Chinese Fairy Tales and Fantasies (Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library) (20 page)

Read Chinese Fairy Tales and Fantasies (Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library) Online

Authors: Moss Roberts

Today in the eastern land of the Chieh tribe, the people have a

special gift for understanding the speech of domesticated animals. But the sacred sages of ancient times knew all there was to know about the natures of things. They understood the cries and calls of different species, gathered them in assembly, and taught them as if they were people. Indeed, first the sages would bring together the spirits of the dead and other demons, next they would gather the peoples of the eight outlying directions, lastly they would assemble the beasts and insects for their lessons. This shows that all species which have blood and breath do not differ much in their hearts and minds. The holy sages knew this well, and that is why they taught all and left none out.

—

Lieh Tzu

The Fish Rejoice

Chuang Tzu and his close friend Hui Tzu were out enjoying each other’s company on the shores of the Hao. Chuang Tzu said, “The flashing fish are out enjoying each other, too, swimming gracefully this way and that. Such is their joy!”

“You’re no fish,” said Hui Tzu. “How can you tell they are enjoying themselves?”

“You’re no Chuang Tzu,” said Chuang Tzu. “How can you tell I can’t tell?”

“As surely as ‘I’m no Chuang Tzu’ proves

I

can’t tell,” said Hui Tzu, “ ‘You’re no fish’ proves

you

can’t tell. It’s perfectly logical.”

“May we begin at the beginning?” returned Chuang Tzu. “By asking ‘How can you tell the fish are enjoying themselves?’ you acknowledged I could tell you! And what’s more I can do it from up here!”

—

Chuang Tzu

Wagging My Tail in the Mud

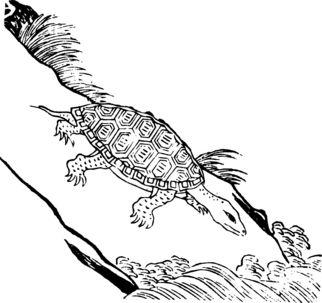

The hermit poet Chuang Tzu was angling in the River Pu. The king of Ch’u sent two noblemen to invite Chuang to come before him. “We were hoping you would take on certain affairs of state,” they said. Holding his pole steady and without looking at them, Chuang Tzu said, “I hear Ch’u has a sacred tortoise that has been dead three thousand years, and the king has it enshrined in a cushioned box in the ancestral hall. Do you think the tortoise would be happier wagging his tail in the mud than having his shell honored?” “Of course,” replied the two noblemen. “Then begone,” said Chuang Tzu. “I mean to keep wagging mine in the mud.”

—

Chuang Tzu

WOMEN AND WIVES

Li Chi Slays the Serpent

In Fukien, in the ancient state of Yüeh, stands the Yung mountain range, whose peaks sometimes reach a height of many miles. To the northwest there is a cleft in the mountains once inhabited by a giant serpent seventy or eighty feet long and wider than the span of ten hands. It kept the local people in a state of constant terror and had already killed many commandants from the capital city and many magistrates and officers of nearby towns. Offerings of oxen and sheep did not appease the monster. By entering men’s dreams and making its wishes known through mediums, it demanded young girls of twelve or thirteen to feast on.

Helpless, the commandant and the magistrates selected daughters of bondmaids or criminals and kept them until the appointed dates. One day in the eighth month of every year, they would deliver a girl to the mouth of the monster’s cave, and the serpent would come out and swallow the victim. This continued for nine years until nine girls had been devoured.

In the tenth year the officials had again begun to look for a girl to hold in readiness for the appointed time. A man of Chianglo county, Li Tan, had raised six daughters and no sons. Chi, his youngest girl, responded to the search for a victim by volunteering. Her parents refused to allow it, but she said, “Dear parents, you have no one to depend on, for having brought forth six daughters and not a single son, it is as if you were childless. I could never compare with Ti Jung of the Han Dynasty, who offered herself as a bondmaid to the emperor in exchange for her father’s life. I cannot take care of you in your old age; I only waste your good food and clothes. Since I’m no use to you alive, why shouldn’t I give up my life a little sooner? What could be wrong in selling me to gain a bit of money for yourselves?” But the father and mother loved her too much to consent, so she went in secret.

The volunteer then asked the authorities for a sharp sword and a snake-hunting dog. When the appointed day of the eighth month arrived, she seated herself in the temple, clutching the sword and leading the dog. First she took several pecks of rice balls moistened with malt sugar and placed them at the mouth of the serpent’s cave.

The serpent appeared. Its head was as large as a rice barrel; its eyes were like mirrors two feet across. Smelling the fragrance of the rice balls, it opened its mouth to eat them. Then Li Chi unleashed the snake-hunting dog, which bit hard into the serpent. Li Chi herself came up from behind and scored the serpent with several deep cuts. The wounds hurt so terribly that the monster leaped into the open and died.

Li Chi went into the serpent’s cave and recovered the skulls of the nine victims. She sighed as she brought them out, saying, “For your timidity you were devoured. How pitiful!” Slowly she made her way homeward.

The king of Yüeh learned of these events and made Li Chi his queen. He appointed her father magistrate of Chiang Lo county, and her mother and elder sisters were given riches. From that time forth, the district was free of monsters. Ballads celebrating Li Chi survive to this day.

—

Kan Pao

The Black General

Kuo Yüan-chen, who later became the lord of Tai, failed the official examination during the K’ai Yuan era (

A.D

. 713-742). Afterwards, while traveling, he lost his way in the night. A good while later he saw the rays of a light far, far away, and assuming that it was a dwelling, headed toward it.

He rode some three miles until he reached a tall and imposing structure. In the corridors and the main hall, lanterns and candles were blazing brightly as he entered. Delicacies and sacrificial meats were laid out as in the home of a family whose daughter was to wed. Yet it was silent and deserted.