Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (109 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

The result was a meeting of the

Sejm

(Diet or Assembly) in Warsaw in 1573, at which a clause on religious freedom was unanimously approved in the agreement ('Confederation') proposed with the new king. It was couched as a declaration of the nobility's intent, which Henri would have to recognize to gain his throne:

Since there is in our Commonwealth (

Respublica)

no little disagreement on the subject of religion, in order to prevent any such hurtful strife from beginning among our people on this account as we plainly see in other realms, we mutually promise for ourselves and our successors forever . . . that we who differ with regard to religion will keep the peace with one another, and will not for a different faith or a change of churches shed blood nor punish one another by confiscation of property, infamy, imprisonment or banishment, and will not in any way assist any magistrate or officer in such an act.

65

The young King Henri agreed, despite misgivings from his French advisers and furious protests from the Polish bishops (only one of whom signed the Confederation). While the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth endured, the Confederation remained a cornerstone of its political and religious life. The agreement of 1573 gave credibility to the proud Polish claim (almost but not quite true) to be a land without execution of heretics: a 'State without Stakes'.

66

Europe entered the seventeenth century with the constitutionally governed realms on its eastern flank, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, showing other Europeans how they might make the best of the schisms in Western Christianity. Subsequent history of the region sadly betrayed that early promise and held back the achievement of a wider toleration. New initiatives had to appear elsewhere, and they only came in the wake of vicious religious warfare which blighted much of Europe and its British archipelago into the eighteenth century.

REFORMATION CRISES: THE THIRTY YEARS WAR AND BRITAIN

A remaining problem of the Reformation was the boundary between its Protestant and Catholic halves of western and central Europe, since Catholic Habsburg power straddled north and south. Charles V had not been able to sustain his early success in the Schmalkaldic Wars, and the Peace of Augsburg between the Habsburgs and Protestants in 1555 established for the first time a reluctant recognition by a Catholic monarch of a legal existence for Protestants. From then on, within the patchwork of jurisdictions which the Holy Roman Empire had become, each ruler could decide on which side of the Reformation divide his territory and subjects were to fall: the principle of

cuius regio, eius religio

. The arbitrariness of this solution was mitigated by the extreme complication of imperial territorial boundaries, which meant that subjects who disagreed with their ruler might only have to relocate by a mile or two, but there was also a major limitation.

The 1555 settlement reflected the realities of the Schmalkaldic Wars: the bulk of Protestants fighting the Catholics had been Lutherans, and the only two permissible religions of the empire were papal Catholicism and Lutheranism. Only four years after Augsburg came a twist of genealogical fate which brought the accession of a serious-minded new monarch in the Palatinate who adhered to neither of these confessions. As the Elector Palatine Friedrich III, he championed a non-Lutheran and increasingly confessionally Reformed Church in the Palatinate (that Church which created the Heidelberg Catechism of 1563: see p. 637). Although Friedrich's successors wavered between Lutheranism and the Reformed, other German princes followed his example in turning away from increasingly dogmatic Lutheranism towards the creation of Reformed Church polities, reorganized from Lutheran Churches in a 'Second Reformation'.

To their sorrow and puzzlement, these rulers found that their Lutheran subjects were not pleased. When in 1614 the unfortunate Elector Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg tried to defend his Reformed preachers against popular hatred, a cry was heard in the Berlin crowd: 'You damn black Calvinist, you have stolen our pictures and destroyed our crucifixes; now we will get even with you and your Calvinist priests!'

67

The Reformed were confronting Lutheran Churches which, amid an enormous diversity of traditional practice, seemed to have become the shelter for traditional religion as it had been before the Reformation upheavals. The Lutheran Mass (still so called) continued to be conducted partly in Latin, by clergy in vestments, who even elevated the consecrated bread in the service in traditional style. Luther in popular memory had become a saint, his picture capable of saving houses from burning down, if it was fixed to the parlour wall. Right into the nineteenth century, Danish Lutheran visitation teams were alarmed to find rural parishes where the faithful delighted in pilgrimages, holy wells, festivals and intercession to saints from centuries before, and Denmark was not unique around the Baltic.

