Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (72 page)

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

5.9Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Deciding just who belonged on the twenty-five-member council was no easy task. Vieira de Mello, who had spent the previous six weeks building his Rolodex, served as an intermediary between Bremer and Iraqi political, religious, and civic leaders. He pushed Bremer to allow the secretary-general of the Communist Party, Hamid Majeed Mousa, to be included. He urged that Bremer take special care to maximize Sunni membership. Aquila al-Hashimi, who had helped to arrange Vieira de Mello’s meetings in Najaf, made the cut, becoming one of just three women on the council. And he was pleased by Bremer’s appointment of Abdul Aziz al-Hakim of SCIRI, despite al-Hakim’s links to Iran. Only high-level Ba’athists were excluded.

Vieira de Mello felt proud of his contributions to the Governing Council. In a cable back to UN Headquarters in early July, he wrote that “Bremer was at pains to state that our thinking had been influential on his recalibrations.” He noted that the CPA demonstrated a “growing understanding” that the “aspirations and frustrations of Iraqis need to be dealt with by greater empathy and accommodation and that the UN has a useful role to play in this regard.”

23

Vieira de Mello saw it as a victory that only nine of the twenty-five Iraqi members of the body were exiles. But from the Iraqi perspective, six of the thirteen Shiite representatives and three of the five Sunnis were exiles, and neither the inclusion of five Kurdish representatives who had lived in northern Iraq under Saddam nor the addition of Turkmen or Christian representatives appeased the Sunni population.

24

Vieira de Mello hailed the fact that the Governing Council had the power to appoint interim ministers and propose policies, but Iraqis saw that Bremer was left with the authority to veto any of the new body’s decisions.

23

Vieira de Mello saw it as a victory that only nine of the twenty-five Iraqi members of the body were exiles. But from the Iraqi perspective, six of the thirteen Shiite representatives and three of the five Sunnis were exiles, and neither the inclusion of five Kurdish representatives who had lived in northern Iraq under Saddam nor the addition of Turkmen or Christian representatives appeased the Sunni population.

24

Vieira de Mello hailed the fact that the Governing Council had the power to appoint interim ministers and propose policies, but Iraqis saw that Bremer was left with the authority to veto any of the new body’s decisions.

The UN staff were split again, this time on whether to embrace this new body. Vieira de Mello argued that, despite its manifest imperfections, the Governing Council was the “only game in town.”

25

“We have to take the leap of faith,” he said. At last Iraq would have a recognized body, and the UN would be able to offer its services to it rather than to the Americans. “This is only a start,” he insisted. “But it is a necessary start in the same way the first mixed cabinet in East Timor was a start.”

25

“We have to take the leap of faith,” he said. At last Iraq would have a recognized body, and the UN would be able to offer its services to it rather than to the Americans. “This is only a start,” he insisted. “But it is a necessary start in the same way the first mixed cabinet in East Timor was a start.”

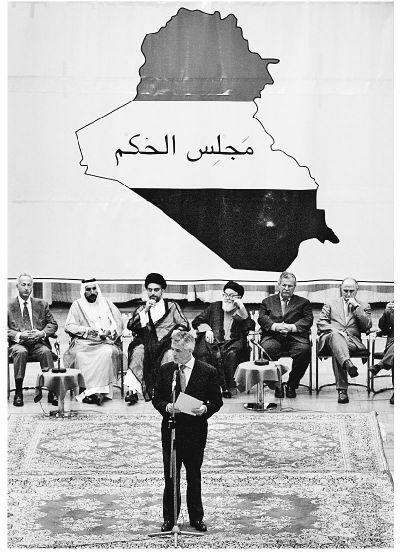

He attended the inauguration of the council on July 13, 2003.The members of the Governing Council acted as though they had not been appointed by the Coalition but had simply congealed into a body on their own. In a carefully staged visual the council summoned Bremer, Sawers, Crocker, and Vieira de Mello and “self-proclaimed themselves.” Vieira de Mello was the only non-Iraqi asked to speak at the ceremony. Wearing a pale blue tie to remind the audience of the organization he represented, he began and closed his remarks in Arabic:

“Usharifuni, an akouna ma’akum al-yaom. Wa urahhib bitashkeel majlis al-hokum.”

