Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (6 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

10.27Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

For the first time in his life, Vieira de Mello felt he was doing something practical to operationalize his philosophical commitment to elevating individual and collective self-esteem. Human suffering—starvation, disease, displacement—would never be abstractions for him again. “Bangladesh was a revelation for Sergio,” recalls his Brazilian friend da Silveira.“By being in the field, he recognized a part of himself he had never seen before. He understood he was a man of action. He was made for it.”

Around the same time that Vieira de Mello had fallen under Jamieson’s spell, he met Annie Personnaz, a French secretary at UNHCR. The two began dating, and just as Arnaldo had done with Gilda’s family, Vieira de Mello grew close to Annie’s parents, who owned a family hotel and spa in Thonon, France.

In May 1972 Jamieson, who was sixty, retired in accordance with UN rules. He was miserable and kept his eyes glued to the newspapers for a chance to return to duty. When the government of Sudan signed a peace agreement with southern rebels, seemingly ending a seventeen-year civil war and paving the way for the return of some 650,000 Sudanese refugees and displaced persons, Jamieson saw his opportunity and persuaded the high commissioner to ask him to come out of retirement to lead the effort. Just as Vieira de Mello’s courtship with Annie was intensifying, Jamieson asked him to join a small team helping organize the return of the Sudanese refugees. Vieira de Mello wrote Annie letters while he was in southern Sudan, and she even visited him in the capital, Juba. He soon pro-posed,

and they scheduled their wedding for June 2, 1973. Flavio da Silveira would be his best man.

Vieira de Mello (

in a light-colored suit, third from left

) walking in Dhaka, Bangladesh, with a delegation that included UNHCR’s high commissioner Sadruddin Aga Khan (

far right

), November 1972.

in a light-colored suit, third from left

) walking in Dhaka, Bangladesh, with a delegation that included UNHCR’s high commissioner Sadruddin Aga Khan (

far right

), November 1972.

The Sudan mission afforded Vieira de Mello the chance to work more closely with Jamieson than he ever had before. Rotating between Geneva, Khartoum, and Juba, he helped his mentor establish an airlift that transported food, medicine, farming tools, and the returning refugees themselves. Jamieson could be an ingenious problem-solver. When he saw that an antiquated barge was the only means of carrying commercial traffic across the Nile River, he declared, “If we’re going to bring these people home, we need a bridge.” But UNHCR passed out food; it didn’t build bridges. So Jamieson began appealing to Western governments.When he made the case on charity grounds alone, he got nowhere. But in discussions with the Dutch government, he found an argument that worked. “This will be a training exercise,” Jamieson said. “The Dutch military engineers can use this as a drill to see how quickly they can build a bridge in difficult circumstances.” Initially Jamieson’s scheme looked doomed because the Sudanese rejected the presence of Western soldiers on their soil, and the Dutch military refused to perform the task out of uniform. But Jamieson quickly devised a compromise formula by which the Dutch would wear their uniforms without Dutch insignia. The all-steel Bailey bridge, which was completed in the spring of 1974, opened up southern Sudan to Kenya and Uganda, vastly increasing the flow of people and goods into the area.

Vieira de Mello watched Jamieson take what he had seen in the field and turn it into a fund-raising pitch at headquarters. At a press conference in Geneva in July 1972, decked out in a suit and tie, with a matching handkerchief and prominent cuff links, Jamieson argued that what the Sudanese wanted was not emergency relief but development assistance.“I found they are more interested in seeing something long-range done for their children, than in food,” he said. “Strange. I’d like to see

us

in similar circumstances. I’d ask for fish-and-chips first and then talk about education second.”

19

Vieira de Mello saw that while UNHCR had become skilled at feeding people in flight, governments were far less adept at preventing crises in the first place, or at rebuilding societies after emergencies so they could become self-sufficient.

us

in similar circumstances. I’d ask for fish-and-chips first and then talk about education second.”

19

Vieira de Mello saw that while UNHCR had become skilled at feeding people in flight, governments were far less adept at preventing crises in the first place, or at rebuilding societies after emergencies so they could become self-sufficient.

