Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (123 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

Slavery formed another problem for and a blot on English-speaking Christian mission. As the southern colonies and English islands in the Caribbean developed a plantation economy, particularly for tobacco and sugar (cotton came much later), they became deeply enmeshed in the system of importing African slaves which had already sustained the Iberian colonies for more than a century. The first record of enslaved people in Virginia is as early as 1619.

21

It was ironic that in the 1640s and 1650s, as the English on both sides of the Atlantic were talking in unprecedented ways about their own freedom and rights to choose, especially in religion, slaves were being shipped into the English colonies in hundreds, then thousands. Christianity did not seem to alter this for Protestants any more than it had for Catholics. An act of the Virginia Assembly in 1667 spelled out that 'the conferring of baptisme doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or Freedome', which was only to restate the policy already adopted by the Portuguese in their slave trade, and to look back to the position of English serfs, formally enshrined in English common law (as it still is).

22

It was a different position from that of the Reformed Protestant Dutch in their seventeenth-century colonial venture in the southern Cape of Africa - there, slaves who were baptized could not be sold again, and the Dutch were therefore careful to keep those baptized to a minimum.

23

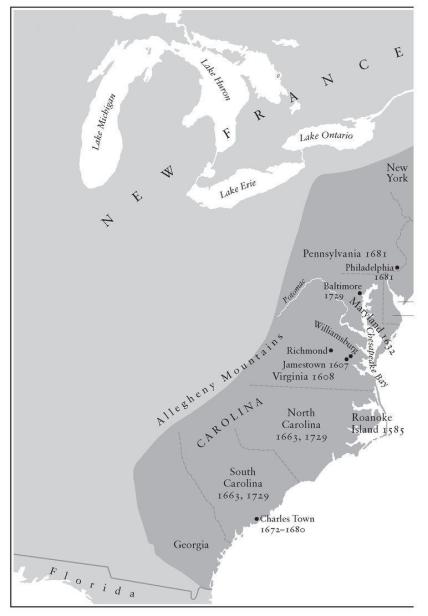

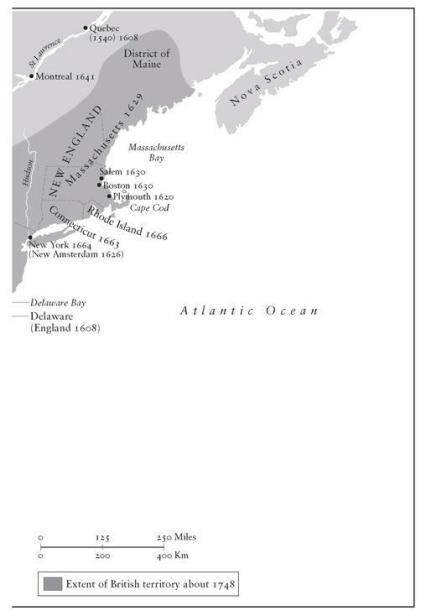

21. North America in 1700

The double standard seemed to be ever more entrenched. The great exponent of toleration and liberty John Locke, in his

Two Treatises of Government

, resoundingly declared to Englishmen that 'Slavery is so vile and miserable an Estate of Man . . . that 'tis hardly to be conceived, that an Englishman, much less a Gentleman, should plead for 't'. But that is precisely what Locke himself had done when (as one of the first hereditary peers created in English North America) he helped first to draft and then to revise a constitution for a vast new English colony in the south called Carolina, at much the same time in the 1680s as he was writing

Two Treatises

. Blacks were different.

24

Slave numbers rocketed at the end of the seventeenth century: blacks outnumbered whites in South Carolina by the 1710s, and in Virginia the proportion of blacks to whites shot up from less than 10 per cent in 1680 to about a third in 1740. This is the context for the remarkable liturgical innovation of one South Carolina Anglican clergyman, Francis Le Jau, who added to the baptism service a requirement that slaves being baptized should repeat an oath 'that you do not ask for the holy baptism out of any design to free yourself from the Duty and Obedience you owe to your Master while you live'. This reflected a clerical dilemma in a Church so dominated by the laity: when masters were putting up much resistance to converting slaves, was it better to let souls perish or to accept the norms of the society in which the Church found itself?

