Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul (29 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Nurse's Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

As a new registered nurse, I’d been assigned to work evenings in an intensive-care unit in a small rural hospital. Back then, as now, staffing was short, and I was the only R.N. working that shift. It was a quiet evening with only five patients, all of whom were sleeping or resting. I told the two L.P.N.s to go grab some supper in the cafeteria and bring me back something to eat. Leaving me to cover the unit, they hightailed it out of there before I had time to rethink my lousy decision.

I pored over my paperwork, the rhythm of the beeping monitors playing their familiar tune in the background, when my nursing radar picked up an unusual noise that flagged my attention.

What the heck was that?

I looked up from my charts into the room across the hallway to see a cardiac patient standing beside his bed.

Hmmmm, not a good idea.

Then suddenly, before I could even complete that thought,

whoom!

His feet shot out from under him, his gown flew into the air, and he disappeared from sight!

Yikes!

I leaped from my chair, shot across the hallway, bolted through the door and into the room. As I made my dramatic entry, I spied a giant puddle of greenish brown fluid spreading across his floor.

Nursing diagnosis: greenish

brown liquid . . . body fluids . . . oh no! Poop!

Too late! I was already hydroplaning across the spillage, arms and legs flailing to keep me upright. Always the optimist, my mind raced ahead with positive thoughts:

I’m going to glide across this mess, land on both feet

and save the day!

This, unfortunately, did not happen. Instead, my feet skidded across the fluid and then,

whoom!

I landed so hard on my backside, my head bounced off the linoleum.

Ouch!

I shook the stars off and rolled over to look for my patient.

Spry thing that he was, he was trying to get up.

Boom!

He fell again. I tried to jump up to help him.

Wham!

I slipped again. He tried to pull himself up.

Whoom!

I scrambled for balance.

Wham!

With arms and legs splayed in every direction, we looked like Bambi and Thumper skidding on ice.

After what seemed an eternity, our eyes met, and I realized he was laughing. “It’s probably not what you think,” he said with a wink, and motioned to our putrid puddle. A Styrofoam cup lay tipped beside it.

Totally discombobulated, I couldn’t understand what he was trying to tell me. “Huh?”

He shook his head as if to apologize. “I was hoping to hide my tobacco juice before you made rounds.”

It took a minute to sink in.

Is this the good news or the bad

news? Tobacco juice or poop: Which would I rather be wrestling

around in?

To this day I’m still not sure. But once I knew that my patient was okay, I was able to see the humor in the situation, and we both enjoyed a good laugh together.

Lesson #1: Life’s curveballs, plus time, equals humor. If there’s a chance that you’ll be laughing about something later, try to shorten the time frame. Laugh about it sooner.

Lesson #2: It’s to your advantage if you can laugh at yourself before others do. By the time I walked out of that room with greenish brown slime painted all over my crisp white uniform, everyone else immediately saw the humor in the situation. Since I was already laughing, my colleagues laughed with me instead of at me!

Lesson #3: The closer you are to tragedy, the odder your humor becomes. Nurses have to be able to laugh at some of the tough stuff or we burn out and leave this wonderful profession.

Nurses can find the silver lining and the humor in the most bizarre places—thank God!

Karyn Buxman

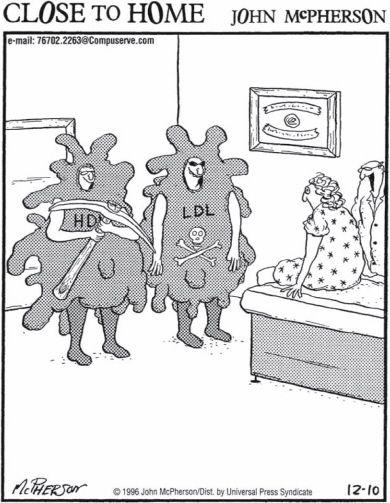

“To help you better understand this good cholesterol/ bad cholesterol thing, Nurse Bowman and Nurse Strickling are going to do a little skit for you.”

CLOSE TO HOME

© John McPherson. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS

SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

A

sssuredly I say to you, unless you are converted

and become as little children, you will by

no means enter the kingdom of heaven.

Matthew 18:3

I have been a nurse for twenty-three years in various areas of nursing, but the story of this child, who I will call “Tommy,” has always haunted me.

I worked in a temporary shelter for abused and neglected children, ages birth through seventeen years. I sat on the floor in the lobby listening to the sketchy information the police officer provided. Tommy hid behind the officer, only cautiously poking his head out every once in a while when he heard his name spoken. He gripped the policeman’s finger with one hand and held a raggedy stuffed bear with the other.