Jamieson carried his taste for scotch with him on the road, and Vieira de

Mello eagerly joined in. “Don’t bother with antimalaria pills,” Jamieson told a young Iranian colleague Jamshid Anvar. “Whiskey is the best vaccine for everything.” But the drinking took its toll. Jamieson’s complexion grew ruddier, and in May 1973 he suffered a mild heart attack. The doctor told him to ease his workload.

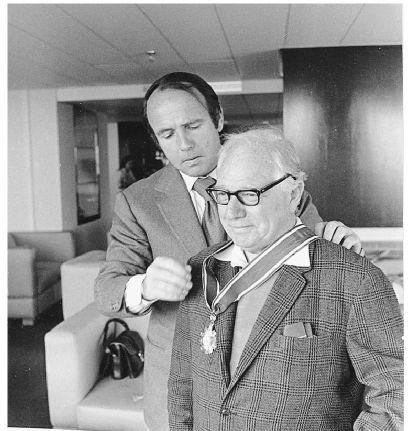

High Commissioner Sadruddin presenting Thomas Jamieson with the Sudanese Order of the Two Niles on behalf of Sudanese president Jaafar Nimeiri, 1973.

Vieira de Mello juggled his own duties in Sudan with the planning of his wedding in the French countryside. He had invited both of his parents to attend the ceremony, but Arnaldo declined. Back in Brazil, without work, he had retreated further into himself. His drinking picked up, and his health grew worse. His depression had deepened in 1970 when his youngest brother, Tarcilo, was killed by a passing car as he exited a taxi in Rio. Gilda urged her husband to reconsider their son’s wedding invitation, but Arnaldo said that he was only halfway through his second book and needed to finish. Gilda was upset. “How am I going to attend my son’s wedding ceremony by myself?” she asked. “I want to go with my husband. I am not a widow.” But Arnaldo insisted that on his small pension he could not afford to buy new suits for both the religious and the civil ceremonies, and he would not appear in the same suit at the two events. In all likelihood he was not feeling well enough to travel.

Gilda, Sonia, and André, Sonia’s six-year-old son and Vieira de Mello’s godson, flew to France for the wedding. On June 12,1973, ten days after the couple had wed, Sonia, who had traveled on to Rome, received a telephone call from a friend in Rio: Arnaldo, fifty-nine, had suffered a stroke and pulmonary edema and died. Gilda, who was reached in London, was devastated. Vieira de Mello had driven with Annie across Europe to Greece. The couple had just arrived at the hotel to start their honeymoon when he got the news. Vieira de Mello had worried about his father’s health for years and was not surprised, but he was deeply saddened. He put the couple’s luggage back into the car, drove back to France, and flew alone to Brazil, where he arrived in time for the memorial service. In 1992, after years of trying to find a publisher for his father’s incomplete manuscript, Sergio would himself pay to have it published in Brazil.

20

20

With the sudden death of his father, Vieira de Mello grew even closer to his mother. For the rest of his life, no matter where he went in the world, he made a point of speaking to her at least once—but usually several times—each week. She also became a one-woman clipping service, tearing out articles from the Brazilian press that pertained to the places her son had worked.Vieira de Mello’s ties to Jamieson also grew more intense. Jamieson had taken one lesson from his heart attack: Work was a “blessing,” and he needed to get back to it. He had always been dismissive of physical hazards of any kind. When two of his colleagues were badly injured in an attack in Ethiopia, High Commissioner Sadruddin had considered withdrawing UN staff, but Jamieson had ridiculed the idea. “Prince, look,” he had said, “if you don’t want to take any risks, you might as well go out and sell ice cream.”

Jamieson maintained an indefatigable pace, ignoring his doctor’s orders to avoid the scorching equatorial sun. Often with Vieira de Mello by his side, he crisscrossed the vast Sudan, personally visiting camps and villages to ascertain whether returning refugees would have the water and fertile soil they needed in order to survive. In late 1973, while Jamieson was visiting refugee camps in the eastern part of the country, he collapsed and was rushed by plane back to Khartoum. The doctors told him his heart condition was severe but released him so that he could spend the night back in his room at the Hilton Hotel. A panicked Vieira de Mello helped to arrange the medical evacuation to Geneva and volunteered to remain by Jamieson’s bedside throughout the night.

