Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (15 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

Nevertheless it is worth listening for the voice of Jesus, particularly in the three Gospels which develop common material and edit it in their own ways. Of the three, Mark's text is generally held to be the earliest, with separate forms of development and use of additional material in Matthew and Luke. They are all likely to have been written in the last three decades of the first century, around half a century after Jesus died, but certainly no later than that, since they are already beginning to be quoted in other Christian texts datable not much later than 200 CE. They seem to have been based on earlier collections of sayings of Jesus; they represent selections by different Christian communities anxious to put boundaries on the stories of good news about Jesus's life and resurrection, and also to bring their own perspectives to the good news. The three Gospels are together known as the 'Synoptic' Gospels to distinguish them from the Gospel of John, which was probably written a decade or two later than they were; the three present the basic story of Jesus in a similar way, quite differently from John's narrative - so they 'see together', the root meaning of the Greek

synopsis

.

19

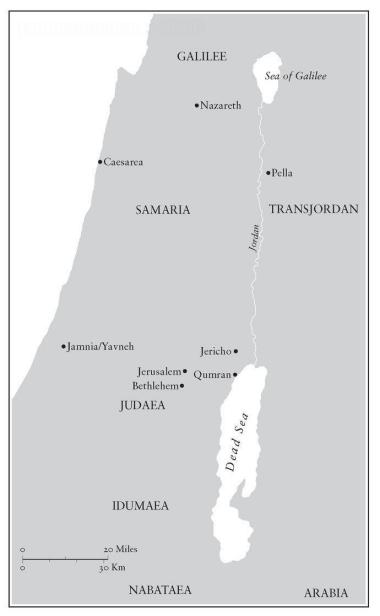

3. Palestine in the time of Jesus

To a surprising degree, the Synoptic Gospels reveal distinctive quirks of speech in Jesus's sayings which suggest an individual voice. One very common and very Semitic peculiarity, for instance, is found more than a hundred times in these three Gospels: Jesus has a trick of setting one proposition against an opposed proposition. So Mark has Jesus saying, 'With men it is impossible, but not with God; for all things are possible with God.' The likelihood that this was how Jesus spoke is strengthened by the fact that Luke seems to dislike the literary form, perhaps finding it inelegant, and from time to time he weakens Mark's original formulation - in this case down to 'What is impossible with men is possible with God.'

20

The form has its precedents in the Hebrew literature which Jesus would have known, but it is noticeable that those previous examples tend to have a stress on the first element, while Jesus mostly stresses the second. This suggests an urgency to his message, a punchiness which would make each saying easy to remember and recite long after listeners had first heard it shouted in public.

21

Another quirk is Jesus's frequent and apparently unprecedented use of the emphatic Hebrew and Aramaic exclamation 'Amen!' before he makes a solemn pronouncement: 'Amen I say to you . . .' The word was considered so important that it was preserved in its original form in the Greek biblical text; in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century versions of the English Bible, it becomes 'verily'. John's Gospel develops the peculiarity even further than the Synoptics by customarily doubling it - 'Amen Amen I say to you . . .', which is probably gilding the lily in the interests of John's exalted view of Jesus Christ as cosmic Saviour.

22

The effect is rather like Dr Samuel Johnson's famous characteristic phrase 'Depend upon it, Sir . . .' as he launched on some particularly final or crushing remark: it is intended to emphasize the uniquely personal authority of the speaker, and it may be contrasted significantly with the reported-speech construction of a phrase which had been much used in the Tanakh, 'Thus says the Lord'. Jesus in the Gospels is his own authority. He is, after all, the one who has seized the intimate word

abba

and used it when speaking to God.

Along with this sense that Jesus has a prerogative to speak with greater power than that of the ancient prophets, one hears irony, indirectness in his voice, particularly in a mysterious phrase of his which continues to provoke debate among biblical scholars, 'the Son of Man'. Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels virtually never calls himself 'Son of God', though he does in John (see p. 103). He repeatedly uses this other phrase: for instance, 'The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath: so the Son of Man is Lord even of the sabbath.'

