Charleston (2 page)

Authors: John Jakes

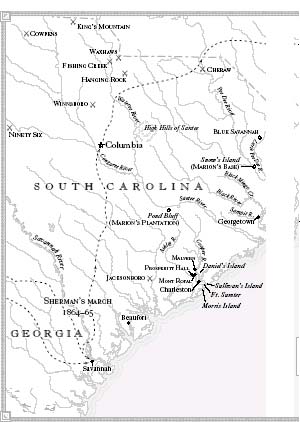

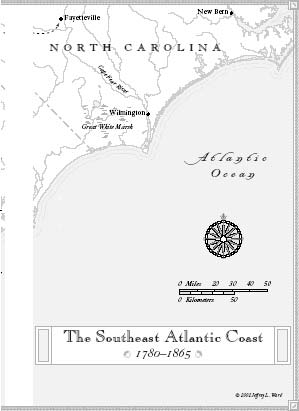

Charleston, its residents like to say, stands where the Ashley and Cooper rivers form the Atlantic Ocean. At the time of the American Revolution, Charleston was the fourth largest city in the colonies, and the most elegant. She was loved and admired by Americans and Europeans for her ambience and charm, her culture and gentility.

The foundation of Charleston's wealth was a series of dominant cash crops: indigo, then rice, then cotton, each dependent on slave labor. Charleston's white elite lived in constant fear of those it kept in servitude to insure its prosperity.

Ultimately the city, the state, and political thought became slaves of the economic system. In the struggle to preserve it Charleston moved from an open society founded on religious tolerance and the free flow of ideas to a closed society threatened by, and hostile to, the outside world. At the end of this road lay secession and bloody civil war.

This is a tale of three eras, three Charlestons, and one family that endured fires and epidemics, hurricanes and earthquakes, bombardments and military occupationsânearly a century of history that was by turns courageous, turbulent, and tragic.

Through it all, and much more that followed in the next one hundred years, Charlestonians white and black remained proud survivors, and went on to create the beautiful cosmopolitan city that greets the visitor today.

The people of Charleston live rapidly, not willingly letting go untasted any of the pleasures of lifeâ¦. Their manner of life, dress, equipages, furniture, everything, denotes a higher degree of taste and love of show, and less frugality than in the northern provinces.

Johann Schoepf, an eighteenth-century visitor

The institution of slavery shaped and defined Charleston as much as, if not more than, any other force in its history.

Robert N. Rosen,

A Short History of Charleston

The waters run out of the harbor twice a day, leaving the mudflats uncovered, and with a hot sun baking down upon decaying matter, there is an odorânot unlike that of Veniceâto let one know that all the beauty is built upon unsure foundations.

George C. Rogers, Jr.,

Charleston in the Age of the Pinckneys

South Carolina is too small for a republic and too large for an insane asylum.

Charleston Unionist James L. Petigru, on the eve of the Civil War

1720

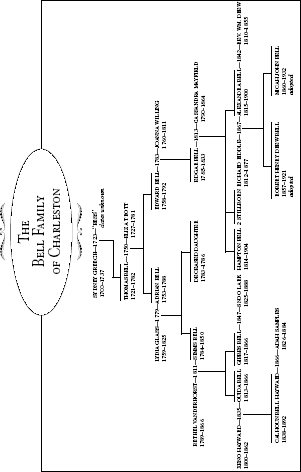

Families are sometimes the children of chance. The family of this story had its beginning at the intersection of Broad and Meeting streets, in Charles Town, on the coast of Carolina, one rainy autumn afternoon in 1720.

Charles Town was by then fifty years old. It had been established as the center of a proprietary colony organized and financed, with the king's permission, by eight wealthy Englishmen known as the Lords Proprietors. The chief organizer, Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, chose the name Carolinaâ

Carolus

, Latin for Charlesâto honor his sovereign, Charles II.

That rainy dayâno more than a steamy drizzle, reallyâa man and a woman hurried east on a footpath on the north side of a rutted mixture of sand and crushed oyster shells masquerading as a civilized street. Their destination was the Cooper River piers, where the man hoped to find menial work and cheap lodging. He was already discouraged by the sight of so many slaves, blue-black Africans, with whom he would have to compete.

