Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (21 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

In just two respects are the first Christians recorded as having been consciously different from their neighbours. First, they were much more rigorous about matters of sex than the prevailing attitudes in the Roman Empire; they did not forget their founder's fierce disapproval of divorce. Although with Paul's encouragement Christians did move to make some exceptions to Jesus's absolute ban (see pp. 90-91), their concerns to restrict such exceptions are in sharp contrast to the relative ease with which either party in a non-Christian Roman marriage could declare the relationship to be at an end. Likewise, abortion and the abandonment of unwanted children were accepted as regrettable necessities in Roman society, but, like the Jews before them, Christians were insistent that these practices were completely unacceptable. Even those Christian writers who were constructing arguments to show how much Christians fitted into normal society made no effort to hide this deliberate difference.

27

Paul's contribution was once more ambiguous. A celibate himself, he was of the opinion that marriage was something of a concession to human frailty, to save from fornication those who could not be continent, so it was better to marry than to burn with lust. Many Christian commentators, mostly fellow celibates, later warmed to this joyless theme. Yet in the same passage Paul said something more positive: that both husband and wife have mutually conceded each other power over each other's bodies. This gives a positive motive for Christian counter-cultural opposition to divorce, but it is also striking in its affirmation of mutuality in marriage. That message has struggled to be heard through most of Christian history.

28

The other challenge to the norms of imperial society might seem to contradict even more strongly everything that we have said about Christian acceptance of the existing social order. In the Book of Acts there is an apparently circumstantial account of the Jerusalem congregation selling all the private property that its members owned in order to create a common fund for the community.

29

However, this is unlikely to have happened. The story is probably a creation of the writer's, designed to illustrate the theological point that this community was the New Israel; in the old Israel, there had supposedly been a system of 'Jubilee', a year in which all land should go back to the family to which it had originally belonged and during which all slaves should be released.

30

Probably even that original idea had never been implemented, simply remaining a pious hope, but the writer of Acts did not know that and he was making the Jerusalem Church re-enact the Jubilee of God's chosen people. Even if one decides to believe that the attempt was actually made (and it is just possible that it was), the story is frank in its admission that the scheme did not work, and two people who cheated the system were struck dead for their disobedience. Christian communism thereafter lapsed for nearly three centuries until the new counter-cultural impulse of monasticism appeared, in very different circumstances.

One has always to remember that throughout the New Testament we are hearing one side of an argument. When the writer to Timothy insists with irritating fussiness that 'I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent', we can be sure that there were women doing precisely the opposite, who were probably not slow in asserting their own point of view.

31

But their voices are lost, or concealed in texts modified much later. Up to the end of the first century, it is virtually impossible to get any perspective on the first Christian Churches other than that of writings contained in the New Testament, however much we would like to have a clearer picture of why and how conversions took place. There is a silence of about six crucial decades, during which so many different spirals of development would have been taking place away from the teachings of the Messiah, who had apparently left no written record. A handful of Christian writings can be dated to around the time of the latest writings now contained in the Christian New Testament, at the beginning of the second century, and these give us glimpses of communities whose priorities were not those of the Churches which had known Paul. For instance, one very early book about church life and organization called the

Didache

('Teaching') tells us a good deal about the worship used in the community whose life the writer was seeking to regulate, perhaps some time at the turn of the first and second centuries. It is much closer both to earlier Jewish prayers and to forms to be found in later Jewish liturgy than is perceptible in other early Christian liturgies.

32

And for all Paul's hatred of idleness, he would have been infuriated by the

Didache

's assertion that it is necessary for us to work to ransom our sins.

