Charles Palliser (29 page)

Authors: The Quincunx

Once the carriage was on the turnpike-road it gathered speed, and its regular, swaying motion was in danger of lulling me back to the sleep from which I had been snatched little more than an hour before. Although I was determined to savour every moment of the great adventure, in fact I slumbered and only awoke as we rumbled into the courtyard of the inn at Sutton Valancy.

“What hour is it?” I muttered sleepily.

“It is half after two,” my mother answered. “The night-coach departs from here at three-quarters past the hour.”

The heavy-coach called the Farmer, which rumbled along the high road from here to the far North, was waiting in the yard and almost ready to go forward. Since we were the last to board I was able to fancy that it was being kept back for us. There were people travelling overnight on top of the coach huddled under travelling-capes, and all manner of portmanteaus and bandboxes and carpet-bags and traps and boxes were strapped onto the roof and bulging from the hind-boot. There were even hampers of game and hares hanging their long ears about the coachman’s box which detracted considerably, it seemed to me, from his coachmanly dignity. We climbed into the cavernous, ill-smelling interior where the other dozen “insides” were already ensconced and had staked out their territorial claims. The guard blew a blast on his horn and the great vehicle lumbered out of the yard and turned into the silent High-street. We maintained a sedate rather than an exciting pace and I had to admit to myself that when we went up a steep hill we were travelling only at foot-pace.

After a little I asked: “Why are we going to the North? Whom do you know there?”

“Be silent, please, Johnnie,” she whispered. “I will explain later.”

However, I kept on insisting until she agreed to say more once the other passengers had fallen asleep.

Then she began to whisper: “We are not really going to the North. If anybody attempts to follow us I hope they will pursue us almost to the Borders. But in fact when we reach Gainsborough we will board the Regulator from York which leaves there at twenty minutes past five, on which I have reserved places for us.”

“The Regulator! A mail-coach!” I breathed. “Then we are going to London?”

She nodded. “We are no longer safe now that our hiding-place is known. But in London we can hide easily.”

For some minutes I considered what she had told me. Then I said: “But it’s a very silly design, Mamma, to have come this way. For the Regulator goes through Sutton Valancy on the way to London.”

“You must not speak to me like that,” she hissed.

128 THE

HUFFAMS

“Don’t you see? If someone tries to follow us but doesn’t know we have gone north, he will most likely search for us at Sutton Valancy and probably catch up with us there.”

She was hurt by my words and we sulked until I fell asleep for the rest of the stage.

However, when we arrived at Gainsborough I was so excited that I forgot I was annoyed with her. We waited in the travellers’-room but I soon found my way out to the yard.

“When is the Regulator due?” I asked a man in the royal livery of scarlet and gold.

He drew from its pocket an enormous watch: “Four and twenty minutes and forty-five seconds after five o’clock,” he announced, as if the dial had so informed him.

“I’m travelling by her,” I said, modestly.

“Are you, so? Well, she’s a tip-top goer and no mistake. Two leagues an hour she’ll keep up all the way to Lunnon. And the stoppage here for the change will only take forty-five seconds or Tom Sweetapple, her guard, will want to know why.”

At a few minutes before the time he had mentioned we heard distant blasts on the horn. Immediately the man flung open the door of the travellers’-room and bellowed:

“All out for the Regulator!”

Precisely to the second the coach, painted bright scarlet and with the royal arms blazoned on its sides, swung in through the entrance to the court-yard and like the chorus of a well-rehearsed opera the men who appeared to have been standing idly round went into action.

The coach halted in the centre of the yard and I saw the guard, holding his timepiece in his hand, stand up to shout instructions to the ostlers. Led by one of them we quickly boarded the coach, finding that the other seats were empty. I lowered the window to watch as the two “outsides” were almost thrown onto the box by the ostlers. With extraordinary speed the horses were changed, buckets of water were thrown against each of the wheels, and the letter-bags were tossed up to the guard and stowed by him in the hind-boot. Meanwhile a waiter hurried out carrying a glass which he handed up to the coachman who was buried in coats like a human cauliflower and wore a brightly-striped waistcoat and jockey boots. A hand reached out and seized it, his head was thrown back, and the glass thrust back at the waiter who stretched up on tip-toe to take it.

The coachman signalled to the guard that he was ready to go forward and the latter blew a blast on his horn. At this the ostlers threw the horse-cloths off and then scattered.

The coachman shook the reins and touched up the horses, and the vehicle seemed to surge forward like a coiled spring.

It seemed only a moment before we were out on the high road. Now we hurtled past everything that we met and nothing delayed us, for even before the turnpike lamps came in sight, the guard blew his horn to warn the ’pikemen and the gates were opened as we reached them. More and more vehicles appeared now as the dawn lightened. We overtook heavy stages that towered over us, neat little gigs that were galloping along as fast as they could go, smart broughams and elegant phaetons and chariots. Only the lightest post-chaises could keep up with us for any distance but even they were forced to halt at the ’pikes.

My mother urged me to try to sleep but there was far too much to see. It was the dawning of a beautiful day — the last of that summer — and as the coach rattled south, the rich flat farmland unrolled past us displaying its RELATIONS

129

bridges, rivers, woods, and neat little villages. There were so many things I had never seen: a lofty aqueduct arching over a steep valley, canals with barges being towed along them by patient horses, a great cathedral squatting amongst the little rooves of a town like a huge beast, and so much more.

