Charles Dickens: A Life (75 page)

Read Charles Dickens: A Life Online

Authors: Claire Tomalin

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Authors

Henry, the only son to prosper, persuaded his father to let him go to Cambridge and became a lawyer.

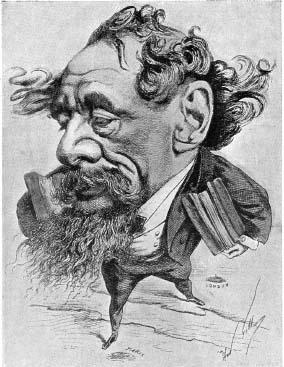

Cartoon showing Dickens crossing the Channel for Paris with books under both arms, published in

L’Eclipse

in 1868, drawn by the French artist André Gill – he took the pseudonym in homage to Gillray – from a photograph by John Watkins.

‘The British Lion in America’, an American cartoon of 1867, elaborates on a photograph by Jeremiah Gurney and shows Dickens wearing a flashy jacket and a lot of jewellery, and with a wine glass.

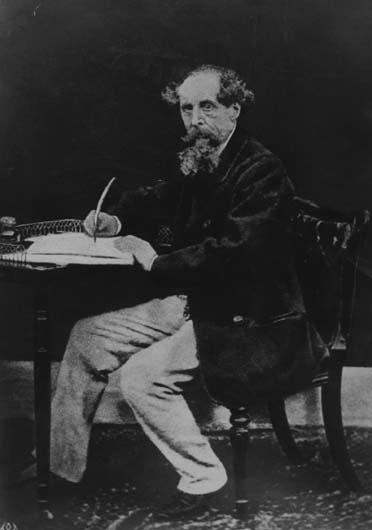

The old lion, grizzled, ravaged, fierce, not giving up. He disliked being photographed but he put up with it, sitting at his desk, quill pen in hand – inimitable as ever.

| ABBREVIATIONS | |

| | |

| AYR | All the Year Round |

| Catherine D | Catherine Dickens |

| D | Charles Dickens |

| F | John Forster |

| GH | Georgina Hogarth |

| HW | Household Words |

| P | The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens (details for each volume can be found in the Select Bibliography) |

1.

Dickens’s words from his account written many years later, ‘Some Recollections of Mortality’,

AYR

, 16 May 1863. Other information from the report on the trial at the Old Bailey printed in

The Times

, 10 Mar. 1840.

2.

D to F, [?15 Jan. 1840],

P

, II, p. 9. Taken from Forster’s

Life of Charles Dickens

, I (London, 1872),

Chapter 13

.

3.

There is a small discrepancy, however: in a letter written at the time he says he could not sleep on the night after the inquest, but in the 1863 account he says he dreamt of the face of the accused girl. ‘Some Recollections of Mortality’,

AYR

, 16 May 1863.

Magdalen Asylums were well intentioned but not pleasant, and Dickens later formed a poor opinion of them when he saw a good many young women who emerged from their care during the 1850s, after he had set up the Home for Homeless Women. He thought they were too punitive in their attitudes, and did not feed the young women properly.

4.

D to Richard Monckton Milnes, 1 Feb. 1840,

P

, II, p. 16.

5.

D to F, [?Jan. 1840],

P

, II, p. 15; D to Mrs Macready, 13 Nov. 1840,

P

, II, p. 150.

6.

Louis Prévost, a linguist who later worked at the British Museum. There are several payments to him from Dickens.

7.

This is John Overs, to whom Dickens devotes a great deal of time and trouble over the years, advising him, helping him to place articles and finding him employment. Overs died at the age of thirty-six in 1844, leaving a wife and six children, whom Dickens continued to assist.

8.

D to Catherine D, 1 Mar. 1840,

P

, II, p. 36; D to Thomas Beard, 1 June 1840,

P

, II, p. 77.

9.

So his daughter Katey said: Gladys Storey,

Dickens and Daughter

(London, 1939), p. 223.

10.

‘A Walk in the Workhouse’,

HW

, 25 May 1850.

11.

D to Jacob Bell, 12 May 1850,

P

, VI, p. 99.

12.

Walter Bagehot in

National Review

, Oct. 1858.

13.

He used the name in printed correspondence in

Bentley’s

Miscellany

, which he edited in 1837 and 1838, and during this period his old schoolmaster sent him a silver snuff box inscribed ‘To the inimitable Boz’, ‘Boz’ being the name by which he first signed himself in print. With this encouragement, he began to refer to himself as ‘the inimitable’.

14.

Annie Thackeray, given in Philip Collins (ed.),

Dickens: Interviews and Recollections

, II (London, 1981), p. 177.

1.

Having been No. 13 Mile End Terrace, then No. 387 Mile End Terrace and then No. 396 Commercial Road, the property is now No. 393 Old Commercial Road.

2.

John Dickens had met Huffam when first working in London. He had an official position as ‘Rigger to His Majesty’s Navy’, having come to official attention by rigging a privateer to fight against the French. The extra

h

in ‘Huffham’ was a mistake.

3.

