Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (156 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

The death throes of the Ottoman Empire led to further disasters for Orthodoxy and the ancient Miaphysite and Dyophysite Churches of the East. Nineteenth-century massacres caused by the new self-consciousness of Ottoman Islam were outclassed by what now happened in Anatolia and the Caucasus. From the beginning of the war, the reformist 'Young Turk' regime in Constantinople saw the Christians of the region as fifth columnists for Russia (with some justification) and was determined to neutralize them. The measures it authorized were increasingly extreme, to the point that it is difficult to find historians outside Turkey who are not prepared to use the word genocide to describe the deaths of more than a million Armenian Christians between 1915 and 1916. One city, Van, largely Armenian in 1914, simply does not exist on the site that it then occupied.

16

Britain, Russia and France appealed to the Turks during the war to end these atrocities, threatening post-war retribution to those involved and denouncing these 'new crimes of Turkey against humanity and civilization'. The word 'humanity' had significantly replaced 'Christianity' in an earlier draft of the statement, and there was little comfort for Christian victims in the peace settlements which followed.

17

No official statement was made about the Armenian holocaust.

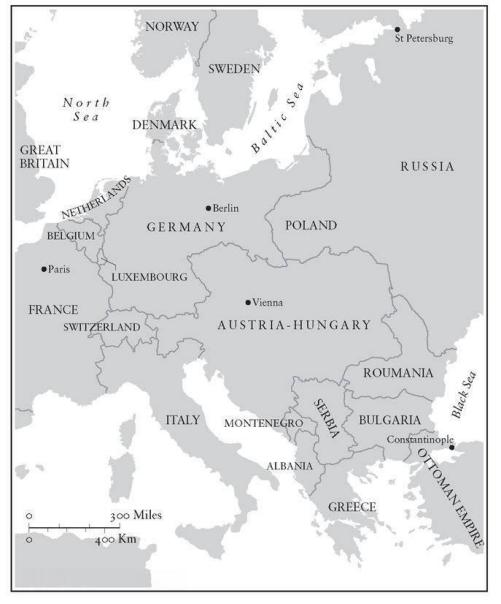

23. Europe in 1914

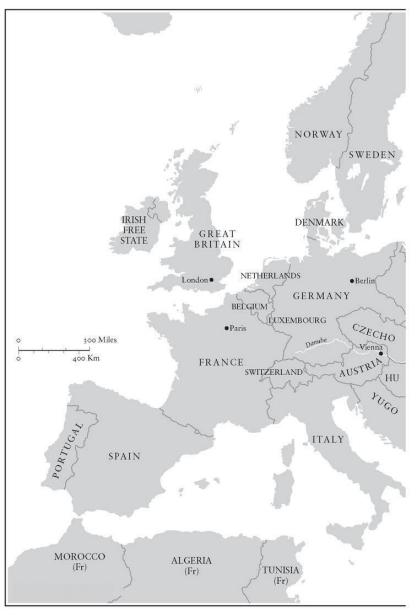

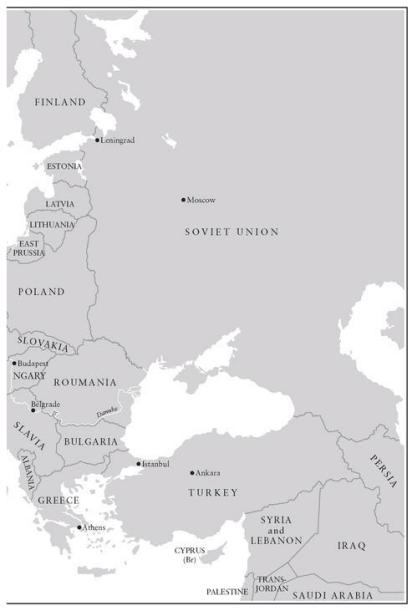

24. Europe in 1922

Besides this catastrophe was that of the Dyophysites in Mesopotamia and the mountains of eastern Turkey who, since the mid-nineteenth century, had exploited the findings of Western archaeology in the Middle East and rebranded themselves as 'Assyrian Christians'. While general war raged, they sought to carve out a national homeland to embody their new identity, in the face of massacres by Turks and Kurds. They were fortified by military victories against the Turks led by the brilliant Assyrian military leader Agha Petros, but after the war the British reneged on previous promises. Instead Assyrians found themselves part of a newly constructed multi-ethnic British puppet kingdom, Iraq, dominated by Muslims, where they fared increasingly badly at the hands of the Hashemite monarchy and its Republican successors. The two Gulf Wars at the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries brought them fresh miseries, especially the second, which has sent new streams of scapegoated refugees out of Iraqi territory.

