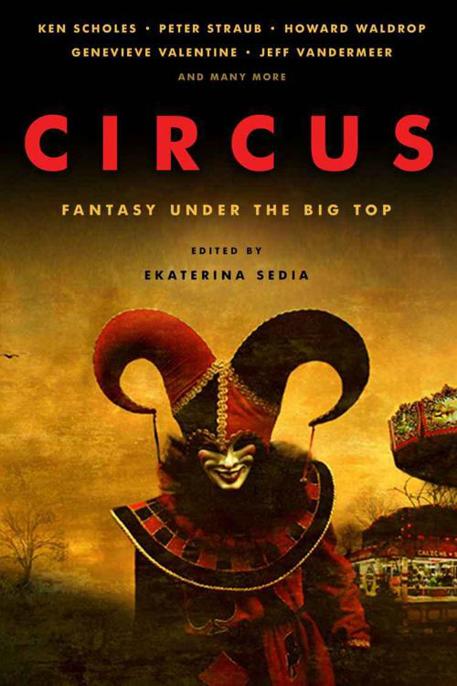

Circus: Fantasy Under the Big Top

Read Circus: Fantasy Under the Big Top Online

Authors: Ekaterina Sedia

Tags: #Fiction, #Collections & Anthologies, #Fantasy, #short story, #Circus, #Short Stories, #anthology

CIRCUS

FANTASY UNDER THE BIG TOP

EKATERINA SEDIA

Copyright © 2012 by Ekaterina Sedia.

Cover art by Malgorzata Jasinska.

Cover design by Telegraphy Harness.

Ebook design by Neil Clarke.

All stories are copyrighted to their respective authors, and used here with their permission. An extension of this copyright page can be found

here

.

ISBN: 978-1-60701-372-3 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-1-60701-355-6 (trade paperback)

PRIME BOOKS

www.prime-books.com

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

For more information, contact Prime Books at [email protected].

Contents

Introduction

by Ekaterina Sedia

Something About a Death, Something About a Fire

by Peter Straub

Smoke & Mirrors

by Amanda Downum

Calliope: A Steam Romance

by Andrew J. McKiernan

Welcome to the Greatest Show in the Universe

by Deborah Walker

Vanishing Act

by E. Catherine Tobler

Quin’s Shanghai Circus

by Jeff VanderMeer

Scream Angel

by Douglas Smith

The Vostrasovitch Clockwork Animal and Traveling Forest, Show at the End of the World

by Jessica Reisman

Study, for Solo Piano

by Genevieve Valentine

Making My Entrance Again with My Usual Flair

by Ken Scholes

The Quest

by Barry B. Longyear

26 Monkeys, Also the Abyss

by Kij Johnson

Courting the Queen of Sheba

by Amanda C. Davis

Circus Circus

by Eric Witchey

Phantasy Moste Grotesk

by Felicity Dowker

Learning to Leave

by Christopher Barzak

Ginny Sweethips’ Flying Circus

by Neal Barrett, Jr.

The Aarne-Thompson Classification Revue

by Holly Black

Manipulating Paper Birds

by Cate Gardner

Winter Quarters

by Howard Waldrop

Introduction

Most experiences change with age—the way adults perceive the book they loved as children is going to be quite different from the original wonderment. But few things change for us as universally and as dramatically as circuses. It’s true! As children, we are delighted by the simple and the obvious, we often don’t notice how depressed and depressing the animals are, how hackneyed the clowns. But as adults, we rarely managed to escape that impression—in fact, it becomes a cliche. Instead, when (and if) we go to the circuses, we are taken by the acts that require skill—trapeze and acrobats are the acts that draw the adults’ attention. We look back at our childhoods, nostalgic, and realize that there’s something in a child’s view of the circus an adult would never recapture.

But would we want to? Childhood, idealized as it is, is often naïve. We love circuses as children with unsophisticated love—but is adult sophistication necessarily inferior? Is nostalgia superior or silly? So we write stories about circuses as conversation with ourselves, more often than not—an argument, if you will, a polemic: what have we lost? What have we gained? Can we ever set foot into the same river, and if so, is it worth trying?

There is never a single answer, of course. There is never a single story. So we have collected tales of children running away to join a circus and circuses doing the same, stories of circuses not of this world (in all senses of the word), circuses futuristic, nostalgic, filled with existential dread and/or joy. Acts mundane, and spectacular, and incomprehensible. Clowns and extinct animals. Magicians and werewolves. Acrobats and living musical instruments. But always, always arguing with ourselves—because these garish, cruel places that used to be filled with joy still have a hold on us. Because we cannot help but love them—for the sake of children we were once, or for the sake of better adults we long to become. Be it a local carnival or the most celebrated circus in the world, we will always feel that tug deep inside.

