Choose Yourself! (21 page)

Authors: James Altucher

Tags: #BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS / Entrepreneurship, #SELF-HELP / Personal Growth / Success

Ten years later I ran into the employee who became CEO of that spinoff company. He ran after me and called my name. It was in Times Square in New York. We hadn’t spoken in almost ten years. His company had greatly expanded. They had taken in major investors, and the company was now profitable and had lots of employees. He told me that when he walked the floor, he always pictured two people as his role models: his commander in the Israeli Army. And me. I felt really honored. He had greatly helped me when I was building my business. And now it was an honor for me to help him back in that way. I don’t ever have to benefit off of his business. But his business is helping many people now and, in its own way, that creates abundance for me. The abundance can never stop when you help others.

I haven’t always been honest. I try. And I hope I’m getting better. I try every day to improve and to follow the advice I’ve just given you. Otherwise I wouldn’t have given it. But I’ve seen it. With people who have been in business for ten, twenty, forty years. Honesty compounds little by little. And that compounding turns into millions or billions. The dishonest people disappear. They die. They go to jail. They don’t maximize their potential. They run. They are scared.

You will have nobody to run from. Some people will hate you. Some people will doubt your sincerity. But the people who need someone to call, someone to share with, or someone to give to, these people will know who to call. They will call you.

YOU’RE NEVER TOO YOUNG TO CHOOSE YOURSELF: NINE LESSONS FROM ALEX DAY

I wish I had been smarter when I was twenty-three years old. I did everything wrong: I felt like I needed a college degree. I felt like I needed a graduate degree (I was ultimately thrown out of graduate school). I felt like I needed a publishing company to “choose me” to be a writer. I felt like I needed a big corporation to hire me so I could validate that I was smart, that it was okay for me to be successful.

I needed none of these things.

You need none of these things.

The world has changed, become different. The middleman is on life support, the barriers to entry have come down, and the Choose Yourself era has fully arrived.

Alex Day

is a perfect example. If you’ve never heard of Alex Day, that’s okay. Most people haven’t. But enough have. And they LOVE him. Alex is a twenty-three-year-old musician from England. Since 2009, when he was nineteen, he’s released three studio albums, had three UK Top40 hits, and accrued 100-plus million views on his YouTube channel. He did

all of it

with no record label and mostly just the support of his YouTube fans. His third, most recent album came out in the UK the same day as Justin Timberlake’s long-awaited, much-discussed

20/20 Experience

album (his third, also).

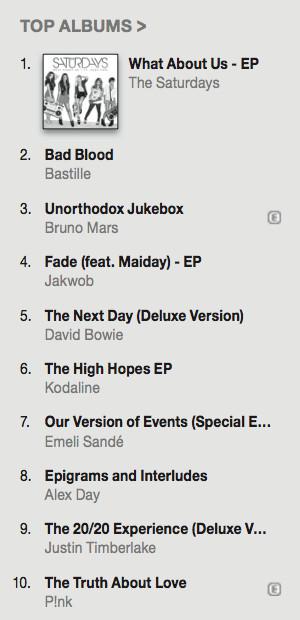

Here’s the result:

Snapshot of the itunes chart the day after both albums were released

Justin Timberlake is like the crown prince of the music industry. The labels love him. The radios love him. He tours everywhere. He has a massive marketing machine behind him. And he’s married to Jessica Biel. That’s all pretty good.

But not enough. Alex Day beat him. How the hell did that happen? I had no idea. So I called up Alex and asked him.

Lesson Number One about Choosing Yourself: I can choose myself to call anyone I want.

If they want to talk to me, great.

Here is my interview with Alex, re-printed in its entirety (it’s got too much good stuff just to excerpt):

Me: I read you started posting videos on YouTube in 2006. How long before you felt, “This is it. This is going to be something big.”

Alex: Right from my first thirty subscribers, I began talking to the audience that was there and making videos directly for them and replying to comments, but I never saw it as a “fan base”—I mainly just figured we were all bored kids. My first experience of being treated like a celebrity of sorts was not until four years later in 2010, when I did a few gigs with a band I was in at the time (comprised of YouTubers) and would go to really small parts of the UK like Norwich and there’d be two hundred people there all screaming for us and going crazy.

Me: Ultimately, you need money though, to be an artist. You can’t be a starving artist forever. When you don’t go with a big label you have three choices: YouTube ads, iTunes downloads, and performing. Which of these avenues worked for you?

Alex: Performing wasn’t an avenue for me—the only gigs I’ve done are one-off launch events (to launch my album for example) or gigs with friends (as I mentioned). I really don’t feel the need to gig when I can reach my audience online and hit everyone at once, all over the world, and not exclude anybody, which a tour doesn’t do.

Lesson Number Two: All the conventional methods for making money and distribution are out the window

because the barriers to entry that create the premium value are gone.

Alex: Of the other two—I released my first musical thing (a compilation of YouTube covers called YouTube Tour) in 2007, I think it was, and it made a couple hundred bucks. Then in 2008 they introduced the YouTube partnership program and I was one of the first partners. Back then I made maybe $300 a month. Then it slowly rose, and at the same time my first album came out in October 2009, so with the money from that plus YouTube I moved out in March 2010 to a place with my best friend and we paid £600 each on rent so it wasn’t too bad. It used to be about equal what I made from YouTube and what I made from music, but since “Forever Yours” got to #4 in 2011, my music sales have been way more than my YouTube. Typically I make around £3500 a month from YouTube (I’m on a network so they can sell the ad space higher) and at least £10,000 a month from music and merch sales. I’ve also done other projects—I co-created a card game with my cousin, which we sell online. I have a business called Lifescouts that I launched this year—which add a bit of extra cash to the pot also.

Me: Isn’t this a little like what Ani DiFranco did? She never signed with a major label. She just did her own thing.