68

By the end of the sixteenth century the Reformed grouping in central Europe could not be ignored, but still they had no place in the 1555 Augsburg agreement, which strictly recognized only those who adhered to the Augsburg Confession. The situation was not made any easier by the fact that there was no agreement as to whether this meant solely the original 'unvaried' Augsburg version of 1530, or included a

Variata

revision which Melanchthon had undertaken in 1540, hoping (to Luther's distinct annoyance) to accommodate the theology of those who did not take the Lutheran line on the Eucharist.

This instability was the background to the eventual outbreak of continent-wide war, and the flashpoint was the kingdom of Bohemia, which for a century had been ruled by the Habsburg dynasty. The Bohemians had stonily preserved their established Hussite or 'Utraquist' Church, product of their fifteenth-century risings against the Holy Roman Emperors (see pp. 571-4), against any Habsburg or Catholic encroachment. In 1618, provoked by increasing Habsburg self-assertion, they began their defiance of the dynasty by imitating their ancestors in a second 'Defenestration' of imperial representatives in Prague (see p. 572), although this time a providentially placed heap of straw broke the victims' fall. They then looked around Europe for a champion to defend their independence and their Utraquist inheritance: since Utraquism was an exclusively Bohemian movement, a monarch to supplant the Habsburgs would have to be recruited from among the Protestants of the sixteenth-century Reformation. In 1619 the Bohemian nobility elected as the next king of Bohemia, in preference to the Catholic Habsburg claimant, the Elector Palatine, Friedrich V. He was an idealistic and charismatic ruler, firmly Reformed in his confessional allegiance, and he had already generated febrile excitement across the continent as a possible leader for all Europe against the popish menace. As the Bohemian electors were choosing Friedrich, the militantly Calvinist Prince Gabor Bethlen of Transylvania made his own bid to attack God's enemies (and acquire the Hungarian throne) by routing Habsburg armies in Hungary and taking over the Habsburgs' territories there. The Ottoman sultan joined in the fray by offering his support to the Transylvanians.

The Habsburgs reacted quickly to this hammer-blow to their power, and their reconquest of Bohemia proved unexpectedly easy. Friedrich's Reformed faith put him quickly at odds with his Bohemian sponsors; the conservative Utraquists were outraged by the iconoclasm which his Reformed preachers encouraged in Prague, and a rout by Habsburg forces at the Battle of White Mountain in 1620 sealed Friedrich's fate. Immediately the Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand began dismantling a century of safeguards for Protestantism and two centuries of established status for the Utraquist Church, which is the only Church since the disappearance of the Arians totally to have vanished from European Christianity. Sustained attacks on Protestant privileges followed in Austria as well; it was the beginning of a successful effort to install the most flamboyant variety of Counter-Reformation Catholicism as an almost monopoly religion in the Habsburg heartlands, a remarkable achievement considering that in 1619 around 90 per cent of the population of Bohemia were not Catholic.

While Friedrich fled from his briefly held second throne into lifelong exile, European powers both Protestant and Catholic were deeply worried by the Habsburg triumph. Not only Protestants were alarmed at the intransigent terms of Ferdinand's Edict of Restitution in 1629, which restored lands to the old Church lost even before the Peace of Augsburg, and virtually outlawed Reformed Christianity in the empire: the alarm was enough to provoke many more to take up arms. Catholic France and Lutheran Sweden both intervened in wars which proved so destructive and prolonged that it was only in 1648 that the exhausted powers were able to agree on the Treaty of Westphalia to end the Thirty Years War. The boundaries between Catholic and Protestant territory chosen represented some rough parity of misfortune in terms of the territories which Catholics and Protestants had held at the stage that warfare had reached in the year 1624. Those religious boundaries still survive in European society at the present day.

At the end of it all, Western Christianity would have to face new realities. On the outbreak of war, many believed strongly in the sacred reality and God-given destiny of the Holy Roman Empire: these were principles which for a serious-minded prince like the Lutheran Elector Johann Georg of Saxony even now outweighed his suspicion of the Catholic Emperor Ferdinand, and made him support the Emperor against fellow Protestants during the war. After 1648, there was no prospect that this foundational institution of medieval Western Christendom would ever become a coherent, bureaucratic and centralized state, not even on the open model of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (itself now in deep crisis: see pp. 536-9). Imperial institutions continued to operate, and provided a framework for German life, but Christian rulers would have to devise other ways of understanding how and why they ruled. Having seen the results of religious war through the years of the Reformation up to 1648, fewer of these rulers would be inclined to embark on crusades for the faith, especially against fellow Christians. Crusades simply had not worked.