Although he knew few words, he pronounced them effortlessly: “It is an honor to be with you today. And I welcome the formation of the Governing Council.” He hailed the gathering as the first major step toward the return of Iraqi sovereignty, and he pledged ongoing UN support. “We are here, in whatever form you wish, for as long as you want us,” he told the beaming council members.

26

Crocker watched him admiringly. "He was wrapping the blue flag around what we were trying to do politically. I thought it was an act of real political courage. It was also an act of unbelievable physical courage, although we didn’t see it at the time.”

“Usharifuni, an akouna ma’akum al-yaom. Wa urahhib bitashkeel majlis al-hokum.”

Although he knew few words, he pronounced them effortlessly: “It is an honor to be with you today. And I welcome the formation of the Governing Council.” He hailed the gathering as the first major step toward the return of Iraqi sovereignty, and he pledged ongoing UN support. “We are here, in whatever form you wish, for as long as you want us,” he told the beaming council members.

26

Crocker watched him admiringly. "He was wrapping the blue flag around what we were trying to do politically. I thought it was an act of real political courage. It was also an act of unbelievable physical courage, although we didn’t see it at the time.”

Vieira de Mello knew that some on his staff would have preferred for him to avoid any association with the Coalition. He continued to have heated exchanges with Marwan Ali, his political aide. “Sergio, don’t you see, you’re not changing the Americans.You are helping the Americans.” But Vieira de Mello believed he was making progress and that Bremer could still go either way. The two men were getting along well. They were both handsome, charismatic, hyperachieving workaholics who knew how to take charge. Although Bremer had close ties to the neoconservatives, who were known for their anti-UN fervor,Vieira de Mello believed that Bremer was cut from a different cloth because he spoke French, Dutch, and Norwegian. This gift for languages testified to a curiosity and a breadth of perspective that he did not often find among Americans. “I’ve been giving Bremer advice on how to manage the hurt pride of the Iraqis,” he told Jonathan Steele of the

Guardian.

“There’s been a gradual change in him. Everything I’m telling you, he buys.” Although Vieira de Mello had resisted his appointment to Iraq, he found the first two months of the mission exhilarating. He felt as though he was actually making inroads with the Coalition and with the Iraqis, and he naturally loved being at the center of what felt like the geopolitical universe. In an e-mail he asked Peter Galbraith why he intended to spend just a single day in Baghdad, noting that the Iraqi capital was where things were “happening . . . good and bad.”

27

Guardian.

“There’s been a gradual change in him. Everything I’m telling you, he buys.” Although Vieira de Mello had resisted his appointment to Iraq, he found the first two months of the mission exhilarating. He felt as though he was actually making inroads with the Coalition and with the Iraqis, and he naturally loved being at the center of what felt like the geopolitical universe. In an e-mail he asked Peter Galbraith why he intended to spend just a single day in Baghdad, noting that the Iraqi capital was where things were “happening . . . good and bad.”

27

Occasionally, though, he grew frustrated over Bremer’s mixed messages. He complained about the “5 p.m. syndrome,” where, he said, “I have my Bremer till 5 p.m. [or 9 a.m. D.C. time], and after 5 p.m. Washington has its Bremer.”

28

But because of his own experience being micromanaged by UN Headquarters, he sympathized with the “long screwdriver” that Bremer fought off from his higher-ups in the United States. “Bremer will succeed if he makes himself Iraq’s man in Washington rather than Washington’s man in Iraq,” he told the

Washington Post

’s Rajiv Chandrasekaran over a drink. He had saved the UN mission in East Timor only by coming to that realization himself.

28

But because of his own experience being micromanaged by UN Headquarters, he sympathized with the “long screwdriver” that Bremer fought off from his higher-ups in the United States. “Bremer will succeed if he makes himself Iraq’s man in Washington rather than Washington’s man in Iraq,” he told the

Washington Post

’s Rajiv Chandrasekaran over a drink. He had saved the UN mission in East Timor only by coming to that realization himself.