Alex: I think the main difference was she was constantly touring and I never have. Also she got her independence by forming her own label. I don’t have a label at all.

Me: Have the labels ever reached out to you?

Alex: Labels have never known what the hell to do with me. I always went in with an open mind—I don’t like the idea that being proudly unsigned/independent instantly means I’m white and they’re black and we have to duel to the death or whatever. There are a lot of things I do on my own because I have to, so I’ve got good at them, but it would definitely be easier with outside help! So I was willing to hear what they could offer and how we could work together and I still would be, but I don’t think labels are ready to be that humble. They want to control everything. I like being able to decide my own songs and film my own music videos. I’ve had several meetings with Island Records in the UK, the last of which ended with the guy saying he doesn’t think I’m ready to be on a label yet because “We only signs artists we can sell at least a million copies of in the next three months”—but if he’s waiting for me to get to that point without him, why do I need the label ever? I’ve also met with Warner, Sony, EMI—they were all the same. None of them expected to justify themselves, and at best they were just trying to “figure out my secret,” and at worst they were completely uninformed and lazy (

see my video on the subject

, which sums it up better than I ever could here.).

Me: But what would you use the labels for now?

Alex: I guess it would be great to get their help. I’ll give you an example. I write my music, play my music, make my videos, design the albums, and so on, but it does provide some validation to be in physical stores.

So a ten-year-old kid who liked my stuff told his dad he should work with me. The dad was with distribution with Universal. So I did a one-off distribution deal with Universal where I did everything but they got me in every HMV. It was great. Nobody said I could sell physical CD singles but I sold ten thousand in the UK.

Lesson Number Three: Everyone will say you CAN’T.

Especially when you’re young, but if you pick and choose how to work with the entrenched system, you CAN.

Lesson Number Four: The power of the community you build

will be felt in ways you can’t predict (a ten-year-old fan, for instance).

Me: You clearly have a long-run view of what artists should be doing and where the industry is going. Where do you think the music industry will be in ten years?

Alex: I don’t think it matters where I see the music industry in ten years—I look at where the music industry is now and it’s not helping me, so I’ve learned to exist without it! What I’d like in ten years is for the music industry to be in a place where it supports me more, but that’s a long time to hope for that. The thing with the long-run view is that it’s actually a series of short spurts. It’s more like the general public are on the second floor of a building and every single/music video I release affords me a bounce on a trampoline outside. So for a second I’m up to the window saying, “Heyguyslookatme,” and then if they don’t see me I just fall down again and make a new song and try again. If one of my tracks catches fire, it’ll all happen very quickly, but when it doesn’t you just have to try again.

Lesson Number Five: Persistence is more important than industry validation

because it’s not the industry that is buying what you’re selling.

Lesson Number Six: Focus on what you can do for your art/business right now

instead of trying to aim for things ten years for now.

Me: What should most artists/creators do to keep going when things look their most frustrating? Most people give up. And, frankly, most people are no good. How did you keep going from 2006 to now, even when things looked bleak?

Alex: To help with knowing if you’re good or not,

you need a mentor. (Lesson Number Seven)

You have to have someone who either knows the industry or knows what’s commercial or successfully experimental or whatever it is you’re trying to achieve with your music and can tell you honestly whether or not you’re meeting that standard. I have a now-very close friend who used to work in the industry a lot, broke songs like “Who Let the Dogs Out” and “I Get Knocked Down But I Get Up Again”—we met through a mutual friend and I would just send him songs and he would say “not a hit, not a hit, not a hit” until eventually I sent him “Forever Yours” and he said “You’ve done it! Now break it.”

He didn’t help me, he just advised, but you need someone like that who you trust. The other thing with giving up is that I simply can’t. Sometimes I have low points and I spend a month or two not working on music at all, but then someone will play me an amazing new song, or I’ll watch one of my music videos back, or watch the Grammy’s and I think “I have to be doing this.” I can’t give up because I want it too much, and however hard it might be, it’ll be worse if I wasn’t pursuing what I love.

Lesson Number Five (redux): Persistence, there it is again.

Me: How did you get into all of this? How did you build the so-called ten thousand hours to be an expert?

Alex: I grew up with my mum listening to the radio whenever we were around the house, driving to and from school, etc. Music’s always been a huge part of my life. And there’s so much more to learning about good songwriting than the actual writing, in the same way writers tell you to read a lot if you want to be a good writer. My favorite part about developing as an artist is spending hours listening to music, listening to every Michael Jackson song and looking for commonalities, patterns, the way the production sounds, how the style varies. I’ve been known to draw out graphs that plot the melody of a chorus so then I can see visually how a song moves and how it varies from track to track. I started writing songs when I was thirteen. I started writing not-bad songs when I was seventeen. I wrote “Forever Yours” when I was twenty-two and the rest of the songs on my new collection last year at age twenty-three so I’ve been doing it ten years now and I know I still have a lot to learn. In a way that’s the most exciting thing—to hear the difference in the songs I’m making between this year and the last, and then think “What will I be making by NEXT year?”—there’s always room to grow and that’s exciting.

Me: How do you engage your fans outside of your music? How do you “build the tribe,” in Seth Godin speak?

Alex: It’s just YouTube. I have Twitter and Facebook only because I sort of feel I have to, because I need to reach people in those places. That’s not to say I’m just on auto-pilot on those places, but I’d much rather not have to use those services. Part of why it’s necessary right now is that I don’t have enough reach in the “real world” for me to allow other people to promote what I’m doing on my behalf, but my Twitter and Facebook are effectively work accounts that just update people on what I’m up to. For the personal connection, it’s all YouTube. I love it there. It’s such a creative outlet, I’ve been making videos for seven years and never got bored of it, one or two videos a week regularly all that time.