Alongside this struggle in mainland Europe was a conflict which took place over more than twenty years from 1638 in the Atlantic Isles, the three British kingdoms of Ireland, Scotland and England ruled over by the Stuart dynasty. Once more, the main issue was religion.

69

When dynastic quirks delivered Ireland and England into the impatient hands of James VI of Scotland in 1603 on the death of the unmarried Queen Elizabeth, he found himself presiding in his two new kingdoms over established Churches which were something of a puzzle. Were they part of the Reformed world? James was himself a devout Reformed Protestant who had done his best to cope with (and curb) a Reformed Church of Scotland convinced that it had the God-given right to tell him what to do. He had been inclined to disparage the Church of England, aiming to please his Scottish clergy, and perhaps at that stage genuinely disapproving of an institution which he had never personally experienced; in 1590 he sneered that the English communion service of Cranmer's

Book of Common Prayer

was 'an evil said masse in English, wanting nothing but the liftings' (that is, the Catholic and Lutheran elevation of the consecrated host). He may also, in another sneer from 1598, have invented the word Anglican'.

70

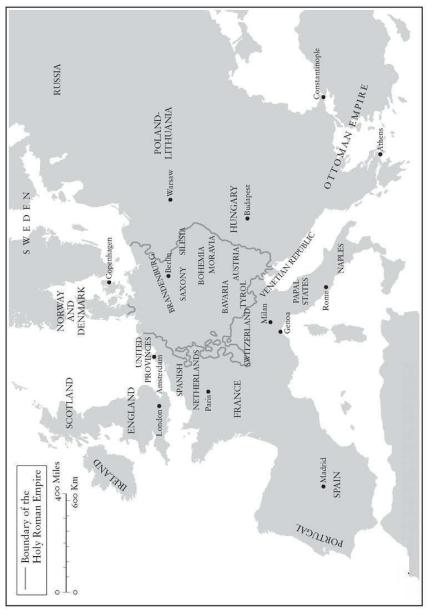

19. Europe after the Peace of Westphalia

Experience of the real thing changed his mind: as James I of England, he found himself enthusiastic for the Church of England. Its confessional statement, the Thirty-Nine Articles of 1563, placed it firmly in the Reformed camp in terms of doctrine, but its liturgy, devised mainly by Cranmer half a century before, was more elaborate than any other in the Reformed world. For reasons locked up in the mind of the late Queen Elizabeth, it had retained not only bishops (Scotland had bishops too, after a fashion), but fully functioning cathedrals, with a positively medieval apparatus of worship: deans, canons, paid choirs and organists, a large ancillary staff, and an inclination to use the English Prayer Book in a ceremonial style. The survival of cathedrals had given rise to an initially small group of English clergy and some lay sympathizers who had a very un-Reformed attitude to the Church, a style which in its later forms has come to be called 'High Church'.

These High Churchmen did not exactly despise preaching (indeed, one of their most influential members, Lancelot Andrewes, was a famous preacher), but they emphasized the solemn performance of public liturgy and the offering of beautiful music in settings of restrained beauty as the most fitting approaches to God in worship. They spoke much of the value of the sacraments: indeed, another useful label for them might be 'sacramentalist'. To emphasize the sacraments placed more importance on the special quality and role of the clergy who performed the sacraments, so sacramentalists were also more clerical in their outlook than was common among English Protestants. They mostly held little respect for the Reformed scheme of salvation which stressed predestination, and in allusion to followers of a Dutch academic, Jacobus Arminius, who were also challenging predestination in the Dutch Reformed Church, during the 1610s their enemies took to calling them 'Arminians'.

71

Some of them, first in private but then provocatively in public, began saying that many aspects of the Reformation were regrettable. That might suggest a more radical conclusion that much in the Reformation should be reversed.