Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (4 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

CONVENTIONS

Most primary-source quotations in English are in modern spelling, but where I have quoted translations made by other people from other languages, I have not altered the gender-skewed language common in English usage up to the 1980s. I am more of a devotee of capital letters than is common today; in English convention, they are symbols of what is special, or different, and, in the context of this book, of what links the profane and the sacred world. The Mass and the Rood need capitals; both their devotees and those who hated them would agree on that. So do the Bible, the Eucharist, Saviour, the Blessed Virgin and the Persons of the Trinity. The body of the faithful in a particular city in the early Church, or in a particular region, or the worldwide organization called the Church, all deserve a capital, although a building called a church does not. The Bishop of Exeter needs a capital, as does the Earl of Salisbury, but bishops and earls as a whole do not. My decisions on this have been arbitrary, but I hope that they are at least internally consistent.

My general practice with place names has been to give the most helpful usage, whether ancient or modern, sometimes with the alternative modern or ancient usage in brackets and with alternatives given in the index. The common English versions of overseas place names (such as Brunswick, Hesse, Milan or Munich) are also used. Readers will be aware that the islands embracing England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales have commonly been known as the British Isles. This title no longer pleases all their inhabitants, particularly those in the Republic of Ireland (a matter to which this descendant of Scottish Protestants is sensitive), and a more neutral as well as more accurate description is 'the Atlantic Isles', which is used at various places throughout this book. I am aware that Portuguese-speakers have long used the phrase to describe entirely different islands, and indeed that Spaniards use it for yet a third collection; I hope that I may crave their joint indulgence for my arbitrary choice. Naturally the political entity called Great Britain, which existed between 1707 and 1922, and later in modified form, will be referred to as such where appropriate, and I use 'British Isles' in relation to that relatively brief period too.

Personal names of individuals are generally given in the birth-language which they would have spoken, except in the case of certain major figures, such as rulers or clergy (like the emperors Justinian and Charles V, the kings of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth or John Calvin), who were addressed in several languages by various groups among their subjects or colleagues. Many readers will be aware of the Dutch convention of writing down names such as 'Pieterszoon' as 'Pietersz'; I hope that they will forgive me if I extend these, to avoid confusion for others. Similarly in regard to Hungarian names, I am not using the Hungarian convention of putting first name after surname, so I will speak of Miklos Horthy, not Horthy Miklos. Otherwise the usage of other cultures in their word order for personal names is respected, so Mao Zedong appears thus.

In the notes and bibliography, I generally try to cite the English translation of any work written originally in another language, where that is possible. I avoid cluttering the main text too much with birth and death dates for people mentioned, except where it seems helpful; otherwise the reader will find them in the index. I employ the 'Common Era' usage in dating, since it avoids value judgements about the status of Christianity relative to other systems of faith. Dates unless otherwise stated are 'Common Era' (CE), the system which Christians have customarily called 'Anno Domini' or AD. Dates before 1 CE are given as BCE ('before the Common Era'), which is equivalent to BC. I have tried to avoid names which are offensive to those to whom they have been applied, which means that readers may encounter unfamiliar usages, so I speak of 'Miaphysites' and 'Dyophysites' rather than 'Monophysites' or 'Nestorians', or the 'Catholic Apostolic Church' rather than the 'Irvingites'. Some may sneer at this as 'political correctness'. When I was young, my parents were insistent on the importance of being courteous and respectful of other people's opinions and I am saddened that these undramatic virtues have now been relabelled in an unfriendly spirit. I hope that non-Christian readers will forgive me if for simplicity's sake I often call the Tanakh of Judaism the Old Testament, in parallel to the Christian New Testament. Biblical references are given in the chapter-and-verse form which Christians had evolved by the sixteenth century, so the third chapter of John's Gospel, at the fourteenth verse, becomes John 3.14, and the first of two letters written by Paul to the Corinthians, the second chapter at the tenth verse, becomes I Corinthians 2.10. Biblical quotations are taken from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible unless otherwise stated.

PART I

A Millennium of Beginnings (1000 BCE-100 CE)

1

Greece and Rome (

c

. 1000 BCE-100 CE)

GREEK BEGINNINGS

Why begin in Greece and not in a stable in Bethlehem of Judaea? Because in the beginning was the Word. The Evangelist John's Gospel narrative of Jesus the Christ has no Christmas stable; it opens with a chant or hymn in which 'Word' is a Greek word,

logos

. The Word, says John, was God, and became human flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth.

