Chesapeake (114 page)

Authors: James A. Michener

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Family Saga, #Sagas, #Historical, #Action & Adventure, #General, #Romance, #Eastern Shore (Md. And Va.), #Historical Fiction, #Fiction, #Chesapeake Bay Region (Md. And Va.)

All their lives the slaves had heard about Proverbs and Peter, and now even though Reverend Buford glossed them with his special rhetoric, they grew restless. Some stared at the violent movement of his Adam’s apple and whispered, ‘He gonna choke hisse’f!’ and others began to fidget. Buford knew how to handle this; he had two additional arrows in his quiver, and when he shot these at the slaves, they listened, for the first contained a definite threat:

‘You look at Mr. Sanford sitting there and you think, “He has it easy!” But you don’t know that Mr. Sanford has obligations at the bank, and he must gather up the money, a dollar at a time, working hard to do so, and pay that money to the banker, or he will lose this plantation. The banker will come down here and take it away and sell every one of you to Louisiana or Mississippi.’

He recited other heavy obligations of the white folk sitting in the shade; this one had examinations to pass at Princeton, that one had to care for

the sick, and he, Reverend Buford, was obligated to the fine people who ran his church. The world was crammed with duties, and some of the lightest were those borne by slaves.

It was his second arrow that gave Buford his peculiar force in pacifying slaves, and it was from this that his famous sermon took its name:

‘At dinner today Mr. Sanford told me that he had never had a finer bunch of slaves than you. “They work hard,” he told me. “They mind the crops. They wouldn’t steal a single one of my chickens.” Yes, that’s what Mr. Sanford told me. He said that you were the most honest slaves in Maryland, but then he added something which shocked me. He said that some of you had been thinking of running away. And what is running away, really? Tell me, what is it? It is theft of self. Yes, you steal yourself and take it away from the rightful owner, and God considers that a sin. In fact, it’s a worse sin than stealing a chicken or a cow or a boat, because the value of what you have stolen is so much greater. Mr. Sanford owns you. You belong to him. You are his property, and if you run away, you are stealing yourself from him. And this is a terrible sin. If you commit this sin, you will roast in hell.’

At this point Reverend Buford liked to spend about fifteen minutes describing hell. It was filled primarily with black folk who had sinned against their masters; there was an occasional white man who had murdered his wife, but never anyone like Herman Cline, who had murdered two of his slaves. It was a horrendous place, much worse than any slave camp, and it could be avoided by one simple tactic: obedience. Then the preacher came to his peroration, and it became evident why he insisted upon the attendance of the white masters:

‘Look at your master sitting there, this kind man surrounded by his good family. He spent long years working and saving and in the end he had enough money to buy you. So that you could live here along this beautiful river rather than in a swamp. Look at his beautiful wife, who comes out at night to your cabins to bring you medicine. And those fine children that you helped to bring up, so that you would have good masters in the years to come. These are the good people who own you. Now, do you want to injure them by stealing yourself, and hiding yourself up North where they cannot find you? Do you want to deprive Mr. Sanford of property he bought and paid for? Do you want to go against the word of God, the commands of Jesus Christ, and make those fine people lose their plantation?’

He preferred at this point for the owners to start weeping, for then some of the older slaves would weep, too, and this gave him an opportunity

for a ringing conclusion, with the white folk in tears, the slaves shouting, ‘Amen! Amen!’ and all ending in a rededication to duty.

It was a fine thing to hear Reverend Buford speak; he delivered his

Theft of Self

sermon at eight major plantations, ending at Devon Island, where Paul Steed entertained him in the big house prior to his performance.

‘You’ve matured since we last met,’ Steed said. ‘You’ve become quite a manager,’ Buford responded. ‘Last time it was all books. This time all work.’

‘What do you hear in Virginia?’ Steed asked.

Buford was no fool. He circulated in the best circles and kept his ears open. ‘We find ourselves resisting agitators from both ends.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘The abolitionists pressure us from the North to free our slaves, and the secessionists from South Carolina pressure us to leave the Union.’

‘What will you do?’

‘Virginia? We’ll make up our own minds.’

‘To do what?’

For the first time during his foray to the Eastern Shore, Reverend Buford was at a loss for words. He leaned back in his chair, looked out at the lovely gardens, and after a long hesitation, replied, ‘If men like you and me can keep things calmed down just a little longer, we’ll stabilize this agitation. We’ll strike a balance between North and South. Then we can proceed in an orderly—’

‘Slavery?’ Steed broke in.

‘In a hundred years it will fall of its own weight.’

