Chicken Soup for the Grandma's Soul (25 page)

Leo Tolstoy

“Dig in the dirt with me, Noni.”

My three-year-old grandson, Ethan, stood in the kitchen with pleading eyes and a big spoon. I had two large clay pots with soil that needed changing, and he needed something to doâa perfect match. After getting the necessary digging utensil from the junk drawer, he'd rushed to the deck and sent dirt flying everywhere. I could just imagine my daughter's reaction to his dirty clothes, but that was okay with me. As the grandma, I'm allowed to spoil.

It was hard to resist his invitation to play, but I had a meeting that night and I still had to fix supper.

“I can't right now, honey. Noni's busy.”

Ethan hung his head and stared at his shoes all the way back outside. Guilt hovered over me while I chopped celery and onions for meatloaf. Some grandma! But, I reasoned, it's different being a grandmother these days. I'm younger, busier. I don't have time to play like mine did when I was a child.

As I watched Ethan through the window, memories of a tea party with my grandmother surfaced. I remembered how Mammie filled my blue plastic teapot with coffee-milk and served toasted pound cake slathered in butter. She carried the tray as we walked to the patio and sat under the old magnolia tree that was full of fragrant, creamy-white blooms. I served the cake, poured the coffee into tiny plastic cups and stirred with an even tinier spoon. Our playtime probably lasted less than thirty minutes, and yet, after all these years, I still remembered.

Ethan saw me watching him and pointed to the pot. He had emptied it. I waved and nodded to him. Just then it dawned on me that my love for flowers came from Mammie. She had dug in the dirt with me. I recalled the new bag of potting soil and flower seeds I had in the garage. It would be fun to plant seeds and watch them grow with my little grandson.

I left my knife on the chopping block, found another old spoon and went outside.

“Noni can play now.”

Ethan clapped his dirty hands as I plopped down beside him. What fun we had that sunny afternoon. Supper was on time, and so was I for my meeting.

I learned the important life secret that Mammie always knew: there's always time to play.

Linda Apple

H

e that will make a good use of any part of his

life must allow a large part of it to recreation.

John Locke

She is a study in consternation. Hannah's brow is furrowed; she is squinting and biting her lower lip, sure signs of anxiety in this granddaughter.

The woeful mood is due to a second-grade scourge known as “homework.”

Hannah has begged to play outside on this glorious day, but I am under strict orders from her mother that she must first attack her assignments. And as the babysitter-in-residence, I am pledged to follow instructions.

Never mind that I, a former teacher, have decidedly mixed feelings about the importance of missing a golden afternoon when the sun is winking off the back patio, the trees are dancing in a lovely breeze and nature herself is celebrating spring.

Hannah's work sheets are spread out in front of her. It's been a while since I've seen what second-grade homework looks like, so I sit near Hannah, careful not to disturb her, but fascinated by watching this child I love so much as she attacks word configurations on a printed page.

Her teacher wants Hannah to transpose some letters to make new words. Hannah is working on set number threeâand has been at this for nearly twenty minutes. She had sailed through the first two setsâthe easy ones, she'd assured meâbut this third set was the killer.

So we sit together, a grandmother and a grandchild, and neither of us speaks. Once, Hannah throws down her pencil in frustration. Another time, I think I see the start of a tear in her chocolately brown eyes.

“Let's take a break,” I attempt. I even offer to make her favorite apple/raisin treat, one that usually gets Hannah racing off to the kitchen with me. But this earnest child is resolute. “If I finish,” she reasons aloud, “I can go outside and play with Julia and Trevor.” And to make matters worse, we can hear their shouts and occasional laughter through the open window.

Minutes later, Hannah has symbolically climbed to the language arts mountaintop. The word work sheets are finished. Now only two pages of addition stand between Hannah and the great outdoors.

Once again, all goes swimmingly at the beginning of Hannah's math homework. The computations come so easily that she's lulled into eight-year-old cockiness. “These are SIMPLE!” she exults, almost offended, it would seem, at the lack of challenge.

But on the second math worksheet, toward the bottom of the page, Hannah collides with a tough set. And she has her comeuppance. No matter how she struggles, the instructionsâand thus the solutionsâelude her.

I feel a meltdown coming.

It's nearly five in the evening. Hannah has been up since six-thirty in the morning. She's put in a full day in school, including a play rehearsal that both delighted and drained her. Her little brother is on a play-date, and he doesn't have homework because Zay is, after all, only in prekindergarten.

The injustice of it all finally gets those tears spilling. “I HATE homework,” Hannah sobs. And she means it.

This time, I ignore my pledges to her mother. I make an executive decision that my granddaughter and I are going outside to catch the lastâand hopefully bestâof this gift of a day.

For the next hour, I watch Hannah as she celebrates liberation. She runs and leaps and then climbs to the top of the jungle gym that is in the yard. I snap a photo of her as she performs feats of daring up there that still make me gasp.

Her cheeks are flushed, her hair is wild, and I wish that utter abandon and unbridled joy could last forever.

When my daughter comes home, Hannah is momentarily stricken. “I didn't finish my math sheets,” she confesses at once.

I hold my breath. I watch my daughter as she looks at Hannah, at me, and at the day that is surrendering to dusk.