In conversations with visitors at this time, he swung between two extremes. On the one hand he acknowledged that the UN was a “minor player” on the scene and confessed embarrassment at its “total lack of authority.” He frequently reminded visitors: “The UN is not in charge here. The Coalition is.” But he also stressed, perhaps to convince himself, that the United Nations would not be “a rubber-stamping organization for whatever the military occupiers decide,” and he insisted that many Iraqis saw the UN as the guardian and promoter of Iraqi sovereignty.

29

He believed that the UN role would expand over time, and he expected it would be the United Nations that would help organize the country’s first free elections. He was convinced that no other body could meet twenty-first-century challenges.“Iraq is a test for both the United States and for the UN,” he said in an interview with a French journalist in Baghdad. “The world has become too complex for only one country, whatever its might, to determine the future or the destiny of humanity. The United States will realize that it is in its interest to exert its power through this multilateral filter that gives it credibility, acceptability and legitimacy. The era of empire is finished.”

30

While he was correct that the United States would eventually need the UN in Iraq, he was wrong in thinking that Washington was close to recognizing this.

29

He believed that the UN role would expand over time, and he expected it would be the United Nations that would help organize the country’s first free elections. He was convinced that no other body could meet twenty-first-century challenges.“Iraq is a test for both the United States and for the UN,” he said in an interview with a French journalist in Baghdad. “The world has become too complex for only one country, whatever its might, to determine the future or the destiny of humanity. The United States will realize that it is in its interest to exert its power through this multilateral filter that gives it credibility, acceptability and legitimacy. The era of empire is finished.”

30

While he was correct that the United States would eventually need the UN in Iraq, he was wrong in thinking that Washington was close to recognizing this.

On July 21, he flew to New York, where he briefed the Security Council the following day. Defending the Governing Council’s representativeness, he stressed,“What the Council needs at present is not expressions of doubt; it is not skepticism, it is not criticism, that is too easy. What it needs is Iraqi support [and] ... the support of neighboring countries.”

31

Resolution 1483 had given the UN almost no formal authority, but he genuinely believed that his small political mission had made a tangible difference. “Can you believe we stretched our marginal mandate as far as we did?” he asked Salamé.

31

Resolution 1483 had given the UN almost no formal authority, but he genuinely believed that his small political mission had made a tangible difference. “Can you believe we stretched our marginal mandate as far as we did?” he asked Salamé.

Despite his optimism, one thing worried him: the deteriorating security climate. “The United Nations presence in Iraq remains vulnerable to any who would seek to target our organization,” he said in his remarks before the Security Council. “Our security continues to rely significantly on the reputation of the United Nations, our ability to demonstrate, meaningfully, that we are in Iraq to assist its people.” Two days before his testimony an Iraqi driver with the UN-affiliated International Organization for Migration

(IOM)

had died in Mosul when he swerved into a bus in an effort to evade the gunfire coming from a passing car. And on the very day Vieira de Mello testified, a Sri Lankan with the International Committee of the Red Cross had been killed south of Baghdad.Vieira de Mello mentioned both attacks in his testimony and stressed that the Coalition bore responsibility for security. As he wound down his remarks, a woman in the gallery shouted out her criticism of the Governing Council. “This is not a legitimate body,” she yelled, “and you know that!” In the press briefing afterward, a reporter asked Vieira de Mello to elaborate on his security concerns. He said that the Shiite south and mainly Kurdish north were peaceful. “What you have is a triangle, Baghdad, the north and the west, that are particularly dangerous and risky for Coalition forces. And more recently I’m afraid for internationals as well.”

32

These were Vieira de Mello’s last words on the record before returning to Iraq.

(IOM)

had died in Mosul when he swerved into a bus in an effort to evade the gunfire coming from a passing car. And on the very day Vieira de Mello testified, a Sri Lankan with the International Committee of the Red Cross had been killed south of Baghdad.Vieira de Mello mentioned both attacks in his testimony and stressed that the Coalition bore responsibility for security. As he wound down his remarks, a woman in the gallery shouted out her criticism of the Governing Council. “This is not a legitimate body,” she yelled, “and you know that!” In the press briefing afterward, a reporter asked Vieira de Mello to elaborate on his security concerns. He said that the Shiite south and mainly Kurdish north were peaceful. “What you have is a triangle, Baghdad, the north and the west, that are particularly dangerous and risky for Coalition forces. And more recently I’m afraid for internationals as well.”