‘Have you read Hinton Helper?’

‘Yes, and I’ve read your retort.’

‘Which do you prefer?’

Again the gaunt reverend fell silent, finally mustering courage to say, ‘Helper. We’ll all be better off when slavery ends.’

‘I have close to a million dollars tied up in my slaves.’

‘Tied up

is the right phrase.’

‘Then why do you continue to give your sermons?’

‘Because we must all fight for time, Mr. Steed. We must keep things on an even balance, and believe me, having several million former slaves running free across the countryside will not maintain that balance.’

‘Answer me directly. Are the Quakers right? Should I free my slaves now.’

‘Absolutely not.’

‘When?’

‘In about forty years. Your son Mark seems a steady young man. He’ll want to free them, of that I’m sure.’

‘And my million dollars?’

‘Have you ever really had it? I preach often at Janney’s big plantation on the Rappahannock—’

‘Some of my forebears were Janneys.’

‘I think I heard that. Well, they’re supposed to have a million dollars, too. And they have difficulty finding a few coins to pay me. They’re rich, but they’re poor. And history has a way, from time to time, of shaking the apple tree, and the weak fruit falls off and the owner sees that he never had very many apples to begin with. Not really.’

‘Here you shall be paid,’ Steed said, producing a handfull of bills. ‘I find talking with you most refreshing. I can’t understand how you can preach the way you do.’

‘I’m an old man in an old tradition.’

‘You’re barely sixty!’

‘I go back to a different century. And I dread the one that’s coming.’

His sermon on Devon Island was by far the best of his tour, but it differed from the others because Paul and Susan Steed consented to sit in the shade only if he promised not to refer to them in any way. He therefore had to renounce his heroics and attend to his logic, and he made a stirring case for slavery as an orderly method of fulfilling God’s intentions. At Steed’s request he also stressed the duties of the master to the servant, quoting biblical verses he usually overlooked, but his peroration had the same fire as before, and when he ended, his listeners were in tears and some were shouting, and as he left the podium many blacks clustered around to tell him that he certainly knew how to preach. But as he moved toward the wharf, where a boat waited to deliver him to Virginia, he was accosted by two white people whom he had not noticed during his sermon. Somehow they had slipped into the edges of the crowd.

‘I’m Bartley Paxmore,’ the man said, extending his hand. ‘This is my wife Rachel.’

‘I’ve heard of you two,’ Buford said guardedly.

‘How could thee distort the word of God so callously?’ Bartley asked.

‘Good friends,’ Buford said without losing his temper, ‘we all need time, you as well as I. Are you prepared to bring down the holocaust?’

‘I would be ashamed to delay it on thy terms,’ Rachel said.

‘Then it will not be delayed,’ Buford said. ‘You’ll see to that.’ And he was so eager to escape the tangled passions of the Eastern Shore that he actually ran to his boat and jumped in.

When Elizabeth Paxmore, in her sickbed, heard Bartley’s report of Reverend Buford’s

Theft of Self,

she asked for her Bible and spent a long time leafing through it, sidetracked constantly by coming upon some passage she had memorized in her youth.

At last she cried, loud enough for everyone in the room to hear, ‘I’ve found it!’ And when her family gathered, even the grandchildren, who would remember this event well into the next century, she asked, ‘Why do they persist in censoring the one verse in the Bible that seems most relevant?’ And she read from Deuteronomy 23:15:

‘Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which is escaped from his master unto thee: … thou shalt not oppress him.’

She said that she wished her family to continue abetting the runaways, even if it took them away from Peace Cliff during what all knew was her last illness. ‘I will be able to fend,’ she assured them.

In 1859 two contradictory events provoked Paul Steed into sitting down and evaluating the economic base on which the Devon plantations rested. The first was the excitement aroused throughout America by the forceful book of a North Carolinian, Hinton Helper, who had the temerity to title it

The Impending Crisis,

as if slavery were in desperate trouble. In this uncompromising work Helper, a southerner with sound credentials, argued that the South must always suffer in competition with the North if it persisted in using slave rather than free labor. He marshaled statistics tending to prove that plantation owners would gain if they freed all their slaves, then hired the men back.

In Maryland the book caused a mighty stir, for these were the years men were choosing sides, and northern propagandists cited Helper to prove their claim that border states would be wise to stay with the Union. Legislation was passed making it a crime to circulate either Helper or

Uncle Tom’s Cabin,

and when the freed black who lived next to Cudjo Cater was caught reading a copy of the latter, he was sentenced to ten years in jail.