25

As early as the mid-seventeenth century, Virginia in the south and New England in the north had created two contrasting forms of English-speaking colony. Both were firmly committed to their different patterns of established Churches, just as in Europe, though Rhode Island remained as a thorn in the side of the New England establishments and was a model for their gradual loosening of official restrictions on other Protestant congregations. Between the two regions, a variety of 'Middle Colonies' was set up, not all initially English. Swedish Lutherans settled on the Delaware River, and the Protestant Dutch seized a spectacular natural harbour in the Hudson estuary which they named New Nether-land and which quickly emerged as the focus for European shipping along the North American coast. An English flotilla annexed this tempting prize during the Anglo-Dutch Wars in 1664, and its capital New Amsterdam on the Manhattan peninsula became New York, only briefly retaken by the Dutch in 1673.

Once more the aim of the Swedes and Dutch had been to reproduce the national Churches back home, but even before 1664 the religious cosmopolitanism of the northern Netherlands had already been reproduced in New Amsterdam, whether the Dutch Reformed Church liked it or not. That included pragmatic Dutch toleration of a wealthy Jewish community, since there were a significant number of Jewish shareholders in the Dutch West India Company, the colony's proprietor. English rule was the coup de grace to any thoughts of a Dutch Reformed monopoly. It was New York that first experienced the bewildering diversity of settlers which, during the eighteenth century, swelled into a flood, and made any effort to reproduce old Europe's compartmentalized and discrete confessional Churches seem ludicrous. Rather than the colonies of north and south which had been English from the beginning, this Dutch settlement pointed to the future diverse religious pattern of North America.

26

Further religious experiments intersected with the crises of mid-seventeenth-century England in different ways from New England and Virginia. In 1632 Roman Catholic aristocrats friendly with Charles I sponsored a colony in a region known as the Chesapeake north of Virginia, and named it Maryland after the King's Catholic wife, Henrietta Maria. In fact the Royalists' defeat in the English civil wars meant that Catholics did not take the leading role in Maryland. Feeling that their already tenuous position was under threat, in 1649 they seized on a brief moment of local strength and sought to create a unique freedom to practise their religion by outmanoeuvring their Protestant opponents in a huge concession. They guaranteed complete toleration for all those who believed in Jesus Christ. They ordered fines and whipping for anyone using the normal religious insults of seventeenth-century England, elaborately specified in a list: 'heretic, schismatic, idolator, Puritan, Independent, Presbyterian, Popish priest, Jesuit, Jesuited Papist, Lutheran, Calvinist, Anabaptist, Brownist, Antinomian, Barrowist, Roundhead, Separatist'.

27

This was an extraordinary effort to blot out the bitterness of the Reformation; it approached Rhode Island's universal toleration by a very different route. Maryland showed the limitations of its vision by still ordering property confiscation and execution for anyone denying the Trinity, and Anglicans seized control of the colony in the 1690s, doing their best to restrict Roman Catholic rights - an ironical outcome of the 'Glorious Revolution', which is seen in English history as a milestone in the development of public religious toleration (see pp. 733-6). Nevertheless, amid the steadily encroaching diversity of the whole colonial seaboard, the Maryland example was not forgotten.

A new chance for the hard-pressed Quakers came when one of their number, William Penn, became interested in founding a refuge for them. He was the son of an English admiral, and friendly with the Catholic and nautically minded heir to the throne, the future James II. Drawing on these useful connections, he got a royal charter in 1682 for a colony to be called Pennsylvania, in territories lying between Maryland and New England. His plan was bold and imaginative: going further than the Catholic elite of Maryland, he renounced the use of coercion in religion, and granted free exercise of religion and political participation to all monotheists of whatever views taking shelter in his colony. He also tried to maintain friendly relations with Native Americans. Soon Pennsylvania came to have a rich mix not simply of English Protestants, but also Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, Lutherans and the descendants of radical Reformation groups of mainland Europe who were fleeing from Roman Catholic intolerance in central Europe (see p. 647). Among the latter, the Old Order Amish from Switzerland have done their best ever since to freeze their communal way of life as it was when they first arrived in the early eighteenth century.

