Charles Palliser (107 page)

Authors: The Quincunx

“Now, Master Clothier,” Dr Alabaster began.

“Don’t call me that!” I cried.

“Why not? Is it not your name?”

“No, I hate that name!”

“Very well then, John,” Dr Alabaster resumed calmly; “these gentlemen are going to put some questions to you. Will you try to answer them?”

I nodded.

“Will you tell us,” the second stranger began, “who this gentleman is” (here he indicated Emma’s father) “and how you came to be in his house?”

“They say he is my uncle,” I said, “but I don’t know what to believe. And I don’t know how I came here. There has been a conspiracy against me. It goes back many years, you see, to the time when our house was broken into when I was a small child.

The man who did it is living in a carcase by the Neat-houses. I believe he delivered me here somehow.”

I trailed off and though I could see the two strange gentlemen turning to each other, I could not make out their expressions for their faces were mere blurred patches.

The first one now spoke: “My question is very simple. I want you to tell me how much it comes to if you add one shilling and eight-pence to six shillings and three-pence ha’penny and then take away four shillings and nine-pence three-farthings. “

My head ached and I could hardly stand. I merely shook my head and said wonderingly: “I don’t know, sir. But I’m not out of my wits. I know other things. I know that is a chair” (pointing to it) “and that is a man” (pointing to Frank).

“He can only just distinguish them,” the gentleman said, shaking his head.

“I think we have seen enough,” said the second gentlemen. “The order will be a formality.”

“I expected no other conclusion,” said Dr Alabaster.

“I hope, Mr Porteous,” the second stranger said, “that you will not deal harshly with your maid-servant. She did what she believed was right.”

“Rest assured,” Mr Porteous replied. “I think I am known to be capable of magnanimity.”

“It is fortunate,” said the first gentleman, “that you have so safe a chamber as this: the bars on the window, the lack of a chimney-piece — all of these ensure that the poor lad cannot escape and can do himself no harm.”

“That is due to a most melancholy circumstance,” replied Emma’s father. “This was the very place in which we had to confine my poor brother, this boy’s father. The son has inherited his father’s affliction.”

“No,” I cried. “That is not true! You’re lying. Or else you were lying just now.”

They shook their heads at each other and went out, and then the door was 490

THE CLOTHIERS

closed and locked. So this was the room from which Peter Clothier had made his escape to my grandfather’s house!

I remember the rest of the day and the following night as a succession of spells during which I lost and regained consciousness — I cannot call it sleeping and waking. I ate no more and felt myself growing weaker and more fevered.

Then in the midst of the darkness of oblivion I recall lights flashing suddenly into my eyes, and someone seized me and when a foul-tasting strip of cloth had been tied around my mouth, my arms, almost jerked from their sockets, were thrust into something so that I could not move them.

I was picked up and carried through the house and flung into a carriage where I found myself pinned helplessly between two strong men. As the vehicle moved off, 1 struggled and tried to scream but the bandage over my mouth prevented me.

I was struck across the head and a voice that I recognised as Dr Alabaster’s said:

“Hold your noise, Clothier, and it will go the better for you.”

I sat quietly after this. As the carriage turned into a broad, well-lighted street that must have been the New-road, I saw the face of Dr Alabaster gazing stonily through the window. I turned to look at the man on the other side of me and to my horror I recognised him: it was the tall man who had jumped into the carriage on that far-off occasion when Emma had attempted to abduct me, and who had later taken part in the attack on my mother and myself on the way back from the pawn-shop!

It came to me then that I was indeed insane. To find coincidences and connexions everywhere was proof of it. At this realization, all power of resistance was gone and I reflected that it was as well that I was being taken where I was. Indeed, there seemed to me to be an irresistible inevitability in my being delivered over to this place: it was my destiny towards which my whole life had been moving and I felt a kind of relief that it had at last been attained.

After some time the man whom I had recognised broke the silence with an unpleasant chuckle: “This is in the way of being a regular branch of the family trade, ain’t it, sir?”

“Aye,” said Dr Alabaster. “And this one has inherited a kind of reversionary interest.”

They both laughed and no more was said until after a long time the coach turned in through the gates that led to a gravelled carriage-drive. Already the night-sky was faintly suffused with light and against this I caught a glimpse of the outline of a large house. It had a strange appearance: like a wall-eyed dog I remembered seeing once, for the windows on the upper floors were whitewashed so that it was impossible to see in or out.

The vehicle stopped and I was bundled onto the gravel, picked up and dragged rather than led through the vestibule and into the entrance-hall, still with my arms secured behind my back.

Dr Alabaster went off without ceremony and his assistant was joined by a burly, ugly man who stared at me with a sneering smile as if I should know him. And now as I looked at his small squinting eyes, his eyebrows that seemed FRIEND OF THE POOR

491

to be permanently raised as if in scorn of everything he saw, and his square flat face that was exactly like a red brick, it came to me that indeed I did know him: he had been the companion of the tall man in that attack! To judge from the keys that hung from a chain round his waist, he fulfilled the function of turn-key in this place.

