Children Of The Poor Clares

Read Children Of The Poor Clares Online

Authors: Mavis Arnold,Heather Laskey

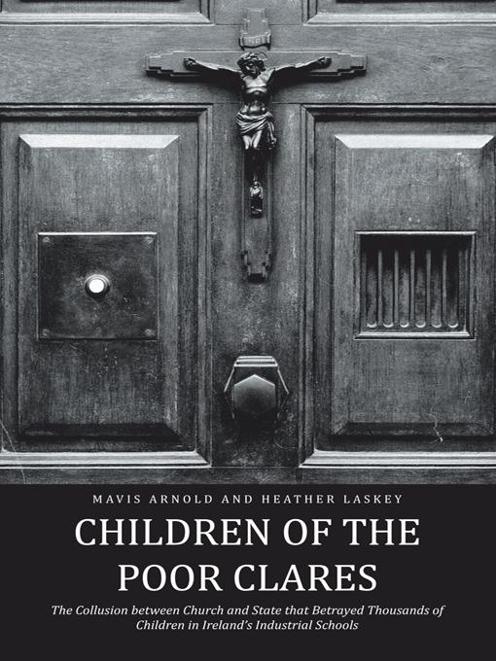

CHILDREN OF THE POOR CLARES

REVISED UPDATED VERSION

The Collusion between Church and State that

Betrayed Thousands of Children in Ireland’s Industrial Schools.

BY MAVIS

ARNOLD AND HEATHER LASKEY

Order this book online at

www.trafford.com

or email

[email protected]

Most Trafford titles are also available at major online book retailers.

© Copyright 2012 Mavis Arnold and Heather Laskey.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

The original edition of ‘Children of the Poor Clares: The Story of an Irish Orphanage’ from

which this present book has been extensively revised, extended and updated, was first published and printed by The Appletree Press Ltd., Belfast, N. Ireland, in 1985.

This book was created in the United States of America.

isbn:

978-1-4669-0903-8 (e)

Trafford rev. 01/18/2012

North America & international

toll-free: 1 888 232 4444 (USA & Canada)

phone: 250 383 6864.♦.fax: 812 355 4082

Contents

The authors wish to thank the many people we interviewed, and without whom this book could not have been written. In particular we thank all the ex-pupils who told us their stories of their lives both inside these institutions and in the outside world.

The names of all ex-pupils of Industrial Schools and inmates of other institutions that we interviewed or heard about have been changed to guard their privacy; also the names of other non-public figures either at their request or to maintain their privacy. This also applies to nuns, unless we knew they were dead or where they made public statements. Exceptions are also made to this rule of privacy in the case of ex-pupils where they made public statements or have written books, or were publicly identified—as in the case of the orphanage fire and Inquiry.

For

Anne

and

all

the

others

“It shall be the First Duty of the Republic to make provision for the physical, mental and spiritual well-being of the children.”

Declaration of the Provisional Dail of 1919.

Bruce Arnold

I was an onlooker to the events that gave birth to this book. I knew the authors when we were all students and married one of them. Our children grew up knowing one of the principal characters; we know much of her life story, and that of her children and grandchildren. All of them have been marked by the dire ineptitude of the supposed care and charity bestowed on her by the Order of the Poor Clares.

When the events covered in the early chapters of this book were revealed to us, bit by bit, their chilling message was deeply impregnated with a sense of isolation and secrecy. We knew what had happened to her and to other members of her family, and we knew the story of others whose childhood life she had shared. What we did not know was the extent to which the experiences of the young girls in St Joseph’s Orphanage in Cavan town represented a tiny part of a system that was spread throughout the length and breadth of the country. Thousands of children were incarcerated over many decades. They were given what were in effect long prison sentences by the courts under legislation that was severely interpreted and even more severely backed up by the Church, the social workers who were supposedly caring for young deprived and disadvantaged children. Those committed to the industrial school and orphanage system had one thing in common: the period of their confinement ended, usually, at age sixteen. Some had been in institutional care since they were infants.

This book researched into other aspects that also had a common character of a very unhappy and, from the State’s point of view, shameful background. Almost universally throughout the industrial school system—which, at its most extensive, had several thousand boys and girls in what would now be called “care”—the administration of the children’s needs was seriously defective. They were always hungry, malnourished, and in some cases they literally starved. It has been said by the religious orders which managed these places that “times were hard”. This was emphasised in the context of times being hard generally in the country, through poverty, from the 1930s to the 1960s. It was not so. The State’s subvention, on a

per

capita

basis, was adequate to feed, clothe, house, heat and give health care to the inmates. It also provided sufficient for educational and craft skills to be taught.