18

The reason why the victorious Allies fell silent on the Armenians and betrayed the Assyrians had to do with a sudden post-war series of victories by Turkey. These brought further disaster for Eastern Christianity, in this case Greek Orthodoxy. With the Ottoman Empire prostrate, Greek armies occupied much of western Anatolia (Asia Minor), continuing various Balkan land-grabs from the Ottomans which they had carried out in the years immediately before 1914. They exultantly sought to enforce the terms of the Treaty of Sevres of 1920 with the defeated empire; this allotted them substantial parts of Anatolia's west coast as part of a Greater Greece. Turkish armies then rallied under Mustapha Kemal, who would soon restyle himself as Kemal 'Ataturk', and in September 1922, as the routed Greeks fled, Smyrna, one of the greatest cities in the Greek-speaking world, was near-obliterated by fire (see Plate 51). In the flames perished Asia Minor's nineteen centuries of Christian culture, and ten earlier centuries of Greek civilization. A Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 overturned the agreements of Sevres, and the flood of refugees in both directions across the Aegean Sea was formalized into population exchanges on the basis of religion, not language. The effect was that religious identity transmuted into national identity: Christians became Greeks regardless of what language they then spoke, and Muslims became Turks. Within a few years, virtually all the mosques of Athens had been levelled to the ground, while the toll of church ruination in Asia Minor is still all too obvious. It was a trauma so deep that in neither country has it been possible to talk freely about refugee ancestry until very recent years.

19

The only significant exception to the general exchange, and that tragically short-lived, was Istanbul, as the wider world learned to call Constantinople in the 1930s. The Greek and Orthodox population of the city was exempted from exile, and in a commendable and surprising display of swift reconciliation, Ataturk, now leader of a Turkish Republic, and the veteran Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos sealed this agreement in 1930. Alas, the one continuing major territorial dispute between Greece and Turkey, over the future of ethnically divided Cyprus, poisoned the deal in little more than two decades. As the British sought unhappily to scramble out of colonial rule in Cyprus in the 1950s, and Greeks demanded the island's union with the kingdom of Greece, Turkish anger mounted. In 1955 the Turkish government of Adnan Menderes, on the most charitable interpretation, did nothing to stop two days of vicious and well-organized pogroms against Greeks in Istanbul; the flashpoint was the false rumour that Ataturk's birthplace in Thessaloniki (the ancient Thessalonica) had been burned down by the Greeks. There were death and rape throughout the city, and the wrecking of most of what survived of Istanbul's heritage of Greek Orthodox churches. In their wake, a Greek citizen population of some 300,000 in 1924 and 111,200 in 1934 has now been reduced to a probable figure of two thousand or less. The present Oecumenical Patriarch is a lonely figure in his palace in the Phanar. He is an international ecclesiastical statesman rightly much respected, but like his predecessors and presumably successors, he was chosen from the now tiny native Orthodox Turkish citizen population, and he does not even possess a working seminary for the training of his clergy. This near-death of Orthodox Christianity in the Second Rome is a direct result of the First World War, just as was the martyrdom of the Third Rome.

20

The only substantial Christian refuge to be created in the 1923 peace settlements at Lausanne owed its existence to the Third French Republic, which might seem a paradox until one remembers the Republicans' instrumental attitude to the Church in French colonies as an agent of French cultural hegemony.

21

France was anxious to maintain its traditional strong influence in the Middle East, which dated back to the seventeenth century, when the French Crown arrogated to itself the role of protector of Levantine Christians. Accordingly it secured the creation of a French mandate over a coastal and mountainous region described as the Lebanon, whose boundaries closely followed the strength of the population of Maronite Christians - an indigenous Church of the area, originally Monothelete in its views on the nature of Christ (see pp. 441-2), but in union with Roman Catholicism since the twelfth century. When the Lebanon later gained its independence in 1943, seizing on a moment of French disarray in the Second World War, the new republic formulated a constitution carefully designed to balance the interests of Christians against other confessional groups. It succeeded for some three decades, before unravelling in civil war; the consequences of that breakdown are still unfolding.