I opened a bottle of bubbles and blew them in the air around me, all the while watching Tommy out of the corner of my eye. Slowly, he peered from behind the police officer to watch bubbles cascade through the air and silently pop on the carpet. Tommy took two small steps, but still held on to the officer’s finger. He looked up at the adults standing by him and seemed surprised that no one noticed he had moved. He let go of the officer’s finger and hugged the raggedy bear to his chest with both hands. Stealthily, he walked across the room and knelt down about three feet from me. His face was upturned as he focused on the bubbles floating in the air.

This was my first chance to assess his physical condition. I knew his trust in me was only a temporary truce while he remained fascinated with the bubbles.

Tommy’s bright red cheeks were smudged with dirt and stained from tears. I realized this redness on his cheeks was the shape and size of a hand—angry welts slowly rising in the form of fingers. His left eye, almost swollen shut, was discolored red and purple. The other eye, big and brown, lined with long, dark lashes, was still intent on the bubbles. There was a freshly scabbed cut below his cracked and edematous lower lip. A crusted, linear abrasion encircled his neck. As Tommy reached to catch a bubble before it hit the floor, I noticed a small circular blister on the palm of his right hand, evidence of a burn likely made from a cigarette.

I sat silently with Tommy and the bubbles, trying not to show the emotions I felt for what he must have suffered and the anger I had for the man who had done this to him. The rest of the assessment would have to be done when his clothes were removed for a bath and Tommy was not ready for that.

Shyly, in a voice barely above a whisper, he asked to blow the bubbles. Soon the room was filled with them floating in the air and Tommy laughing at the simple joy of this game, everything and everyone else temporarily forgotten.

The police officer came and knelt on one knee by Tommy and told him he had to leave. He pinned a toy badge to Tommy’s shirt and said Tommy was an honorary sergeant because he was such a brave man today. I watched Tommy stiffen and grow silent once again. His eyes glistened with tears as the police officer shook his hand.

Tommy threw his arms tightly around the officer’s neck, the bubbles forgotten. He said, “Tell Daddy I love him.”

Rebecca Skowronski

THE FAMILY CIRCUS

By Bill Keane

“She’s listening to PJ’s heartbeep.”

Reprinted with permission from Bil Keane.

T

he tones of human voices are mightier than

strings or brass to move the soul.

Friedrich Klopstoch

At 3:00

P.M

., the young nurse looked up from her charting at the nurse’s station to see the emergency room orderly wheel her admission into room 107. She had hoped to finish her charting and dictate report before he arrived.

And

she still needed a final set of vitals on her post-op tonsillectomy.

And

the ice packs needed to be replaced on the knee in 104. It’s a good thing she’d set the room up earlier. She was ready for the admission—bed linens turned down, water pitcher filled, pediatric nightgown on the bed.

The nurse scribbled her signature on her unfinished charting and hustled to 107 to greet her patient. The ER phone report said six-year-old Joey had been removed from a violent home situation that afternoon and was being admitted for evaluation of injuries resulting from physical abuse. She was relieved to see the little boy walk from the wheelchair to the edge of the bed. That was a good sign—his injuries didn’t seem severe.

The nurse bent to Joey’s eye level and smiled. “Welcome to pediatrics, Joey. We’re going to take really good care of you here.” The small boy forced an uncertain smile.

“I have a few things I have to finish up real quick, then I’ll be back to get you all settled in.” Joey sat stiffly on the edge of the mattress, his hands folded in his lap. The young nurse reassured him with another smile. “It won’t be long.” With that she rushed out of the room, and so did the orderly—but not before handing her two pages of orders from Joey’s doctor. X ray STAT . . . lab work STAT.

At the nurse’s station, she dialed X ray with one hand while filling out pharmacy requisitions with the other. The charge nurse walked in. “Did you see your admission is here in 107?”

The young nurse took a deep breath. “Yes, I saw him. But until I get the X rays ordered, the drugs from pharmacy and the supplies from central service, I can’t take care of him, can I?” She smiled weakly. “And I still have post-op vitals due in 110 and an end-of-shift report to dictate.”

The charge nurse said, “I’ll check the post-op vitals. You can give oral report later. Right now, prioritize and just do what’s most important first.”

The young nurse held the phone receiver to her ear with her shoulder and dialed the lab, while stamping central service requisitions. That’s when her colleague handed her the other phone. “It’s admissions. They say there’s a discrepancy about the age of your new patient in 107. The social service form says he’s six and the police report says he’s five.”

The nurse groaned. “I’ll ask Joey when I admit him.”

“They say they can’t complete the admission, which means they can’t fill the doctor’s orders, until they know.”

The young nurse heaved a sigh and pushed the intercom button.

“Joey?”

He didn’t answer.

“Joey?”

Silence.