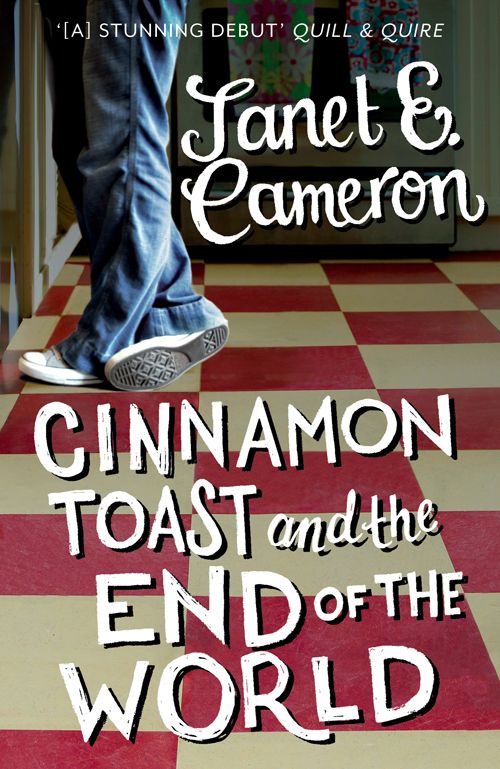

Cinnamon Toast and the End of the World

‘As with most coming-of-age stories,

Cinnamon Toast and the End of the World

has its share of light-hearted and tender moments. But it also has emotional depth … Where this novel truly excels is in

its ability to tackle several difficult subjects with clarity and conviction … Cameron doesn’t shy away from the complexity

of her material, and the effects are heart-wrenching’

Quill & Quire

, Canada

‘It’s tragic but also very funny; I laughed almost as much as I cried. This is a beautifully wrought story of those horrific

hallmarks of the teenage years … Witty, devastating, with a melancholy humour, it’s an impressive debut that begs to be read

in one emotional, tear-streaked rush’

Sunday Business Post

, Ireland

‘Cameron’s portrayal of seventeen-year-old Stephen Shulevitz is astonishingly good … A juicy coming-of-age story … but it’s

also an important read. Cameron spools out the story of Stephen so that you can feel his heartache, self-revulsion and abject

terror in painful increments’

Toronto Globe and Mail

‘A stunning debut. Funny, poignant and heartfelt’

Irish Examiner

‘[Cameron is] a talented writer, and the journey she takes us on is always pleasurable, sometimes moving, and has a lyrical

literary style … Stephen himself is a sharply drawn protagonist, his teenage view of the world suitably cynical, but underlined

with almost poetic, acute observation’

GCN

, Ireland

‘I raced through it, found it hard to put it down when I had to and wanted more when I was finished … page-turning, top-drawer

stuff’ Rick O’Shea, Bord Gáis Energy Book Club

‘Warm, witty, heartfelt and utterly engaging – a superb coming-of-age tale’

Irish News

Born in Nova Scotia, Janet E. Cameron moved to Ireland in 2005 after she met her husband, an Irish journalist, while travelling

in Japan. She has completed a Master of Philosophy in Creative Writing at Trinity College, Dublin and has been short-listed

for the Fish Short Story Prize (2008) and the Fish Short Memoir Prize (2012). She has also published an adaptation of

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

for younger ESL (English as a Second Language) learners (2010, Black Cat Publishing, Genoa). She now teaches part-time at

Dublin Business School.

Cinnamon Toast and the End of the World

is her first novel.

@ASimpleJan

HACHETTE

BOOKS

IRELAND

First published in 2013 by Hachette Books Ireland

Copyright © Janet E. Cameron 2013

The right of Janet E. Cameron to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters and places in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious. All events and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real life or real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1444 74398 2

Hachette Books Ireland

8 Castlecourt Centre

Castleknock

Dublin 15, Ireland

A division of Hachette UK Ltd.

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

To John and Nettie – with love and thanks

‘It’s not the end of the world.’

That’s what people will tell you. That’s what people will tell you when they want to say, ‘Your problems are stupid, your

reaction to them is laughable, and I would like you to go away now.’

‘Oh, Stephen, for God’s sake, it’s not the end of the world,’ my mother will say, over and over, in tones of sympathy or distraction.

Or sometimes plain impatience.

So of course if she’s ever running around looking for her keys and cursing, I’ll always tell her, ‘It’s not the end of the

world, Mom.’ And if she’s really been pissing me off, I’ll scoop the keys up from wherever she’s left them and stick them

in my coat pocket. Then I’ll settle back to watch with a sympathetic expression while she tears the house apart looking. Lost

keys? Not the end of the world.

I’m not an asshole to my mother all the time, by the way. It’s just sort of a hobby. There’s really not a lot to do in my

town.