1

This

logos

means far more than simply 'word':

logos

is the story itself.

Logos

echoes with significances which give voice to the restlessness and tension embodied in the Christian message. It means not so much a single particle of speech, but the whole act of speech, or the thought behind the speech, and from there its meanings spill outwards into conversation, narrative, musing, meaning, reason, report, rumour, even pretence. John goes on to name this

logos

as a man who makes known his Father God: his name is Jesus Christ. So there we read a second Greek word: Christ. To the very ordinary Jewish name of this man, Joshua/Yeshua (which has also ended up in a Greek form, 'Jesus'), his followers added '

Christos

' as a second name, after he had been executed on a cross.

2

It is notable that they felt it necessary to make this Greek translation of a Hebrew word, 'Messiah', or 'Anointed One', when they sought to describe the special, foreordained character of their Joshua. In life, the carpenter's son who died on the Cross would certainly have known Greek-speakers well, but they were the folks in the town down the road from his own Jewish hometown of Nazareth: other people, not his people. The name 'Christ' underlines the importance of Greek culture from the earliest days of Christianity, as Christians struggled to find out what their message was and how the message should be proclaimed. So the words '

logos

' and '

Christos

' tell us what a tangle of Greek and Jewish ideas and memories underlies the construction of Christianity.

How, then, did Greeks become so involved in the story of a man who was named after the Jewish folk hero Joshua and whom many saw as fulfilling a Jewish tradition of 'Anointed One', saviour of the Jewish people? We must follow the Greeks back to the stories they told of themselves, in lands which they had made home some two millennia before Joshua the Anointed One was born: mountainous peninsulas, inlets and islands which are the modern state of Greece, together with the coast now the western fringe of the Turkish Republic. Around 1400 BCE, one grouping among the Greek people was organized and wealthy enough to create a number of settlements with monumental palaces, fortifications and tombs. Chief among them was the hill-city of Mycenae in the near-island of southern Greece known as the Peloponnese, the centre of an empire which for a couple of centuries was capable of wielding power as far as the great island of Crete. Around 1200 BCE there was a sudden catastrophe, whose nature is still mysterious, which was contemporary with destruction and a collapse of culture which affected many other societies in the eastern Mediterranean; three centuries followed which have been termed a 'Dark Age'. Mycenae was overwhelmed and left in ruins, never again to be a major power. But its name was not forgotten. Mycenae was celebrated by a Greek poet who knew very little about it, but who managed to make its memory into the primary cultural experience first of Greeks, then of all peoples in the Mediterranean and then of the world which has taken on the culture of the West.

3

To talk of this 'poet' is no more than convention. There are two epic poems, the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

, traditionally ascribed to a single author called 'Homer'. It is certain that Homer lived long after Mycenae's fall around 1200 BCE - certainly not less than four hundred years later. Yet this writer or writers or band of professional singers who created the two surviving epics drew on centuries of songs and stories about that lost world. They deal with one military campaign, probably reflecting some real conflict of the remote past, in which Greeks besieged and destroyed the non-Greek city of Troy in Asia Minor (the modern Turkey). There follow the adventures of one Greek hero, Odysseus, in an agonizingly prolonged ten-year journey home. The two epics, which took shape in recitation some time in the eighth or seventh century BCE, became central to a Greek's sense of being Greek - which is strange, because the Trojan enemies are depicted as no different in their culture from the Greeks besieging them. In Asia Minor, Greeks lived close to several other peoples like the Trojans, and although in formal terms they loftily regarded all non-Greeks as

barbaroi

, speakers of languages which sounded as meaningless as a baby's 'ba-ba' babble, they were in fact keenly interested in other sophisticated cultures, particularly in two great powers which affected them: the Persian (Iranian) Empire, which came to dominate their eastern flank and rule many of their cities, and south across the Mediterranean the Egyptian Empire, whose ancient civilization stimulated their jealous imitation and made them keen to annex and exploit its agreeably mysterious reserves of knowledge.