28

All this diversity proved destructive for Penn's original vision of a community run according to the ideals of the Friends. Under pressure from the English government, Pennsylvania's assembly even disenfranchised Catholics, Jews and non-believers in 1705.

29

Soon good relations with the native population were also badly compromised. Pennsylvania nevertheless fostered a consistent hatred of slavery among Friends, a development of great future significance for all Christians (see p. 869). It set another notable example: no one religious group could automatically claim exclusive status, unlike nearly all other colonies where a particular Church continued to claim official advantages even if it was a minority. This was the first colony to evolve the characteristic pattern of religion of the modern United States of America: a pattern of religious denominations, none claiming the exclusive status of Church, but making up slices in a Protestant 'cake' which together adds up to a Church. Anglicanism did manage to strengthen its position in the southern English American colonies after Charles II's restoration (even in cosmopolitan New York), gaining established status in six out of the eventual thirteen. However, the origins of so many colonies in religious protest against the Church of England back home guaranteed that Anglicanism would never fully replicate its full English privileges in North America.

Established churches might have been able to resist the growing pluralism better if they had more effectively set up their structures of government, but virtually everywhere except Massachusetts, the colonies suffered a shortage of clergy in the first formative century, and lay leaders of local religion were generally less inclined to take an exclusive view of what true religion might be than professionally trained clerics. In this they were aided by a strong consideration swaying many promoters of colonies: religious coercion discouraged settlement and was therefore economically bad for struggling colonial ventures. Reformation Europe had known religious toleration; now religious liberty was developing. Toleration is a grudging concession granted by one body from a position of strength; liberty provides a situation in which all religious groups compete on an equal basis. We have already seen precedents: first in the 1520s the pragmatism of the Graubunden in Switzerland, then the Hungarians and Transylvanians in the Declaration of Torda, soon followed by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's Confederation of Warsaw (see pp. 639-43). Just as the increasing confessional rigidity of old Europe was turning from these sixteenth-century ideals, a new European enterprise was taking up the challenge.

THE FIGHT FOR PROTESTANT SURVIVAL (1660-1800)

The growing success and stability of these new transatlantic Protestant polities (gained at the price for Native American societies of increasing disruption and exile westwards) contrasted with a long-drawn-out crisis for Protestants in late-seventeenth-century Europe. The Habsburgs began systematically dismantling a century and more of Protestant life in central Europe from Bohemia to Hungary, Catholic advance in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth continued apace, and France re-emerged under Louis XIV (reigned 1643-1715) as a major European power with an aggressively Catholic agenda. The Stuart dynasty restored in Britain in 1660 was from its return a client of Louis, seeking his financial support against its stridently but selectively loyal and inconveniently Anglican English Parliaments. Charles II and James II became pawns in Louis's plans, which included improving, or better still reversing, the marginal position of Catholics in the Atlantic Isles.

30

Louis XIV died an exhausted and defeated old man, but in his prime he directed an army of 400,000, supported by a taxable population of twenty million; he had increased the size of that army fivefold in four decades.

31

Beyond his own borders, he spurred on the Duke of Savoy in murderous campaigns against Savoy's Protestant minority, and in 1685 he overturned his grandfather Henri IV's religious settlement for France by revoking the Edict of Nantes - 150,000 Protestants are estimated to have fled France as a result, the largest displacement of Christians in early modern Europe.

32

Louis conquered largely Protestant lands of the Holy Roman Empire in Alsace, making a Catholic Strasbourg out of Lutheran Strassburg, which long before in Martin Bucer's time had been the prime candidate to lead the Protestant world (see pp. 629-30). In his military campaigns of 1672, Louis nearly succeeded where the Spanish monarchy had failed, in overwhelming the United Provinces of the Netherlands - and in that ambitious venture lay the seeds of his own failure. For the outrage of France's invasion provoked Prince Willem of Orange, appointed Stadhouder (the word which in French would be 'Lieutenant') by most provinces in the Netherlands, to take up arms against the Catholic Leviathan. His ancestor Willem 'the Silent', eventually murdered by a Catholic fanatic, had done the same a century before, but Prince Willem would more than avenge his fate.