It was rarely done. There were exceptions, but they prove the rule that in reality the money disappeared. Startling tales are told by men and women who went through the system of the loaded tables of the religious, the disposal of waste to pig farms, while the children remained hungry. One of the worst examples has been published. This was the Baltimore School in Cork. It came directly under the Bishop of Ross, now dead, and it was examined in horrifying detail by Judge Mary Laffoy, head of the Commission to Investigate Child Abuse. Children who had serious eye defects so that they could not follow the limited teaching they got but never saw an optician. They did not possess toothbrushes. They were never seen by a dentist. They slept on foul bedding and contracted diseases from vermin. Their education, seriously inadequate, equipped them only for the most menial of jobs. And there is evidence that this led to further abuse and also to exploitation of a brutal and horrifying kind.

St Joseph’s was not the worst, not even among the worst. Yet the collected testimony indicates a regime that was profoundly ignorant of the needs of the girls, cruel towards them to the point of sadism, and dishonest in the presentation of their plight to the outside world.

People now say that everyone knew about it. Yet at the time no one spoke out. The iron hand of the Church kept the voices of witnesses silent. This was even so when St Joseph’s was plunged into the limelight by the tragic fire which is part of this book’s story. In it many girls died, clearly unnecessarily. The State and the administration of St Joseph’s, with the Church conniving, covered up the nature of the institution and the degree of ignorance and lack of intelligent action that led to the deaths. The Report was a whitewash.

It took the indirect intervention of a European organisation, the O.E.C.D. (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) investigating Irish education with a view to assessing Ireland’s credentials for entry into the European Union, to wake the country up to what was going on. That organisation, spotting the anomaly in education levels in the industrial schools, blew a whistle to which the then Minister of Education, Donagh O’Malley, responded. As a result, through the Kennedy Committee which he set up, the dismantling of the whole system was mercifully started.

It took six years before the original 1985 edition of this book could find a publisher. In the following years, a changed climate of outspokenness in the country as a whole led to further revelations and to television documentaries that exercised a powerful impact on the public and on the politicians. It achieved far less with the Church.

Nevertheless, with his apology in 1999, the Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, changed the tempo and direction of blame and anguish. He acknowledged “a collective failure to intervene, to detect their pain, to come to their rescue”. He made what he called a sincere and long overdue apology, and he set in motion legislative remedies.

I have never been happy with the apology and what followed. On investigation I was able to reveal, in a number of newspaper articles, what I call, rather guardedly, a hidden agenda. There was clear evidence of collaboration between Church and State. Collectively, the State, through the Department of Education, and C.O.R.I.—Conference of Religious of Ireland—acting on behalf of the orders, sought to create a self-protective structure. It included the agreement. The Government backed this with laws, procedures and investigations. The order was protected in exchange for their acceptance of the other processes which appeared to fulfil the terms of the apology by the Taoiseach.

The system of Redress was unfair and, again, secretive. Men and women seeking recompense were under legal restraint not to divulge the amounts given to them. There were heavy penalties for breaching these conditions. The alternative route to compensation—through the courts—was made peculiarly difficult. The terms under which the religious communities were persuaded to come forward protected them, in law, from criminal prosecution. This was an unusual exclusion in Irish tribunal law.

From the outset, the set of proposals that were offered—in that suspect phrase—to “bring closure”—have instead brought suspicion, distrust, dismay and disappointment to the victims. They still feel on the outside. They still feel that their circumstances—as diminished, marginal, second class people in Irish society—remain unchanged.

This applies to the girls of St Joseph’s as much as to the rest of them. And it is wrong.

When

Children

of

the

Poor

Clares

first appeared I was immensely proud of what my wife and our friend, Heather Laskey, had achieved. It had the simple appeal of what I saw as careful, objective truth. It was and is a poignant picture of a dark set of experiences that paint a terrible picture of a hidden Ireland, brutal, cruel and covert. This much-revised, updated and extended version enriches the story and adds greatly to our knowledge of what has happened since in an ongoing saga. But it still leaves the story unfinished. It will never be finished. The pain and damage to these men and women, many of whom have long since passed on, many of whom are still wrestling with the memories and the nightmares, are a shameful extract from living history. The State still has not dealt with them fairly. It has not drawn them in nor healed their suffering. And anyone who thinks otherwise has only to take up this book and read the truth.