32

These were Vieira de Mello’s last words on the record before returning to Iraq.

Twenty

REBUFFED

The first gathering of the Iraqi Governing Council in Baghdad, July 13, 2003.

After Vieira de Mello helped Bremer with the formation of the Governing Council, his influence diminished and his renowned political instincts let him down.The Coalition had relied on him in late June because he brought expertise on political transitions and because he had familiarity and credibility with a variety of Iraqi political and religious forces. But paradoxically, by serving as a talent spotter, he had made himself dispensable. Once Bremer was able to work directly with the Governing Council, he had less need for a UN intermediary. Similarly, prominent Iraqis who had previously used Vieira de Mello to convey their views to Bremer found it easier to negotiate directly with the Americans.

Vieira de Mello was sad to see Ryan Crocker and British ambassador John Sawers leave Baghdad at the end of July. Bremer was surrounding himself with advisers who seemed more hostile to the UN. Vieira de Mello told one visitor that “the more neocon side of Jerry’s personality” was emerging.

1

1

While in New York, after briefing the Security Council, he had turned up in the office of his colleague Kieran Prendergast and plopped down on Prendergast’s couch. “My god,” he had said, “I need a drink.” He and Prendergast were not friends, but the two men had worked together more closely while he was in Iraq than they had before. Prendergast produced a bottle of Mongolian vodka with golden flecks inside that an aide had brought back from a recent trip. “That looks awful,” Vieira de Mello said, “but it will do.” After taking several swigs of the spirit, he said that the Americans and Iraqis were already showing signs of losing interest in UN help. Then sure enough, as soon as he got back to Baghdad, the Iraqis on the Governing Council began prevaricating and delaying when he tried to meet with them. They told him that he was welcome to join them after an upcoming lunch with Bremer, while coffee was being served.“He was like a Victorian parlor maid,” recalls Prendergast. “Seduced and discarded.”

Vieira de Mello had hoped the Iraqis on the Governing Council would rise to the occasion and actually govern by exercising the limited authority they had been given. But they were doing the opposite, spending most of their time squabbling. He suggested the council would be better off if it were funded by the UN (rather than the United States and the U.K.) and if it received assistance from UN technical advisers. But Iraqi council members were not interested. He wrote to Headquarters that their behavior did “not indicate a particular willingness for compromise.”

2

They seemed woefully out of touch with ordinary Iraqis and were operating, he complained, “in a kind of cocoon.”

3

2

They seemed woefully out of touch with ordinary Iraqis and were operating, he complained, “in a kind of cocoon.”

3

But if the choice was between absolute U.S. rule and flawed Iraqi rule, Vieira de Mello would take the Governing Council. To persuade Iraq’s neighbors to give the council “the benefit of the doubt,” he went on a whirlwind tour of the region. On a trip to Turkey, he met with the Turkish and Indian foreign ministers. He visited Crown Prince Abdullah in Saudi Arabia. More than three years before the Iraq Study Group (chaired by James Baker and Lee Hamilton) would urge the Bush administration to enlist Iraq’s neighbors, he tried to do so, flying to Damascus and Tehran to meet with President Bashar al-Assad and President Mohammad Khatami. In Amman he met with the foreign ministers of Egypt and Jordan. And in Egypt he met with Amr Moussa, the secretary-general of the Arab League.

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

5.9Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Leaving Yesterday by Kathryn Cushman

Dogs at the Perimeter by Madeleine Thien

Business Without the Bullsh*t: 49 Secrets and Shortcuts You Need to Know by Geoffrey James

Point of Balance by J.G. Jurado

The Oxford dictionary of modern quotations by Tony Augarde

Dragons Reborn by Daniel Arenson

Eye to Eye by Grace Carol

The Mummy's Curse by Penny Warner

Beautiful Girl by Alice Adams

Rivalry by Jack Badelaire