He and the woman had journeyed in from a little trading station on a tributary of the Santee River. The store and stock pen of the station had long served one of the

busy trails leading northwest to the Cherokee towns, but the Cherokee slave trade was dying as more ships sailed in from West Africa. The man and woman had abandoned the place because of poverty, loneliness, and the woman's delicate condition.

On the southeast corner of Broad and Meeting stood a small Anglican church built of cypress. From somewhere within the palisade surrounding the church a bell rang the hour. The man stopped to listen. He'd always loved the sound of bellsâship's bells, handbells of street criers, and especially the mighty cathedral bells of his native England, which he'd left as a boy. This bell was thin by comparison but sweet all the same.

Sydney Greech, late of Bristol, Barbados, and the sloop

Royal James

, was now twenty. He had a certain lean good looks, though his eyes possessed a hardness born of his recent career at sea. The best that could be said about the young woman was that she still had a prettiness not yet ruined by harsh living conditions or the kind of debauchery in which she and Sydney liked to indulge. She called herself Bess; no last name ever came down to later generations.

A widow at seventeen, Bess had met Sydney in 1718, when he stumbled into her late husband's trading station, lost and starving. Finding each other by accident, they lived together and took care of the business until deciding to leave it for the bustling town.

The sonorous peal of the church bells moved Sydney to say, “'Spose we should be officially married someday.”

“'Spose we should, since I'm carrying your babe.”

“Not very familiar wi' churches. Truth is, never stepped inside one.”

“I did, once. But I got something else on my mind about marrying.”

“What?”

“Our name. Don't be mad now, Sydney. It's been in my thoughts every day because of the baby.”

“What exactly?”

“Greech. It don't sound pretty on the tongue. It don't sound important. It sounds low.”

Incensed, he flung down her hand. “Goddamn you, woman, it's the name my dear mother gave me, I won'tâ”

There he stopped. Sydney wasn't a brilliant or educated young man, but neither was he completely insensitive. He saw the hurt in Bess's eyes, the tears mingling with rain, and reconsidered. “Oh, I guess maybe there's something in what you say. What ought we do about it?”

“Change our name to a better one that fits the kind of life we'll have from now on. We're going to do well in Charles Town, I know it.” As if to reinforce that statement the baby kicked vigorously. She had no doubt it was a boy.

As the last bell notes floated into the rainy sky, Sydney rubbed his jaw. “All right, then. You know I love bells.

Bell

is a pretty word all by itself. Bells are strong, made of fine metal. Bells do important business in this world.”

Excitement showed on her grimy face. “Yes, they do, Sydney.”

“Well, do you like Bell for a name?”

“Oh, yes, very much.”

“Then Bell it is,” he said. Thus he settled the issue and set a stormy future in motion.

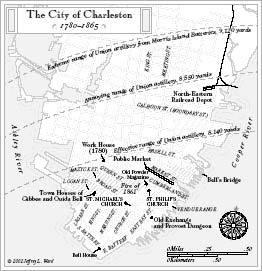

CITY AT WAR

1779â1793

All their cavalry was annihilated. Our works came up to their ditch. Fort Moultrie and the entire harbor were in our hands. They could not entertain the least hope of succor.

Diary of Captain Hinrichs,

Hessian Jäger Corps, at the siege of Charles Town

May 1780

The city looks like a beautiful villageâ¦. It is built at the end of the Neck between the Cooper and Ashley rivers and is approximately a good English mile long and half a mile wide. The streets are broad and intersect one another at right angles. Most of the buildings are of wood and are small; but near the rivers one sees beautiful buildings of brick, behind which there are usually very fine gardensâ¦. If one can judge from appearances, these people show better taste and live in greater luxury than those of the northern provinces.

Diary of Captain Ewald,

Hessian Jäger Corps, British army of occupation

May 1780

The safe rule, according to which one can always ascertain whether a man is a loyalist or a rebel, is to find out whether he profits more in his private interests, his mode of life, his way of doing things, when he is on our side or on that of the enemy.

Diary of Captain Hinrichs