23

All four Gospels record the usage frequently, though there is no overlap at all between the Synoptic Gospels' sayings of Jesus which include it and the sayings in John's Gospel. This may suggest that John created 'sayings of Jesus' for his own purposes. In the extensive surviving writings of the Apostle Paul about Jesus, the phrase never occurs - nor does it recur beyond scriptural texts over the next few centuries in the works of Christian writers, for whom it would have been less than helpful as they debated how Jesus Christ could be both human and divine. Those silences make 'the Son of Man' all the more striking as it rings through the Gospels, virtually exclusively in the reported words of Jesus.

24

It echoes a use of a phrase, 'One like a son of man', in the Book of Daniel, a work about two centuries older than Jesus's time, where the reference is to one who takes up an everlasting reign to replace the demonic kingdoms of the physical world.

25

Therefore it points to a Jesus who saw himself and proclaimed himself as the Messiah whom Jews expected - but in a curious, oblique way. There is no positive evidence that anyone in the age of Jesus would have recognized 'Son of Man' as a special title - in fact there is not much evidence in the Gospels that Jesus used any particular title for himself, whatever others called him. Rather 'Son of Man' may reflect in Greek a phrase in Aramaic (Jesus's everyday language) meaning 'someone like me', sometimes with the sense that this meaning extends to the group who have the privilege of listening to what Jesus is saying - 'people like us'.

26

It is always difficult to catch irony and humour across a gap of centuries; but if evanescent tints remain in the phrase 'Son of Man', they are much clearer in another distinctive and engaging feature of Jesus's discourses, the miniature stories or 'parables' which illuminate aspects of his message. There is nothing like the parables in the writings of Jewish spiritual teachers (rabbis) before Jesus used them; interestingly, they emerge as a literary form in later Judaism only after Jesus's death. Was this form of Jesus's teaching so successful that it impressed and influenced even Jews who did not become his followers?

27

Because the parables are stories, they have woven themselves into general memory more than any other aspects of Jesus's message: the Good Samaritan; the Wise and the Foolish Virgins; the bad and good use of talents - a word which has itself been enriched thanks to the parable of the Talents, whose original reference was simply to coins called talents and not to gifts of personality. They resonate with the sense of a single voice, not least because of all the odd, counter-intuitive things which happen in them.

Nevertheless, many of Jesus's parables would have had all the more impact because they drew on existing stories which ordinary people knew: for instance, the contemporary Alexandrian Jewish tale of a rich man's funeral and a poor man's funeral and the reversal of their fortunes in the next world, which lies behind the different narrative thrusts of two well-known parables, the Great Man's Rejected Supper and the parable of Dives ('Rich Man' in Latin) and Lazarus the beggar.

28

Originally these pointed little stories were directed to a particular audience and situation: so Mark and then Matthew and Luke developing Mark's text record one parable about wicked tenants who murder the son of their landlord, and they specifically say that it was told 'against' and in the presence of the leaders of the Temple in Jerusalem, provoking their fury.

29

In some cases, such as the story of the great man who stages a banquet which is then rejected by the guests, it looks as if the Gospel writers took a parable story from one specific original context and gave it a new one, even expanding and complicating the story to get a new meaning across which would be helpful to later generations in the emerging Church.

30

The overwhelming preoccupation in the parables, despite their various accretions after Jesus's time, is a message about a coming kingdom which will overwhelm all the normal expectations of Israel and take its establishment figures by surprise. People must be watchful for this final event, which is inevitably going to catch them unawares: so both the wise and the foolish virgins snatch a nap before the bridegroom arrives, but the wise virgins have provided ample oil for their lamps of celebration, still burning when they need to wake up.

31

In a gem of sarcasm, Jesus points out that a householder would not have left his house to be broken into if he had been informed of the burglar's intended hour of arrival - 'for the Son of man is coming at an unexpected hour'. How extraordinary to compare the fulfilling of God's purposes to an act of criminality, even violence!

32

Much celebration and joy run through these stories, which tell of feasts and wedding banquets, yet also custom, common sense and even natural justice are at times ruthlessly ignored: labourers in a vineyard who have done a full day's work are told to stop complaining when they get the same wage as latecomers who only put in an hour.