Anvar, the Iranian UNHCR official, had been with Jamieson when he collapsed. When he spotted Vieira de Mello at the hotel, he said,“Sergio, you must be crazy to want to stay up all night with him.”

“He might need help,” Vieira de Mello said.

“He is in absolutely no danger,”Anvar said. “The hospital would not have released him if there was a risk.”

“I will not be able to sleep,” Vieira de Mello said. “And I don’t trust doctors anyway.”

“I don’t understand you,” Anvar countered. “Jamie is condescending and patronizing toward anybody who isn’t British. He is everything that you are not and you are everything that he isn’t. What do you see in him that I can’t see?”

“He’s like a father to me,” Vieira de Mello said simply. "I love the man.”

The following day Vieira de Mello flew with Jamieson back to Geneva. Jamieson survived the incident but never returned to the field or recovered his health. He died in December 1974 at the age of sixty-three.

Vieira de Mello turned back to developing his philosophical theories, which had taken a practical turn. On returning to Geneva from Bangladesh, he had reached out to Robert Misrahi, a philosophy professor who specialized in Spinoza at the Sorbonne and whom he had studied with in the past. “He was a young student settling down intellectually,” Misrahi remembers. “He was extremely intelligent and dynamic, but he was without a doctrine. Fueled by painful personal experiences—his father’s firing, his own exile, and what he had witnessed in Bangladesh—he wanted to be a man of generous action or a man of active generosity.”

21

Under Misrahi’s supervision, Vieira de Mello completed a 250-page doctoral thesis in 1974, entitled “The Role of Philosophy in Contemporary Society.” He took several months of special leave without pay to finish up, relying upon Annie’s UNHCR salary. Forgiving of her new husband’s relentless work habits, she threw herself into the process, typing up his manuscript for submission.

21

Under Misrahi’s supervision, Vieira de Mello completed a 250-page doctoral thesis in 1974, entitled “The Role of Philosophy in Contemporary Society.” He took several months of special leave without pay to finish up, relying upon Annie’s UNHCR salary. Forgiving of her new husband’s relentless work habits, she threw herself into the process, typing up his manuscript for submission.

The thesis took aim at philosophy itself, which he deemed too apolitical and abstract to shape human affairs. “Not only has history ceased to feed philosophy,” he wrote, “but philosophy no longer feeds history.” He credited Marxism with being the rare theory that attempted to play a role in real-life human betterment. By defining the contours of a social utopia, Vieira de Mello argued, Marxism at least laid out benchmarks that could inspire political action. Although he was pleading for a more relevant and political philosophy,Vieira de Mello wrote in the dense, jargon-filled style of Paris in the 1970s. He argued that the core philosophical principle that should drive human and interstate relations was “intersubjectivity,” or an ability to step into the shoes of others—even into the shoes of wrongdoers. If philosophers could help broaden each individual’s ability to adopt another’s perspective, he argued, they could help usher in what Misrahi called a “conversion.”

22

22

UNHCR continued to offer assignments that kept pace with his growing appetite for adventure and learning. In 1974, still just twenty-six, he helped manage the mechanics of aid deliveries to Cypriots displaced in the Greek-Turkish war. “Leave all the logistics to me,” the young man told Ghassan Arnaout, his Syrian supervisor in Geneva. “You keep your mind on the political and the strategic picture, and I’ll handle the groceries.” Vieira de Mello already seemed to view the assistance that UNHCR gave refugees— or “grocery delivery”—as a routine household chore. He had a lot to learn about protecting and feeding refugees, but if he remained within the UN system, he told Arnaout, he hoped to eventually involve himself in high-stakes political negotiations.

Other books

The Nonesuch and Others by Brian Lumley

The Accidental Assassin by Nichole Chase

Riccardo by Elle Raven, Aimie Jennison

Negative by Viola Grace

The Press: A Halloween Short Story by Masterton, Graham

Twice Told Tales by Daniel Stern

Fear to Tread by Michael Gilbert

Incubi - Edward Lee.wps by phuc

Conquest ~ Indian Hill 3 ~ A Michael Talbot Adventure by Tufo, Mark

Me llamo Rojo by Orhan Pamuk