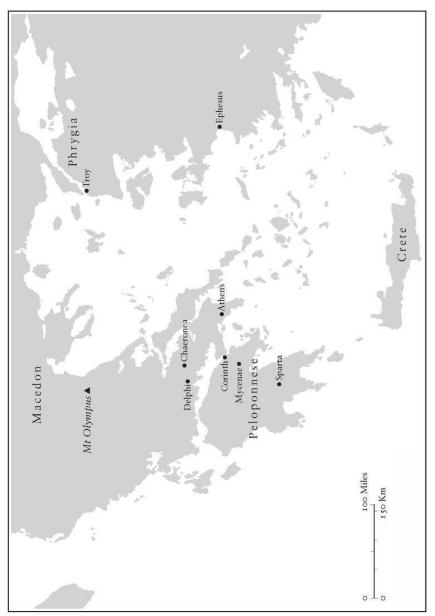

I. Greece and Asia Minor

Despite their strong sense of common identity, summed up in their word

Hellas

('Greekdom'), Greeks never achieved (and mostly did not seek to create) a single independent political structure on the gigantic scale of Persia or Egypt. They seem to have had a real preference for living in and therefore identifying with small city-states, which made perfect sense in their fragmented and mountainous heartland, but which they also replicated in flatlands in colonies around the Mediterranean. Greeks recognized each other as Greek by their language, which afforded them their common knowledge of Homer's epics, together with religious sites, temples and ceremonies which were seen as common property. Chief among the ceremonies were competitive games held to honour their chief god, Zeus, and his companions at Olympia below the mountain of Zeus's father, Kronos; there were lesser games elsewhere which likewise embodied the intense spirit of competition in Greek society. Further north was Delphi, shrine and oracle of the god Apollo, whose prophetess, dizzy and raving on volcanic fumes rising from a rock fissure, chanted riddles which any Greek might turn into guidance on worries private or public.

So, like Jews, Greeks made their religion central to their identity; and they were also the people of a book - more precisely, two books - their common cultural property. Like Jews, they borrowed a particular method of writing down their literature from the Phoenicians, a seafaring people with whom they had much commercial contact: an alphabetic script. Throughout the world, the earliest and some of the most long-lasting writing systems have been pictogrammic: so a tree could be represented by the picture of a tree. By contrast, alphabetic scripts abandon pictograms and represent particular sounds of speech with one constant symbol, and the sound symbols can be combined to build up particular words - so instead of hundreds of picture symbols, there can be a small, easily learned set of symbols: generally twenty-two basic symbols in both Greek and Hebrew, twenty-six in modern English. It was in the Greek alphabet that the earliest known Christian texts were written, and the overwhelming majority of Christians until the Roman Catholic world missions of the sixteenth century experienced their sacred scriptures in some alphabetic form. Indeed, the last book of the New Testament, Revelation, repeatedly uses a metaphor drawn from the alphabet to describe Jesus: he is Alpha and Omega, the first and the last letters of the Greek alphabet, the beginning and the end.

4

But there the cultural similarities between Jews and Greeks end: their religious outlooks were significantly different. Like most ancient societies, Greeks inherited a collection of stories about a variety of gods which they welded into an untidy description of a divine family, headed by Zeus; the Homeric legends drew on this body of myth. The gods are constantly present in the

Iliad

and

Odyssey

, an intrusive and often disruptive force in human lives: often fickle, petty, partisan, passionate, competitive - in other words, rather like Greeks themselves. It was no accident that Greek art portrayed gods and humans in similar ways, as it moved beyond its imitation of Egyptian monumental sculpture of the human form. Without knowing something of the complex iconography of this art, one would be hard put to tell the beauty of the foppish would-be dictator Alcibiades from the beauty of the god Apollo, or distinguish the nobility of the Athenian politician Pericles from that of a bearded god. The portrayal of human beings tended away from the personal towards the abstract, which suggested that human beings could indeed embody abstract qualities like nobility, just as much as could the gods. Moreover, Greek art exhibits a fascination with the human form; it is the overwhelming subject of Greek sculpture, the form in which gods as well as humans are portrayed to the exclusion of any other representational possibility.

5

The fascination extended to a cult of the living and breathing body beautiful, at least in male form, which in turn led to an insistence on athletes performing in the nude in Greek competitive games; this peculiarity baffled and horrified most other cultures, and rather embarrassed the Romans, who later tried to make themselves as much as possible the heirs of Greek culture.