22

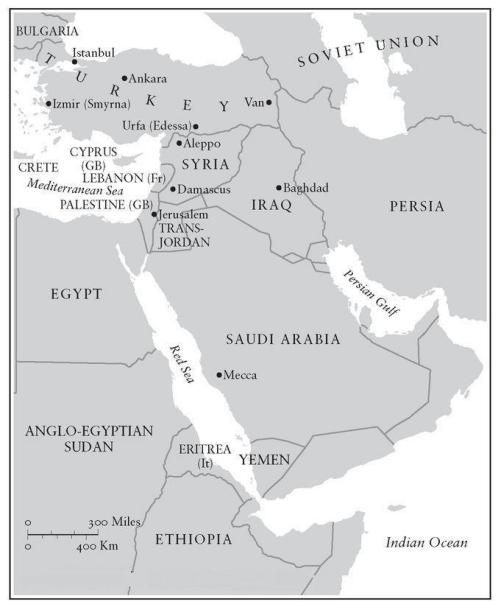

25. The Middle East and Turkey after 1923

On the eastern frontier of the new Turkish Republic, the shattered remnants of Christianity were also wretchedly caught up in international politics. Virtually all remaining Armenians fled, leaving eloquent ruins of Christian churches behind them, and the Dyophysites of the Church of the East were soon mostly in Iraq. In 1924 the Miaphysite or Syriac Orthodox people of Urfa (Edessa) faced the consequences of a successful Turkish counter-attack against French invading armies. Some stayed within the new Turkish Republic, around the holy mountains of Tur 'Abdin, where their monasteries still do their best to guard the life of prayer dating back more than fifteen centuries. Urfa itself, cradle of Christianity's alliance with monarchy, now has virtually no Christians left. Most Urfalese Syriac Orthodox fled over the new border into what was now the French mandated territory of Syria, and there in the city of Aleppo they painfully constructed a new life and preserved as much as they could from the past, including their ancient and unique musical tradition, probably the oldest in the Christian world.

The proudly maintained Syriac Orthodox church of St George in Aleppo boasts a pastiche-Assyrian bas-relief of King Abgar receiving the

Mandylion

(see pp. 180-81), as well a reproduction of the version of the

Mandylion

in Rome, presented to the congregation by the Pope himself. There are also two touching and unexpected relics of old Edessa: the church bell and a massive crystal chandelier, both given to the Edessan Christians by Queen-Empress Victoria of the United Kingdom. What trouble it must have taken to transport these unwieldy objects over the border amid the chaos and terror of 1924! Yet one can understand why. The British Empire then seemed a possible protector for an eventual return to the homeland and these would be useful symbols for an appeal to the British. The Urfalese Christians were not to know all was not what it seemed with that great imperial power.

GREAT BRITAIN: THE LAST YEARS OF CHRISTIAN EMPIRE

It was not yet publicly apparent that victorious Great Britain had been seriously undermined by the conflict of 1914-18. Its empire was augmented by virtually all of Germany's colonial possessions, together with large sections of the Ottoman Empire, mostly in the guise of 'mandates' from the newly established League of Nations, plus some client kingdoms. Alone among the major combatants in the European war, Britain retained its pre-war combination of monarchy and distinct national established Churches - Anglican in England, Presbyterian in Scotland - so its Christianity, lacking the shock of defeat or regime change, had a greater inclination to enjoy the luxury of moderation than elsewhere. Yet Britain could not escape the general trauma of the war. Sensible British politicians saw that British power was not what it had been, particularly in relation to their belated war ally, the United States. As the world's largest imperial power, Britain was bound to be affected by the general perception among colonized peoples that they had been dragged into a conflict which was not their concern. Whatever moral authority their colonial masters possessed was severely tarnished, and that did not bode well for Britain's comparatively recent worldwide imperial project. Moreover, the British Isles themselves were poisoned by a civil war which the general war had only postponed, and whose origins were religious, in Ireland. The Protestants, predominant in the north-eastern Irish counties of Ulster, refused to accept any deal for Home Rule across the island which would leave them in the hands of a Roman Catholic majority, and open violence broke out only a few months after the worldwide Armistice of November 1918.