33

Even in the communities of Paul's tradition, we have noted change and development in the way in which Christians talked about their faith. Elsewhere, there was a whole range of possibilities for the future shape of this new religion, and no certainty as to whether any single mainstream would emerge. We have already seen how the accident of the destruction of Jerusalem had been the beginning of the end for one major possible future (see pp. 106-11). Once the Christians expanded beyond Palestine, they were meeting cultures very different from that of Judaism, especially within the Graeco-Roman world. Many converts would be people with a decent Greek education; it was only natural for them to understand what was taught them by reference to the thought of Greek philosophers. Jews had found it difficult enough to understand how the man Jesus could also be God; for Greeks, who looked to the writings of Plato to shape their understanding of God's nature, it was more difficult still. How could a Jewish carpenter's son, who had died with a cry of agony on a gallows, really be the God who was without change or passions, and whose perfection demanded no division of his substance? There were many different answers to these questions; many claimed to have particular knowledge (

gnosis

in Greek) of the truth. As early as the end of the second century, one leader destined to be seen as defining mainstream Christianity, Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyons, grouped such alternative Christianities together under a common label, talking about

gnostike hairesis

('a choice to claim knowledge'), with adherents who were

gnostikoi

. A seventeenth-century Cambridge scholar, Henry More, turned this into an English word, 'gnosticism'.

34

For all the dangers of accepting a label born in hostility, there is still usefulness in discussing these various tendencies together. Gnosticism represented an alternative future for the Church. It is probably no exaggeration to say that wherever there were Christians in the second-century world, a good many of them could have been labelled

gnostikoi

by the likes of Irenaeus.

ALTERNATIVE IDENTITIES: GNOSTICISM, MARCIONISM

Getting to know gnostics has become much easier over the last century thanks to significant archaeological discoveries, the flagship of which was at Nag Hammadi in the Egyptian desert in 1945, when a field-labourer came across a pottery jar containing fifty-two fourth-century texts in the Egyptian language Coptic.

35

They are all likely to have been translations from much older texts in other languages, principally Greek, since one of them is a section from Plato's

Republic

. Previously we had known of gnosticism through the hostile filter of such biased commentators as Bishop Irenaeus; now we can meet it in its own words. In a set of movements or tangles of thought with such variety, a search for the origins of gnosticism is unlikely to produce one answer. Much of gnosticism is a dialogue with Judaism - that is particularly true of the documents from Nag Hammadi - but the dialogue partners were not necessarily Greek. A frequent mark of gnostic attitudes was their dualism, envisaging a cosmic struggle between matched forces of good and evil, darkness and light, and that might suggest acquaintance with the dualism of Zoroastrian religion in Iran (Persia). It would be possible to argue for influence from as far away as India, in the complex of religions now known as Hinduism; after all, Alexander the Great had set Greeks into contact with India, and Roman traders continued a flourishing commerce that far east. Not all texts which belong to the gnostic literary family concern themselves with Christian problems, but despite assertions to the contrary, there seems little evidence that they predate Christianity itself.

36

Amid the different belief systems, some attributed to individuals such as Simon Magus, Cerinthus, Saturninus or Carpocrates, it is worth drawing together common tendencies.

Implicit in most gnostic systems was a distrust of the Jewish account of creation. This suggests that gnostic beliefs were likely to emerge in places with a Jewish presence and gnostics were people who found the Jewish message hard to take - maybe actually renegade Jews. Gnosticism was a creed for cultural frontiers, for instance, where Judaism interacted with Greek culture, as in Alexandria.

37

But anyone imbued with a Greek cast of enquiring mind might raise questions about Jewish insistence that God's creation is good: if that is so, why is there so much suffering and misery in the world? Why is the human body such a decaying vessel, so vulnerable even amid the beauty of youth to disease and petty lusts? Platonic assumptions about the unreality of human life, or prevailing Stoic platitudes about the need to rise above everyday suffering, could conspire with dualism from the East to produce a plausible answer: what we experience with our physical senses is mere illusion, a pale reflection of spiritual reality. If the world of senses is such an inferior state of being, then it could not possibly have been created by a supreme God. Yet the Tanakh said that it had been.