Anyway, what I’m trying to say is, ‘not the end of the world’ is utter bullshit. Sometimes it really is the end of the world.

Sure, everything’s continuing the same as it ever did, but there’s been a shift. Suddenly you don’t know what the rules are.

People will do things that leave you

baffled. Or maybe you’ll surprise yourself, start acting like a person you don’t recognise. And you have to live in it now,

this new world. You can’t ever go back.

The end of the world doesn’t have to be floods and fires and screaming and Nostradamus and the Mayans hanging around looking

smug. It can be, say, two o’clock in the morning in the TV room in the basement with the light from the screen freezing all

the cigarette smoke into shapes like ectoplasm. My best friend Mark leans forward to light another cigarette and – boom –

the world ends.

Do you ever get these mental images – impulses, whatever – of things you wouldn’t ever do in real life? Like, suppose you’re

sitting at your desk watching the shyest girl in the whole school (Rachel Clements!) giving some kind of speech, and then

she forgets what to say next – not because she didn’t prepare or anything, just because she’s scared. So, you’re dying of

sympathy for her and clenching and unclenching your fist in nervous tension, watching this poor girl up there sweating and

stammering away. But at the same time another part of your brain is looking at the pink rubber eraser on your desk and thinking,

Throw it at her

. And you can see yourself doing it, bouncing that thing right off her forehead. Boing!

Okay, maybe it’s just me who thinks this way. But the point is, I’d never do these things. These mental blips. Who knows where

they come from or how to stop them? And if you don’t, is it the end of the world?

Anyway, it was two in the morning on Saturday night in April, and me and Mark were drinking cans that had gone all warm from

sitting in our backpacks, because it’s not like we could walk right up and stick them in the fridge in front of my mom, right?

And smoking. Smoking my mother’s brand, so if she ever finds them, I can blame it on her. Once I spent a whole afternoon with

a big pile of used butts and one of

Mom’s lipsticks, marking each one with her colour. The idea was she’d find them and think she’d gone on some kind of crazed

smoking bender and blacked out.

Didn’t work. I started feeling guilty and just threw them in the trash.

So me and Mark were in the basement, tired and stupid, laughing at the infomercials on TV, buzzing from the beer and working

our way through that red pack of Du Maurier Lights like it was some kind of assignment. These are my favourite times, but

it’s kind of hard to explain why. If you’re up that late, you’re probably alone or with somebody you’ve always known, I guess.

Or maybe it’s because there’s no light changing, so it’s as if you’re in this little corner of the world that’s safe from

time. That hour of night has always felt perfect to me. Perfect to be doing the same old shit or doing nothing at all.

Mark’s been my best friend forever, since my parents moved here when I was eight. We fell into routines that lasted years.

Saturday nights we’d go to my place and watch TV till we passed out wrapped in old sleeping bags on the two disintegrating

couches in the basement. I’d take the green one with the mildew stains and he’d take the orange one the neighbours didn’t

want. Sundays we’d wander the streets of our little town – usually high on cheap home-grown weed – and we’d end up at his

place and eat stuff spooned out of cans until I had to go back and do my homework. And Mark’s homework too, he’s not great

at school.

Neither of us ever planned this, of course. It’s not like we’d say, ‘Hey, it’s three o’clock, we better hurry or we’ll miss

getting chased out of the parking lot behind Sunset Manor by that old guy with the Sherlock Holmes hat and his fat yellow

half-blind dog who can barely bark anymore.’ But for years, if you wanted to find us at three o’clock on a Sunday afternoon,

that’s where we’d be. It happened without us

making any kind of arrangement, like birds going south for the winter know how to fly in a V.

I never even thought about whether we liked each other. I mean, how do you feel about oxygen?

That Saturday night, Mark lit another cigarette. His hand was cupped around the flame to shelter it – long habit from mostly

smoking outside – and there was a flicker of warm light on his face. Everything else was frozen in the flat white beam of

the television screen, like we were on the surface of the moon.

It reminded me of going camping with my father that one time, when I was a little kid, just before he left. We’d built a fire

together. Yellow and orange flames nodding and weaving, embers floating up. You could hear the ocean a long way off. The dark

sky opened out into trails and clusters of galaxies over our heads, and every once in a while a spark would give a satisfied

cracking pop, as if this were a live thing in front of us stretching itself with contentment. The two of us there, with our

tiny hearthglow at the edge of the world. Safe from time. I couldn’t talk. I was too happy. I didn’t want to ruin it. There

was always something that could ruin it.

A quiver of that feeling came back, watching Mark’s face, quick firelight against the bleached glare of the TV. A campfire

on the moon. Don’t say anything. Don’t ruin it.

I was hanging off the couch looking at him through the smoke, the ghost-in-a-bottle smoke.

And that’s when I kissed him.

