Chinese Fairy Tales and Fantasies (Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library) (34 page)

Read Chinese Fairy Tales and Fantasies (Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library) Online

Authors: Moss Roberts

Next day Wang Mien’s mother went with him to their neighbors, the Ch’in family. Old Ch’in had them stay for breakfast and then led out a water buffalo, which he turned over to Wang Mien. The farmer pointed beyond his gate and said, “Just a couple of bowshots from here you’ll find Seven Lakes. Along the lake runs a stretch of green grass where the buffalo of all the families doze. There are dozens of good-sized willows that give plenty of shade. When the buffalo get thirsty, they can drink at the lakeside. Enjoy yourself there, young fellow; no need to go far. And you’ll never get less than two meals a day, plus the bit of cash I can spare you. But you must work hard. I hope my offer isn’t disappointing.”

After making her apologies, Wang Mien’s mother turned to go, and her son escorted her out the gate. Giving his clothes a last

straightening, she said, “You must be very careful here. Don’t give anyone cause to find fault with you. Go out at daybreak and get home by nightfall, and spare me any worry.” Wang Mien said he understood, and his mother left, holding back her tears.

From that time Wang Mien spent his days tending the Ch’in family’s buffalo. At dusk he would return to his own home for the night. There were times when the Ch’ins offered him a little salted fish or preserved meat, and without fail he would wrap it in a lotus leaf and take it home to his mother. As for the few coppers he was given for snacks, he always saved them up for a month or two. Then he would steal a free moment to go to the village school and buy a few books from the bookseller there. Every day after tethering the buffalo, he would sit and read beneath the willows.

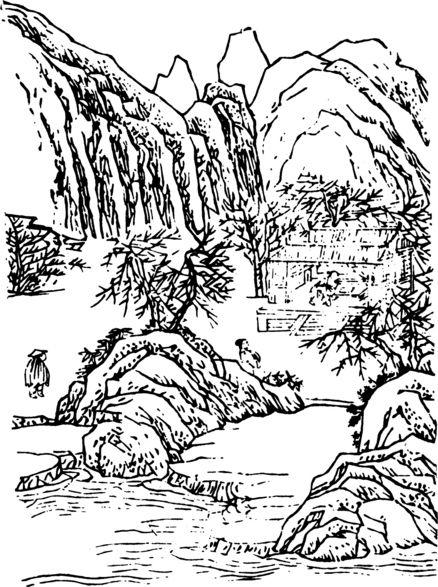

Another three or four years sped by. Wang Mien kept studying and began to see the real meaning of what he read. On one of the hottest days of midsummer when the weather was unbearable, Wang Mien was idling on the grass, tired out from tending the buffalo. Suddenly dense clouds spread across the sky. A storm came and went. Then the dark clouds fringed with white began to break, letting through a stream of sunshine that set the whole lake aglow. The hills above the lake were masses of green, blue, and purple; the trees, freshly bathed, showed their loveliest green. In the lake itself, clear water dripped from dozens of lotus buds, and beads like pearls rolled back and forth over the lotus leaves.

Wang Mien took in the scene. “Men of olden times said that man is in the picture,” he thought. “How true! If only we had a painter with us to do a few branches of these lotuses—how fascinating it would be!” At the same time it occurred to Wang Mien: “There’s nothing in the world that can’t be mastered. Why not paint a few myself!”

While entertaining these daydreams, what did Wang Mien see in the distance but a clumsy porter shouldering a load of food suspended from a pole and carrying a jug of wine in his hand. A mat was draped over the packages of food. When he arrived under the willows, he spread the mat and opened up the packages. From the same direction three men were approaching who wore scholars’ mortarboards on their heads. One of them was dressed in the sapphire-blue robe of a degree holder, the other two simply in dark robes. All three appeared to be forty or fifty years old. They advanced with leisurely step, fanning themselves with white paper fans.