From such questions and answers, there could follow a train of thought perceptible in various forms in many gnostic documents. First, if the God of the Jews who created the material world said that he was the true and only God, he was either a fool or a liar. At best he can be described in Plato's term as a 'demiurge' (see pp. 32-33), and beyond him there must be a First Cause of all that is real, the true God. Jesus Christ revealed the true God to humanity, so he can have nothing to do with the Creator God of the Jews. Knowledge of the true God is a way to contemplate the original harmony of the cosmos before the disaster represented by the creation of the physical world. That harmony is so distant and distinct from physical creation that it involves a complicated hierarchy of beings or realities (lovingly described in mind-numbing detail and variety in different gnostic systems). Those capable of perceiving this harmony and hierarchy are often said to have been granted that privilege by a fate external to themselves: a predestination. It is these people - gnostics - whom Jesus Christ has come to save. And who is Jesus? If there can be no true union between the world of spirit and the world of matter, then the cosmic Christ of the gnostics can never truly have taken flesh by a human woman, and he can never have felt what fleshly people feel - particularly human suffering. His Passion and Resurrection in history were therefore not fleshly events, even if they seemed so; they were heavenly play-acting (the doctrine known as Docetism, from the Greek verb

dokein

, 'to seem').

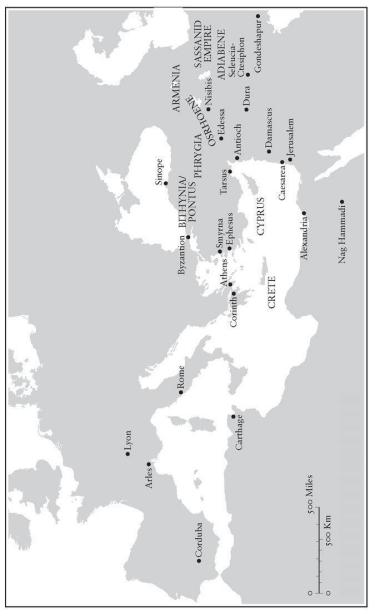

4. Christianity in the 2

nd

century CE

Equally, the real nature of the gnostic has no solidarity with the flesh of the human body; we should 'be one of those who pass by', as the Gospel of Thomas phrases it.

38

Mortal flesh must be mortified because it is despicable - or, on the contrary, the soul might be regarded as so independent of the body that the most wildly earthly excesses would not imperil its salvation. Hostile 'mainstream' Christian commentators probably took much more relish in contemplating such excesses than was justified by practice among gnostic believers. Their prurient accounts are to be taken with more than a pinch of salt. In the fourth century, Epiphanius/Epiphanios, an energetically unpleasant Cypriot bishop and heresy hunter, described gnostic rites parodying the Eucharist with the use of semen and menstrual blood.

39

In fact, the austere, ascetic strain in gnosticism is far more reliably attested than any licentiousness, and that makes it unwise to rebrand gnostic belief as a more generous-minded, less authoritarian alternative to the Christianity which eventually became mainstream. Still less plausible is a view of gnostic belief as a form of proto-feminism.

40

Gnostic hatred of the body would match very uneasily with some modern emphases on the liberating power of sexuality or feminism's physical celebration of all that it is to be female.

It is nevertheless the case that gnostics opposed the authority structures then evolving in parts of the Church, particularly in relation to one important issue: martyrdom. As we will see (see Chapter 5), this was a crucial issue in a Church which, from the death of its founder onwards, repeatedly faced bouts of persecution from the authorities of both the Roman and the Sassanian empires. One might have expected gnostic contempt for the flesh to lead gnostics to sacrifice it in martyrdom as did other Christians, but evidently they did not think the body worth sacrificing. Not only is there a total absence of stories of gnostic martyrs, but there is positive evidence that gnostics opposed martyrdom as a regrettable self-indulgence and were angry that some Christian leaders encouraged it. A text discovered at Nag Hammadi,

The Testimony of Truth

, sneers at 'foolish people, thinking in their heart that if only they confess in words, "We are Christians" . . . while giving themselves over to a human death', they will achieve salvation. The

Apocalypse of Peter

, also recovered from Nag Hammadi, says that bishops and deacons who send little ones to their death will be punished. And the recently rediscovered

Gospel of Judas

, which probably assumed Judas's name to shock followers of the bishops, condemns the Apostles as leading the Christian crowds astray to be sacrifices upon an altar. Small wonder that the Church whose leaders came to regard themselves as successors to the Apostles, and which increasingly celebrated martyrs for Christ, loathed gnostics so much.

41