Except of course I didn’t. It was just something that happened in my head, like seeing myself throwing erasers at Rachel Clements.

One of those strange little impulses. But so vivid and real. I could almost feel it, our teeth knocking together because I

wouldn’t know what I was doing

at first, the way our faces would look all weird being so close. He’d taste like stale beer and Du Maurier Lights and so would

I.

Nothing happened. Nobody moved. The TV continued to broadcast images of a miraculous food processor into my house. Mark kept

making sarcastic comments about it. The few streetlamps outside were still probably beaming cones of misty light against the

dark, and my mother was more than likely sleeping peacefully upstairs. Pretty quiet for the end of the world.

Mark leaned against the sofa, taking an easy swig off the beer, letting white smoke drift from his lips. In the TV kitchen,

people with big teeth and lacquered hair hovered around the food processor like they were at a party waiting for a chance

to talk to it. More blades and attachments kept getting added to the offering, fanned on a white counter before us. All for

this amazing low price.

‘Stephen? You asleep?’

Kind of a stupid thing for Mark to say because I was sitting up with my eyes open. I glanced at him quick, smoke curled around

his fingers like mist at the foot of a mountain. It hurt to breathe.

The sleeping bag was draped across my shoulders. I pulled it tighter and hauled myself to my feet.

‘I gotta go. Gotta go to the can.’

I shambled up to my room alone. The laces of the sleeping bag trailed on the floor after me.

My room was a cold place. I’d moved all my stuff in here when I was twelve, thinking I wasn’t a kid anymore and it was time

to start over. This used to be the guest room. It still felt like one. There was nothing

on the white walls but a calendar from the Royal Bank. For years I had a bikini girl on a beach pinned up by the window, the

first thing you’d see as you opened my door. She fell down a few months ago and I never bothered putting her up again.

I lay on the bed with my clothes on, knees pulled into my chest like I thought I could make myself into a dot that would get

smaller and then disappear.

I’d kissed exactly one person before, a girl at a party a couple of years ago. We were both drunk – there wasn’t a lot of

motor control involved. I remember she’d been eating ketchup chips. It was nothing like the scene I’d just imagined.

An image out of nowhere. Completely random. No idea where it came from. Oh, right. Total bullshit. When I did things like

imagine throwing erasers at Rachel Clements, I’d be surprised at myself. I would not feel half sick because I wanted it so

much.

And if I’m honest …

It wasn’t the first time I’d had these thoughts. Not the first time, not even the thousandth. Ever since I was a kid, I’d

had this stuff in my head. Ever since I was eleven or twelve I’d been telling it to go away, waiting to wake up and have it

gone.

So what was different about tonight?

It was the light on Mark’s face. It was the extra hours of day now that it was spring. It was having less than three months

of high school left. It was the TV and the smoke and the stale, flat taste of beer and my mother asleep upstairs and what

I’d just said, and what he’d just said, and the food processor on the screen, turning the resources of the earth into pureed

mush. It was everything.

I kissed him. He kissed me back. We came up for air and sat with our foreheads resting together, breathing into the silence,

hands moving

over each other’s faces. A few seconds of perfect certainty. The end. Roll the credits.

I swore and punched myself in the head.

He’d kill me.

Mark hated fags, queers, anything to do with that. How did I think he’d react if I sidled up and planted one on him? I’d end

my days with my head split open on that concrete floor in front of the TV. Nice mess of blood and brains and failure for someone

to mop up in the morning.

The stain would never go away. It would be like those children’s stories where you follow the adventures of a statue or a

tin soldier, and at the end they get thrown in the fire with the trash. After the burning, there’s always something that remains.

A heart, a little silver key. I imagined my mother would try to sell the house, have some real estate agent walking people

too quickly through the basement, trying to explain it away: the shape of my love splattered onto the floor.

Love. Is that what I’m calling it?

Remember when I said I’d never thought about whether me and Mark actually liked each other? When I said it was the same as

oxygen, that you inhale it without even knowing it’s there?

Bullshit again.

I knew I liked oxygen. In fact there was a good chance I loved it. And it occurred to me that it would be nice to be able

to breathe. Nice to be able to breathe without somebody thinking I was doing something disgusting just to spite them.

The window was a square of darkness, then it was full of cautious grey light that quietly shifted into blue. I heard a rush

of water in the sink downstairs, chirps of cupboard doors opening and closing. My mother. A smart little clack as she loaded

the tape player on the counter

with her favourite Sunday-morning tune: the Velvet Underground with ‘Sunday Morning’.

I sat on the edge of my bed and blinked into the light. I’d been sitting there for hours. When I finally got up, it felt like

I’d forgotten how to walk.

Mark was at the kitchen table with my mother, wearing my father’s old suit jacket and eating cinnamon toast.