ingenious speculation by those who enjoy thinking up solutions. Secondly, as half a novel which cannot be regarded as a major work, and which has divided opinion sharply even among Dickens’s warmest admirers, from Chesterton’s hailing it as the creation of a dying magician making ‘his last splendid and staggering appearance’ to Gissing’s and Shaw’s dismissal of it as trivial and of no account. And thirdly, as the achievement of a man who is dying and refusing to die, who would not allow illness and failing powers to keep him from exerting his imagination, or to prevent him from writing: and as such it is an astonishing and heroic enterprise.

Until the end of May he was officially based at Hyde Park Place, but often at Wellington Street, and sometimes he escaped to Gad’s, and without doubt to be with Nelly too. Early in February he tells a friend he has been away in the country for two days, in mid-April he says he has been ‘working hard out of town’ over a weekend, and later in the month he mentions ‘a long country walk’ at Gad’s Hill – any or all of these might mean time with her.

13

The death of Maclise brought sorrow although they had scarcely been in touch for years, and he spoke tenderly of him at the Royal Academy dinner on 30 April. It was his last speech and made a great impression. On 2 May he and Mamie dined with his old friend Lavinia Watson and her children, on a visit to London from Rockingham. After this he told one correspondent he was going out of town ‘to get a breath of fresh air’ for two days, and another, ‘I have been (and still am), in attendance on a sick friend at some distance,’ which sounds like Peckham again.

14

On 7 May he read aloud the fifth episode of

Drood

at Forster’s. Now the pain in his foot was stirring again and he began to be ‘dead-lame’ and had to take more laudanum at night. Ouvry was asked to come to his office to transact business and other engagements were cancelled, including his attendance at the State Ball at Buckingham Palace on the 17th, to which Mamie went without him. He managed to dine with the American Ambassador, Motley, and with Disraeli, and took breakfast with Gladstone.

15

On 22 May, Forster dined with him at Hyde Park Place. He had news of the death of another once dear friend, Mark Lemon, and sent Charley to represent him at the funeral. Then on 24 May he somehow got himself to dinner with Lord and Lady Houghton, she being the granddaughter of the Lady Crewe for whom his grandmother had worked as housekeeper: he was invited there to meet the Prince of Wales, who particularly wished to be introduced to him, together with Leopold II, King of Belgium. Dickens was at the dinner and in reasonably good form, but he was unable to go upstairs to the drawing room afterwards.

16

He was also kept busy by his daughters, giving advice and assistance to an amateur group with whom they were putting on a play at the Kensington house of a rich builder, Charles Freake, whose children were their friends. Dickens went there for some rehearsals, and indeed Katey said she was with him constantly in town about this time.

17

There was another dinner with the indefatigably hospitable Lady Molesworth. One guest recalled him as bubbling over with fun, but the young Lady Jeune, who had her only meeting with him at Lady Molesworth’s dinner table, remembered sitting between him and Bulwer, aware that ‘the noise and fatigue of the dinner seemed to distress him [Dickens] very much.’

18

Worse, his lameness was making it more difficult for him to work at his novel: ‘Deprivation of my usual walks is a very serious matter to me, as I cannot work unless I have my constant exercise.’

19

So on 25 May he took himself to Gad’s Hill, ‘obliged to fly for a time from the dinings and other engagements of this London Season, and to take refuge here to get myself into my usual gymnastic condition’ – but ‘circuitously, to get a little change of air on the road’.

20

He remained there until 2 June, sending Fechter a rhapsodic description of the improvements to the house and garden: the conservatory was finished, the rebuilt main staircase had been gilded and brightly painted, and the garden was being managed by a new gardener who had improved the gravel paths and installed forcing houses for melons and cucumbers as well as flowers.

21

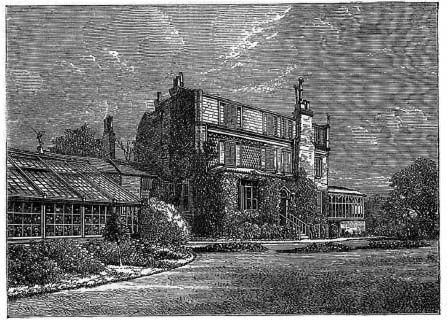

View of the house at Gad’s Hill from the garden at the back, showing the conservatory (

right

) Dickens had built.

He was still resting at Gad’s when the Hyde Park Place house was officially given up, on the last day of May. Then, on Thursday, 2 June, he was back in London, at Wellington Street, where Dolby, making his weekly visit to the office, found him immersed in business and looking strained – depressed, and even tearful, he noted. They had their lunch together, talked of Dolby visiting Gad’s to see the improvements, shook hands, said ‘next week, then’ and parted. That evening he went to the Freakes’ mansion in the Cromwell Road to join his daughters at their theatrical entertainment and acquitted himself well as stage manager, although Charles Collins found him sitting alone behind the scenes afterwards, apparently thinking he was at home – which home, you have to ask.

22

It was a hot night and he went back to Wellington Street to sleep. There Charley found him in the morning, so absorbed in working on

Drood

that he did not answer when spoken to. He remained seemingly oblivious of the presence of his son, and even when he turned in his direction appeared to look through him. So Charley left him without any farewells.

Forster was away in Cornwall, working. Dickens was back at Gad’s in the evening, where Georgina was expecting him. He ordered four more boxes of his usual cigars and, for his painful foot, a ‘voltaic band’, a type of electric chain that had become a fashionable all-purpose cure, recommended to him by the actress Mrs Bancroft and supplied by Isaac Pulvermacher, Medical Battery Maker.

23

Both his daughters came down on Sunday, and after Georgina and Mamie had gone to bed that night he sat up talking with Katey. ‘The lamps in the conservatory were turned down, but the windows that led into it were still open. It was a very warm, quiet night, and there was not a breath of air: the sweet scent of the flowers came in … and my father and I might have been the only creatures alive in the place …’ So Katey sets the scene for her great talk with her father in which she asked his advice – should she take up an offer to go on the stage? He warned her against the idea, telling her she was pretty and might do well, but that she was too sensitive. ‘Although there are nice people on the stage, there are some who would make your hair stand on end. You are clever enough to do something else.’ As they talked on he said he wished he had been ‘a better father – a better man’ and told her things he had never discussed with her before, no doubt concerning the separation from her mother and his relations with Nelly. He also expressed a doubt as to whether he would live to finish

Drood –

‘because you know, my dear child, I have not been strong lately’. He spoke, she said, ‘as though his life was over and there was nothing left’.

24

Katey and Mamie were leaving for town together the next morning. When they came down their father was already working in his chalet in the wilderness – he had ordered his breakfast for 7.30 because he had so much to do, he told the maid – and since he disliked partings they did not think of disturbing him. But, as they sat in the porch waiting for the carriage to take them to the station, Katey felt she wanted to see him again. She hurried through the tunnel under the road to the wilderness, then up the steps to the upper room of the chalet in which he worked. When he saw her he pushed his chair away from the writing table and took her into his arms to kiss her, holding her in an embrace she would never forget.