Many southerners wrote to Steed, reminding him that since his

Letters

had made him a champion of the slaveowners, he was obligated to rebut Helper; the petitioners argued: ‘We know that Helper has used erroneous facts to bolster his fallacious conclusions, and it’s your job to set the record straight.’

He would have preferred to avoid the fight, but a second event intervened, and this forced him to do precisely what his correspondents wanted: undertake to weigh dispassionately the pros and cons of the slave system. What happened was: Southern agriculture had suffered badly in the prolonged depression of the 1840s, and many plantations had neared collapse; it was this period that provided Helper with his statistics, and they certainly did prove that slavery was a burden; but starting in 1851 a veritable boom had developed, and in years like 1854 and 1856, southern

producers of tobacco, cotton, sugar, rice and indigo reaped fortunes.

Now the value of slaves increased; when Paul found it advisable to rent a few from neighbors, he discovered to his amazement that he must pay up to one dollar a day for their services, and provide food, clothing and medical supplies as well. During harvest the price jumped to a dollar-fifty, and he began to wonder whether returns from his crop warranted such outgo:

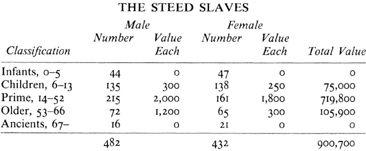

So I retired to my study and with all available figures before me tried soberly to calculate what the experience of the Steed plantations had been in bad years as well as good. I owned, at the beginning of 1857, a total of 914 slaves, distributed by age, sex and worth as follows:

Any slaveowner will quickly see that my figures are conservative, and I have kept them so on purpose. In this analysis I wish to offer the lowest possible value for my slaves and highest possible maintenance costs, for if under such circumstances they still produce a profit for the plantations, then slavery will have been demonstrated to be economically feasible. Therefore I should like to append a few notes to the above table:

Infants.

Obviously they are of considerable value, and to quote them as zero is ridiculous, but infants die, they become crippled, they prove themselves useless in other ways, so it is prudent to carry them on the plantation books at no proven value.Children.

Healthy children are bringing much higher prices these past few years than shown, especially those in the later ages. Were I so inclined, I could sell the Steed children south at prices considerably in advance of these, but at Steed’s we do not sell off our children.Prime.

Figures at Patamoke sales have been consistently higher than these, as proved by the rental prices in the past few years. If

an owner in Alabama can rent out a prime hand for up to $400 a year, and if the slave has forty good years, his actual value could be astronomical.Older.

These figures may be high. I could not sell our older slaves south for such prices, because they would not last long in the rice and sugar fields, but for what one might call domesticated service in a city like Baltimore, they could fetch even higher prices than I show.Ancients.

Every slaveowner will remember older Negroes who served handsomely into their eighties. Our plantation has a doorman who answers to the name of Tiberius who is one of the adornments of the island. Departing guests invariably praise him for his courtly style, and when visitors return to their homes their letters usually include some reference to Tiberius. If slaves have been well treated in their prime, they provide years of appreciated service in their seventies, but on the auction block they would bring nothing, so I list them at that.Artisans.

I do not include in my analysis any classification for the highly skilled mechanics who can contribute so much to the successful operation of a plantation. At Steeds we have perhaps two dozen men who would bring more than $3,500 each if offered for sale, and three or four who would fetch twice that. The plantation manager is slothful if he does not ensure the constant development of such hands within his slave force, for to purchase them on the open market is expensive when not impossible.So the value of the Steed slaves is over nine hundred thousand dollars, using the most conservative figures, and something like one and a quarter million with top evaluations. But what does this figure really mean? Could I go out tomorrow and realize nine hundred thousand dollars from the sale of my slaves? Certainly not. To place so many on the auction block at Patamoke would destroy all values; what I really have in my slaves is not a million dollars, but the opportunity to earn from their labor a return of about thirteen percent per year.

Warfare uses a concept of value which covers this situation,

the fleet in being.

Such a fleet is not actually at sea, and it is not fully armed or manned, and no one knows its exact condition, but in all his planning the enemy must take it into account, because the ships do exist and they might at any time coalesce into a real fleet. As they stand scattered and wounded they are not a fleet, but they are a fleet in being. My 914 slaves are wealth in being, and it often occurs to

me that they own me rather than that I own them, for as I have shown, I cannot sell them. Indeed, it is possible that the Steed family will never realize the nine hundred thousand dollars existing in these slaves; all we can do is work them well and earn a good yearly profit from that work. Thirteen percent of nine hundred thousand dollars is a yearly income of $117,000. Now I confess that rarely do we accomplish that goal, but we do well.