See article on ancestry of Dickens in the

Dickensian

[1949], based on research by A. T. Butler and Arthur Campling, assembled by Ralph Straus.

4.

See Gladys Storey’s

Dickens and Daughter

(London, 1939), pp. 33–4. But since Annabella Crewe was not born until 1814 and would hardly have memories before 1819, she cannot have remembered old Mrs Dickens complaining about her son. Perhaps she was passing on what she had been told by others.

5.

His book collection was taken over by his son Charles in Chatham – see below.

6.

Information about Frances Crewe from Eric Salmon’s article in the

DNB

, and from Linda Kelly’s

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

(London, 1997).

7.

D reporting to F on his father’s ‘characteristic letter’, written to Catherine Dickens, and other remarks by him, [?30 Sept. 1844],

P

, IV, p. 197.

8.

An imagined episode could bring together Sheridan, aged thirty-three, with the housekeeper, aged thirty-nine, in a Crewe Hall back bedroom, and account for John Dickens’s inheriting Sheridan’s disastrous inability to live within his income, and Charles Dickens’s passion for the theatre. Too good to be true, of course.

9.

A private memorandum among Gladstone’s papers after reading the Northcote–Trevelyan Report of 1853 goes: ‘The old-established political families habitually batten on the public patronage – their sons legitimate and illegitimate, their relatives and dependents of every degree, are provided for by the score.’

10.

The announcement read: ‘On Friday, at Mile-end-Terrace, the lady of John Dickens Esq., a son.’

11.

The source is her granddaughter Katey, given by Gladys Storey in

Dickens and Daughter

, p. 25.

12.

No. 16 Hawke Street was, according to Gladys Storey in

Dickens and Daughter

, p. 40, a tiny house built without a front garden on a ‘squalid little street’. Dickens told Forster that he remembered tottering about the front garden with his sister Fanny, with something to eat in his hand, watched by a nurse through the basement window: but it cannot have been the first home, which he left long before he could walk, so perhaps it was the back garden of Hawke Street, or Wish Street. His other Portsmouth memory was of being taken to see the soldiers exercising.

13.

Mansfield Park

was written between 1811 and 1813 and published in 1814, so the Portsmouth she describes, which she knew from her brothers being at the naval school, is very much the place in which Dickens was born.

14.

Forster,

The Life of Charles Dickens

, I (London, 1872),

Chapter 1

.

15.

She died in 1893.

16.

Forster,

Life

, I,

Chapter 1

– he dates Dickens telling him this five years before the writing of

David Copperfield

, hence 1844. Dickens must have formed the phrases in his mind and kept them. In a speech given in 1864 Dickens talks about an old lady who ‘ruled the world with a birch’ and put him off print. But, by his own account, his mother taught him to read.

17.

Quoted in Philip Collins,

Dickens: Interviews and Recollections

, I (London, 1981), p. 2, taken from Robert Langton’s

The Childhood and Youth of Dickens

, first published in 1883.

18.

The spasms of pain are likely to have been caused by a kidney stone, according to ‘The Medical History of Charles Dickens’ in Dr W. H. Bowen,

Charles Dickens and His Family

(Cambridge, 1956). His reading position is described in Gladys Storey’s

Dickens and Daughter

, p. 44, presumably described by Dickens to his daughter Katey.

19.

D to F, 24 Sept. 1857, recalling his childhood in Chatham,

P

, VIII, p. 452 and fn. 5.

20.

In 1883 Alderman John Tribe, son of the old landlord of the Mitre Inn, said he had once possessed a note from his childhood friend Charles, written on John Dickens’s card, saying ‘Master and Miss Dickens will be pleased to have the company of Master and Miss Tribe to spend the Evening on …’

P

, I, p. 1.

21.

Forster,

Life

, I,

Chapter 7

, quoting from a letter Dickens wrote to the press in 1838, after being attacked for editing Grimaldi’s

Memoirs

without having seen him perform.

22.

D to Mary Howitt, 7 Sept. 1859,

P

, IX, p. 119.

23.

D to Cerjat, 7 July 1858,

P

, VIII, p. 598.

24.

The stories of the recitation and of the snuff are from Forster’s

Life

, I,

Chapter 1

, and would have been told him by Dickens himself.

25.

A version of her appears in

The Old Curiosity Shop

, where she has no name until she is called ‘the Marchioness’ by Dick Swiveller.

26.

D to F, [?27–8 Sept. 1857],

P

, VIII, p. 455.

27.

A collection of essays by Oliver Goldsmith.

1.

Walking was the way all but the rich got about. ‘We used to run to the doors and windows to look at a cab, it was such a rare sight’: this is Dickens reminiscing about life in Camden Town and thereabouts in the 1820s, before the coming of the railways, in ‘An Unsettled Neighbourhood’,

HW

, 11 Nov. 1854.

2.

Gladys Storey,

Dickens and Daughter

(London, 1939), p. 44 – she gives Harriet Ellen as her name.

3.

See D to T. C. Barrow, 31 Mar. 1836, in which he recalls the visits he made and the affectionate relationship established.

P

, I, p. 144.