The one in blue was a fat man. When he arrived beneath the willows he showed one of his companions, who had a beard, to the place of honor and the other, a skinny man, to a place opposite. The fat man must have been the host, for he took the lowest seat and poured the wine. After they had spent some time eating, the fat man opened his mouth to speak: “Old Master Wei is back! He just bought a new house. It’s even bigger than the one he had in the capital and cost two thousand taels of silver! Because Master Wei was the buyer, the owner lowered the price a few dozen taels for the sake of the prestige that would rub off on him. Master Wei moved into the house early last month. Their Honors, the governor and the county magistrate, came personally to his door to offer their congratulations and were entertained there until well into the night. The whole city holds him in the highest regard.”

“His Honor the county magistrate,” said the skinny man, “won his penultimate degree in the triennial examination. Master Wei was his examiner, hence his patron. So it was only to be expected that he would come to congratulate his patron.”

“My brother-in-law,” said the fat man, “is also Master Wei’s protégé. Now he’s a county magistrate in Honan province. Day before yesterday my son-in-law brought over a few pounds of dried venison. (There it is on the plate.) When he returns, I’m going to have him ask my brother-in-law to write a letter to introduce me to Master Wei. If Master Wei honors us with a return visit, our fields will be saved from the pigs and donkeys that our local farmers let loose to eat their fill.”

“Old Master Wei’s a true scholar!” said the skinny man.

“They say that when he left the capital a few days ago,” added the bearded man, “the emperor himself saw him out to the city wall, and then they walked about a dozen steps hand in hand. Master Wei had to bow down again and again declining the honor, before His Majesty returned to his sedan-chair. The way things look, Master Wei should soon be in office.” Thus the conversation went back and forth, never reaching an end. Wang Mien, however, saw that evening was approaching, so he hauled his charge home.

Now Wang Mien no longer put the money he saved into books. Instead he had someone buy him some pigments and white lead powder so that he could learn to paint the lotus. His first efforts were not especially good, but after a few months he could make a perfect likeness of the blossom both in outward appearance and essential quality. Had it not been for the sheet of paper they were on, his lotuses could be growing in the lake! Some local people who saw how well he painted even paid money for his work, and with it Wang bought a few treats for his mother.

Word spread until the whole county of Chuchi knew that there was among them a master of brushwork in the “boneless” or soft-shape style of flower painting. People began competing to buy the paintings. When Wang Mien reached the age of seventeen or eighteen, he was no longer working for the Ch’in family. Every day he would make a few sketches or study the ancient poets. As time went by he did not have to worry about food or clothing, and his mother was happy as could be.

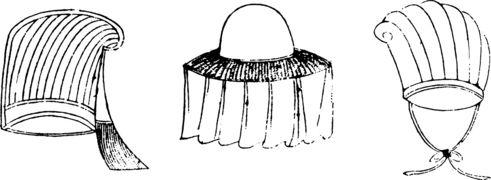

Wang Mien was so gifted that before he was twenty he had mastered such fields of knowledge as astronomy, geography, the classics, and the historical texts. But he was unusual in that he sought neither office nor friends; he remained secluded with his studies. When he saw illustrations of Ch’ü Yüan’s

*

costume in an edition of Ch’ü’s great poem “Li Sao,” Wang Mien fitted himself out with the same kind of tall tablet-like hat and billowing robe.

When the season of fair days arrived, he set his mother in a bullock cart, garbed himself after his newest fashion, and with a whip in his hand and a song on his lips, traveled around wherever

it pleased him—to the neighboring villages and towns or down to the lakeside. His jaunts excited the laughter of the village children, who tagged after him in little groups. Wang Mien did not care. Only Old Ch’in, his neighbor, loved and respected him, for though the old man was a farmer, he had a mind of his own and had seen Wang Mien grow from youth to cultivated maturity. Time and again the two enjoyed the warmest companionship when he invited Wang Mien to his cottage.

One day when Wang Mien was visiting with Old Ch’in, what did they see outside but a man coming toward them—a man wearing the conelike cap and black cotton of a lowly officer. Old Ch’in welcomed the visitor, and after mutual courtesies the two men sat down. The visitor’s surname was Chai, and he was serving the Chuchi county magistrate as chief sergeant and steward at the same time. Since the eldest of Old Ch’in’s sons was a ward of Steward Chai’s and called him Godfather, the steward frequently came down to the village to visit his relative.