33

The coming kingdom will make up its own rules. The later Church found this an uncomfortable message as it settled down to make sense of people's everyday lives.

This sense that all the rules have changed is to be found in many of the sayings attributed to Jesus, particularly those which in Matthew's and Luke's Gospels have been gathered into an anthology, known from Matthew's version of it as the Sermon on the Mount (Luke's shorter version actually places the event on a plain, not a mountain, but somehow that setting has never captured Christians' imagination to the same extent).

34

It begins with a dramatic collection of blessings on those whom the world would call unfortunate, such as the poor, the hungry, those weeping, those who are widely hated. All these will have their fortunes precisely reversed. These 'Beatitudes' have remained as a subversive tug at the sleeve for churchmen in the centuries during which they have had too much worldly comfort, an encouragement for the oppressed, and even a stimulus to many Christians to seek out deprivation and practise humility - an inspiration to monks and friars in later centuries, as we will see. Jesus's breaking of conventions continues after the Beatitudes: traditional sayings are quoted, such as the admirable 'You shall not kill; and whoever kills shall be liable to judgement', and then they are put on the rack or disconcertingly extended to their logical conclusion. So physical killing ought indeed to be condemned, but so should all people angry with their brother who then turn the anger into verbal violence; they shall be liable to the Hell of fire.

35

There is much punishing fire flickering round the preacher's words. There is nothing gentle, meek or mild about the driving force behind these stabbing inversions of normal expectations. They form a code of life which is a chorus of love directed to the loveless or unlovable, of painful honesty expressing itself with embarrassing directness, of joyful rejection of any counsel suggesting careful self-regard or prudence. That, apparently, is what the Kingdom of God is like.

Jesus's preoccupation with the imminent kingdom is clear not only in all this material, and in his reference to Daniel's 'Son of Man', but also in 'The Lord's Prayer' which he taught his followers and which is embedded in different versions in both versions of the Sermon anthology.

36

The prayer moves straight from addressing the Father in Heaven to the plea 'Thy kingdom come'. It is also shown to belong to the earliest strata of the Gospel material even in its Greek form, because one of its petitions includes an adjective whose meaning has baffled Christians ever since: '

epiousios

', a very rare word indeed in Greek. The puzzling character of the word is not apparent in its common English translation, which suggests a very ordinary request, 'Give us this day our

daily

bread'. Yet

epiousios

does not mean 'daily', but something like 'of extra substance', or at a stretch 'for the morrow'. The first Roman Catholic attempt to translate 'The Lord's Prayer' into English from the Latin Vulgate in the late sixteenth century courageously recognized the problem, but also sidestepped it simply by borrowing a Latin word as 'supersubstantial'; not surprisingly, 'give us this day our super-substantial bread' never caught on as a popular phrase in prayer. If we can assign any meaning to

epiousios

, it may point to the new time of the coming kingdom: there must be a new provision when God's people are hungry in this new time - yet the provision for the morrow must come now, because the kingdom is about to arrive.

37

The evidence for Jesus's concentration on the imminence of the coming kingdom piles up, all the more strikingly because within decades of Jesus's death the Church began to have second thoughts on just how imminent it might be. The Apostle Paul hardly ever recorded what Jesus had actually taught, so it is all the more notable that he records as a 'word of the Lord' that 'the Lord himself will descend from Heaven with a cry of command, with the archangel's call, and with the sound of the trumpet of God' - phrases echoed (probably a few decades after Paul wrote) in Matthew's Gospel.

38

Jesus gathered around him twelve special disciples or 'Apostles' as the central figures in his public ministry: twelve was the number of the long-dispersed tribes of Israel, a sign that the fractured past and present were to be made perfect. Reportedly after Jesus's death, a new Apostle called Matthias was appointed out of two possible candidates to make up the Twelve, since Judas, one of the original Apostles, had betrayed Jesus to the authorities and then killed himself.

39

The fact that after that, most of the Twelve had little recorded impact on the early Christian story makes it all the more noticeable that the Jesus narratives in the Gospels still give such a prominent place to the selection of the Twelve and their role in his ministry.