At last I must have succumbed to sleep, for I remember coming to partial wakefulness as I was being carried from the carriage into a lighted, bustling room, and I recall moments of sleep and near-wakefulness succeeding each other until once again I was being lulled by the swaying of a carriage and the rhythmic clattering of hooves — though this time the movement was gentler and the clattering was louder.

When I awoke properly, I found myself wedged between my mother and a strange gentleman whose head lay lolled against the back of his seat and who was snoring loudly.

Opposite us sat three other travellers in a similar condition.

At intervals we rumbled into the yards of inns in little towns where we made brief stops while the guard stood beside the coach with his timepiece in his hand watching the ostlers change the horses, or longer stoppages for a hasty luncheon or a gobbled dinner. Once as we passed through a city, I poked my head out of window and looked up to see a great castle towering over the street. And once at a cross-roads I saw something hanging that seemed to be a collection of iron and bone and tarred cloth.

“What was that?” I asked.

My mother shuddered and her neighbour said : “They haven’t done that much for ten years, thank heavens.”

In the afternoon I remember looking out, as we made our way along the bottom of a gentle valley, at the water-meadows beside the little river. The countryside was of that richly golden green that it acquires late on a fine day towards the end of a wet summer.

As the sun began to sink behind the horizon a pale mist appeared over the low-lying water-meadows — so common in that country of dikes that we were passing through.

The mist was swirling around the legs of the cattle unconcernedly grazing at the edge of the water so that they looked almost as if they were wading through deep water and bending their necks in order to crop at the powdery gold that swirled about their feet.

I dozed off again, resting my head against my mother’s shoulder, and half awoke a little later to feel the weight of her own head resting against mine as she slept.

THE MOMPESSONS

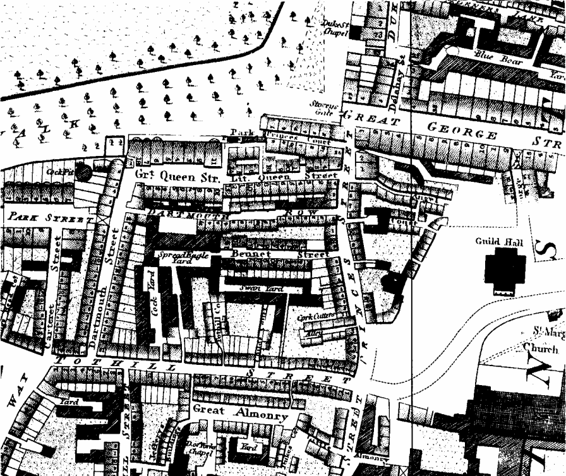

WESTMINSTER (Scale: 1"=9o yards)

The top of the page is North

Spoiled Designs

A lamp-lighter, working his way along the street of tall, dull houses upon a corner of which we are standing, blows on his cold fingers, picks up his ladder, and goes on to the next lamp. And so all down the length of the street small points of light appear, briefly flaring up before settling down to a steady glow. And now along the pavement trails a little fatherless family in rags, poor unhappy exiles of Erin, our sad sister-island.

Wretched, cold, hungry fellow-creatures! So close to the haunts of Idleness and Dissipation. We shall let noble Poverty pass by, for our business is again with Wealth, Arrogance, and Power.

For once more we are outside Mompesson-house. This time it is ablaze with lights for it is one of Lady Mompesson’s “Friday nights”. You know the kind of thing: Weipert’s band is playing quadrilles, the livery-servants are in evening dress, additional servants who have been hired from an agency are pretending to belong to the house and to know where everything is and yet keep bumping into each other and blundering into the wrong chamber. The state-rooms are dazzling and filled with the slightly honeyed fragrance of the best wax-candles.

In short, all that the insolence of Opulence can offer when Old Corruption gathers is on show, and _

But enough, for it appears that elegant writing is not what is required. Very well.

Sober truth then, without digression.

It must have been towards ten o’clock that Mr Barbellion (Power) dismounted from nothing grander than a hackney-coach and, to the contempt of the link-boys and footmen guarding the steps, was recognised by the butler and allowed to enter the house. He ascends the stairs and in the grand salon full of gentlemen in court dress and their ladies in silk and jewels, makes his way towards Lady Mompesson (Arrogance) as she looks at him with an expression as close to surprise as good breeding permits.

“This is an unlooked-for pleasure, Mr Barbellion,” she says coldly.

He appears to flush at this and perhaps it would not be too fanciful to suppose that he resents it. But no motives! That is the rule.

However that may be, he says something like: “My lady, I would not have presumed to intrude if it had not been upon a matter of the utmost urgency.

135

136 THE

MOMPESSONS

My agent has just ridden up post from Melthorpe. Mrs Mellamphy — as she calls herself — has fled.”

“Fled! And gone where?”

“To London, but beyond that I do not know.”

“You do not know, Mr Barbellion?” she repeats frigidly. At that moment a courteous smile appears on her face and she bows towards a gentleman wearing the uniform of an Imperial ambassador on the far side of the room.