I was now gripped by the shoulder and pushed before these two along a dark, stone-flagged passage at the end of which we entered a large room. It was the men’s night-ward and at this early hour the patients were being awakened and dressed. I saw around me faces indicating all varieties of degeneracy, idiocy and mania: faces hardened by ill-usage and suffering, or broken by it, or borne up against it by a passionate sense of justification, or merely staring vacantly. Several were, like myself, wearing strait-waistcoats. I searched for a single face in which I could discern signs of intelligence and humanity and saw not one, until just at the end of the long room I caught the gaze of an old, white-haired man sitting on his low bed who seemed to be regarding me with an expression of interest and pity.

Then we were out of the room again and after walking down another corridor and descending some worn steps into a kind of cellar, we stopped before an iron door. The turn-key brought out a huge key from his chain. A moment later the great barred door swung creakingly open and I was pushed in.

I could make out nothing at first — except that there was deep straw on the floor for I felt it under my feet — since I was in absolute darkness, save that there was a tiny grating high up on one wall through which a little pale light crept. In a moment the door was swung to and locked behind me, but the two men remained for a moment watching me through the narrow grille on top of the door.

“Don’t get too near,” the turn-key said. “Mind how long the chain is.”

“What an affecting scene,” said Dr Alabaster’s assistant. “Like the last act of a play.”

They moved off still laughing and joking together. As silence succeeded their departure I realized that there was something in the darkness at the opposite end of the cell for I heard a faint rustling of the straw. I strained my ears and thought I detected the sound of regular breaths being drawn. I felt very afraid. I could not tell if it were an animal or if so, of what kind, and since my arms were still pinned behind my back I was helpless.

Now that my eyes were becoming adjusted to the gloom, I made out a shape against the far wall. Something was squatting on the floor. Now I saw that it resembled a human being. I heard the clinking of metal and saw that it was secured to the wall by a chain around its neck.

Slightly reassured, I took a step closer and the creature turned its face towards me and pressed itself back against the wall with its mouth hanging open and its tongue lolling out. I saw the thickly-matted hair and beard that ran together and almost covered the face, the wild staring eyes that seemed not to know which part of my visage to look at.

And to my horror I recognised the face, recognised it despite the hair and the fierce grimace, recognised it from an image that had been engraved upon my inward eye from earliest childhood. Yes, the soft brown eyes and delicate features that I had stared at so long and so often as if searching in them for the meaning of my own life, were apparent in the face that now gibbered at me in the gloom of the cell: this wretched mad creature squatting in its filth amidst the straw, bore the countenance that I knew from the miniature on my mother’s locket.

THE PALPHRAMONDS

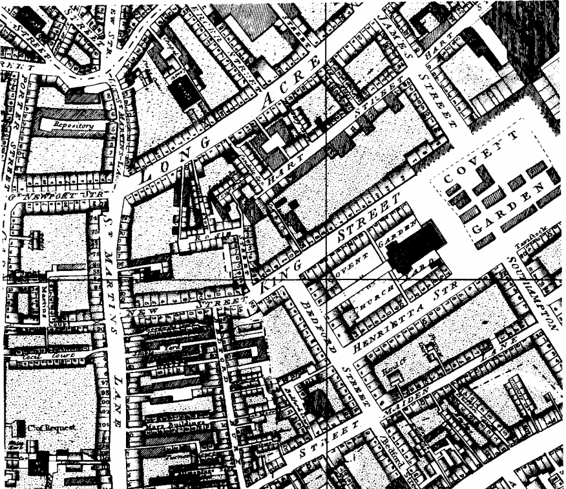

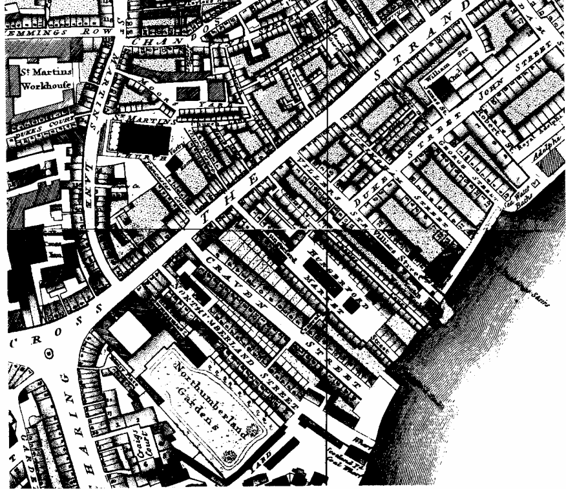

CHARING CROSS AND COVENT GARDEN (Scale: 1"=IOO yards)

The top of the page is North

The Best of Intentions

I invite you to enter in imagination the Great Parlour of the house in Brook-street and conceive how it must have been.

The elderly baronet is reclining upon an ottoman in the Drawing-room and addressing his heir, while his wife looks on from a sopha by the window:

“Outrageous! Absolutely outrageous! Almost as bad as that other rascal.”

“Your father means that your conduct is only a little less deplorable than that of your brother,” Lady Mompesson says calmly. “And less excusable, for your father and I hold him barely responsible for his actions.”

“I give him up entirely,” the baronet exclaims. “Entirely. He is being dismissed his regiment in disgrace. Never has a Mompesson …”

He breaks off and after a moment his wife continues:

“Something will have to be done with him. And whatever it is will cost money. You appear to have no conception of the gravity of the situation. We are getting more and more deeply into debt.”