Old Ch’in made a big fuss and told his son to brew tea, kill a chicken, and cook up some meat to entertain Chai in grand style. Then he asked Wang Mien to join them. After Old Ch’in introduced Wang Mien to his guest, Steward Chai said, “Can this honorable Mr. Wang be the expert painter of flowers in the soft-shape style?”

“The very man himself,” replied Old Ch’in. “But my dear relative, however did you know?”

“Who around town doesn’t?” said the steward. “A few days ago His Honor, our county magistrate, told me he wants a folio of twenty-four flower paintings to send to

his

superior and turned the job over to me. People speak so highly of Wang Mien that I came especially to you, dear relative. And now fortune enables me to meet Mr. Wang, whom I would trouble for a few strokes of his honored brush. In a fortnight I shall return here to fetch them. I am sure His Honor will have a few taels of silver to ‘moisten the brush’; I’ll be bringing them along.”

From the sidelines Old Ch’in was earnestly prodding Wang Mien who, rather than hurt Old Ch’in’s feelings, had no choice but to accept. He went home and threw himself into the composition of the twenty-four floral pieces, adding a poem to each. The steward Chai reported to his office, and the magistrate Shih Jen paid out twenty-four taels of silver. The steward took twelve taels for his commission, delivered twelve to Wang Mien and left

with the folio. The magistrate took the folio from the steward and assembled a few other gifts for Mr. Wei to wish him well.

Wei Su was interested in none of the gifts except the folio. He cherished it, savored it, would not let it out of his hands. The next day he invited Magistrate Shih to a banquet at his home to express his thanks. And there they passed the time of day as the wine went round.

“A day ago I received the flower album Your Honor so kindly sent,” said Wei Su. “I wonder, is it the work of some classic master or a man of our own times?”

The magistrate could hardly keep the truth from his superior. “The painter is a local peasant from your protégé’s district. His name is Wang Mien, and he is quite young—just a beginner. He hardly deserves to come within your discerning view, dear patron.”

“Humble student that I am,” said Wei Su with a sigh, “I have been away so long that I am guilty of ignorance that so worthy a talent has come from my home village. A shame. A shame. This good fellow has not only the highest skill but a wealth of knowledge. Most unusual! He will equal us one day in name and in position, too. Could you arrange for me to meet with him, I wonder?”

“No problem,” replied the magistrate. “When I leave I shall have someone arrange it. When Wang Mien learns that it is my dear patron who takes such an interest in him, I know he will be beside himself with delight.” And with that he bid adieu to Wei Su, returned to his office, and assigned the steward Chai to invite Wang Mien in the humblest and most courteous form to a meeting with Wei Su.

The steward fairly flew to the village and went straight to the home of Old Ch’in to present the invitation. And if he presented it to Wang Mien five times, he presented it to him ten times, but Wang Mien only laughed and said, “I’m sorry, but I shall have to trouble you, Steward, to report back to His Honor that Wang Mien is a mere peasant who would never dream of such an audience. Nor would I dream of accepting this invitation.”

The steward’s face darkened as he said, “Who would dare refuse His Honor’s invitation? Not to mention the fact that if I myself hadn’t done you the favor, His Honor would never have known of your talent. It stands to reason that after meeting His Honor, you should find a way to show me your gratitude. And

what’s the idea of not putting out a cup of tea for me after I’ve come all this way? And giving me this excuse and that for being unwilling to go—what’s it supposed to mean? And how am I supposed to make a proper report to His Honor? Are you trying to tell me that the head of a whole county can’t summon a commoner?”

“Steward,” said Wang Mien, “there’s something you don’t understand. If I had done something wrong and His Honor issued an official summons for my appearance, how could I refuse? But this is only an invitation, which means he’s not

demanding

that I go. I’d rather not go. His Honor should forgive me!”