And Jill says the very thing I might have written in a script for her:

“You can finish your homework later,” my daughter tells hers. “Play some more!”

And on a glorious spring day, I silently bless my daughter for her wisdom.

Sally Friedman

I

have often thought what a melancholy world

this would be without children; and what an

inhumane world, without the aged.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

My granddaughter Lydia, who was five years old, was visiting her grandpa and me one spring day when we all decided to go for a walk, taking Missy, our dog, with us.

Since I have multiple sclerosis, my legs have taken on wheels to accommodate me; I use a three-wheel scooter. Nonetheless, I enjoy the sunshine and the adventure of getting out and about like the rest of the family.

Now Liddy, as we call her, was taking in all her eyes would allow. As you may know, the eyes of a child spot things an adult's eyes may never see. So it was on this particular day. In the subdivision where we live, there are no sidewalks; everyone goes for their daily walks strolling down the middle of the streets. There is a slight embankment along the road, and it is in one of these shallow ditches that she spotted it.

“Look, Grandma,” Liddy said eagerly.

I tried to muster enthusiasm for the little artificial flower that had somehow made its way into the drainage ditch. “Oh, that is nice, Liddy.”

She held it tenderly. “It's a beautiful bouquet. Isn't it?”

“Oh, yes.” I placed it in the basket on my scooter.

“I want to plant it when we get home,” she informed me.

I couldn't bring myself to tell her it would do no good to plant an artificial flower.

“I know how to plant flowers. I planted some at Grandma Carolyn's house.”

Grandma Carolyn was her grandma on her mother's side, and I never questioned her endeavors or abilities. After all, that grandmother was more able-bodied than me. Liddy spent more time there, staying overnight and bonding with her other grandma in a small rural community a few miles away. I was sure Grandma Carolyn had helped Liddy plant real flowers in her yard.

We continued on our walk, with the artificial flower surviving quite nicely in my basket. It sat there rather staunchly, as if it knew it had a mission.

As our home came into view, Liddy, too, had a mission. She was going to plant that flower.

“I can make it grow,” she told me confidently.

She reached into my basket as we arrived at our house. I thought to myself,

How am I going to tell this sweet little child

that this is a flower that will not grow when planted?

“Liddy, you know that is not a real flower; it's artificial.”

“I know,” she said without batting an eye.

She told me she needed a shovel, then she picked out a spot beside the front walk leading to our porch.

“Grandpa, would you get Liddy a big tablespoon?” I requested of Bill, my husband.

I was not going to quash our granddaughter's spirit or her faith. She was sure she knew how to dig a hole, plant that flower and make it grow. She was adamant in her abilities and in that plastic flower's ability to sprout into an even more beautiful bouquet. She felt capable of achieving her goals. I wasn't going to deter her.

Liddy planted and watered her flower, proudly showing her daddy when he came. She had placed it in a spot where it wouldn't be missed on her next arrival.

Several visits and a multitude of rainstorms later, on one of her stopovers, Liddy, with a dejected look on her face, informed me that her flower was dying despite her loyalty. I couldn't stand the disappointment she faced.

One day a few weeks later, Bill purchased some flowers to plant in our backyard. A light went on in my brain.

“Bill, take one of those flowers and plant it by the walk in the front yard were Liddy planted that artificial flower.”

On her next visit, Liddy's eyes sparkled when she saw the purple, flourishing flowers. Her faith was renewed. She continued to water that flower and care for it each time she came, declaring, “I told you I can grow flowers.”

Sometimes nature and children need a boost in achieving their intended objectives.

Sometimes we just need to give a child hope in her dreams.

Sometimes we adults need to be encouraged to have the faith of a child.

Sometimes we need to replace our artificial lives with the real thing.

Other times, we need to water our hopes and dreams with effort, determination and will, having patience until they grow into being.

Most times, a child can teach us a multitude of things about ourselves and about lifeâif we just look at life through the eyes of a child.

Betty King

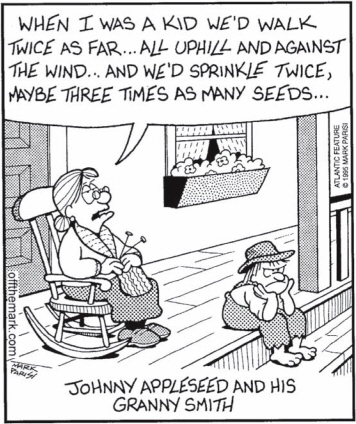

off the mark     Â

by Mark Parisi

Reprinted by permission of Mark Parisi. ©2005.

W

hat do we live for, if not to make life less difficult

to each other?

George Eliot

At the age of eighteen, I became the mother of not one baby boy, but two. Being an inexperienced mom frightened me. I had never even held a brand-new baby before. The day I left the hospital the nurse placed a baby in each arm. Equipped with two care packages filled with formula and baby wipes, off I went to face an adventure of a lifetime. At that time, I didn't realize the sacrifices I would make and how much of my time these two beautiful babies would require.

Instead of going home, my husband and I stayed with my parents for a couple of weeks.

The more help we can get,

the easier it will be,

I thought. Both of my parents worked during the day, so at night they were forced to get some much-needed rest. Sitting up most of the night with the boys as they took turns vying for my attention, then washing diapers while preparing formula during the day, was very exhausting, to say the least.