—Ekaterina Sedia, New Jersey

Something about a Death, Something about a Fire

Peter Straub

The origin and even the nature of Bobo’s Magic Taxi remain mysterious, and the Taxi is still the enigma it was when it first appeared before us on the sawdust floor. Of course it does not lack for exegetes: I possess several manila folders jammed to bursting with analyses of the Taxi and speculations on its nature and construction. “The Bobo Industry” threatens to become giant.

For many years, as you may remember, the inspection of the Taxi by expert and impartial mechanics formed an integral portion of the act. This examination, as scrupulous as the best mechanics could make it, never found any way in which the magnificent Taxi differed from other vehicles of its type. There was no special apparatus or mechanism enabling it to astonish, delight, and terrify, as it still does.

When this inspection was still in the performance—the equivalent of the magician’s rolling up his twinkling sleeves—Bobo always stood near the mechanics, in a condition of visible anxiety. He scratched his head, grinned foolishly, beeped a tiny horn attached to his belt, turned cartwheels in bewilderment. His concern always sent the children into great gouts of laughter. But I felt that this apparent anxiety was a real anxiety: that Bobo feared that one night the Einstein of mechanics, the Freud of mechanics, would uncover the principle that made the Magic Taxi unique, and thereby spoil its effectiveness forever. For who remains impressed by a trick, once the mechanism is exposed? The mechanics grunted and sweated, probed the gas tank, got on their backs underneath the Taxi, bent deep into the motor, covered themselves with grease and carbon so that they too looked like comic tramps, and at the end of their time, gave up. They could not find a thing, not even registration numbers on the engine block, nor trade names on any of the engine’s component parts.

In appearance it was an ordinary taxi, long, black, squat as a stone cottage, of the sort generally seen in London. Bobo sat at the wheel as the taxi entered the tent, his square behatted head flush against the Plexiglas window that opened onto the larger rear compartment. This was empty but for the upholstered backseat and the two facing chair-seats. It was the very image of the respectable, apart from the sense that Bobo is not driving the taxi but being driven by it. Yet, though nothing could look so mundane as a black taxi, from the first performance this vehicle conveyed an atmosphere of tension and unease. I have seen it happen again and again, consistently: the lights do not dim, no kettle drums roll, there is no announcement, but a curtain at the side opens, and unsmiling Bobo drives (or is driven) into the center of the great tent. At this moment, the audience falls silent, as if hypnotized. You feel uncertain, slightly on edge, as if you have forgotten something you particularly wished to remember. Then the performance begins again.

Bobo does strikingly little in the course of the performance. It is this modesty that has made us love him. He could be one of

us

—fantastically dressed and pummeling the bulb of his little horn when confused or delighted. When the performance concludes, he bows, bending his head to the torrential applause, and drives off through the curtain. Sometimes, when the Taxi has reached the point where the curtain begins to sweep up over the hood, he raises his white-gloved, three-fingered hand in a wave. The wave seems regretful, as if he wishes he could get out of the Taxi and join us up in the uncomfortable stands. So he waves. Then it is over.

There is little to say about the performance. The performance is always the same. Also, it differs slightly from viewer to viewer. Children, to judge from their chatter, see something like a fireworks display. The Taxi shoots off great exploding patterns that do not fade but persist in the air and enact some sort of drama. When pressed by adults, the children utter merely some few vague words about “The Soldier” and “The Lady” and “The Man with a Coat.” When asked if the show is funny, they nod their heads, blinking, as if their questioner is moronic.

Adults rarely discuss the performance, except in the safety of print. We have found it convenient to assume a maximum of coincidence between what we have separately seen, for this allows our scholars to speak of “our community,” “the community.” Exegetes have divided the performance into three sections (the Great Acts), corresponding to the three great waves of emotion that overwhelm us while the Taxi is before us. We agree that everyone over the age of eighteen passes inexorably through these phases, led by the mysterious capacities of the Magic Taxi.

The first act is The Darkness. During this section, which is quite short, we seem to pass into a kind of cloud or fog, in which everything but the Taxi and its attendant becomes indistinct. The lights overhead do not lessen in intensity, they do not so much as flicker. Yet the sense of gloom is undeniable. We are separate, lost in our separation. At this point we remember our sins, our meagerness, our miseries. Some of us weep. Bobo invariably sobs, the tears crusting on his white makeup, and blats and blats his little horn. His painted figure is so akin to ours, and yet so foolish, so theatrical in its grief, that we are distracted from our own memories. We are drawn up out of unhappiness by our love for this tinted waif, Bobo the benighted, and the second act begins.

This section is known as The Falling because of the physical sensations it induces. Each of us, pinned to the rickety wooden benches, seems to fall through space. This is the most literally dreamlike of the three acts. As the sensation of falling continues, we witness a drama that seems to be projected straight from the Taxi into our eyes. This drama, the “film,” is also dreamlike. The drama differs from person to person, but seems always to involve one’s parents as they were before one’s own birth. There is something about a death, something about a fire. Our own figure appears, radiant, on the edge of a field. Sometimes there is a battle, more often there is walking upward on a mountain path through deciduous northern trees. It is Ireland, or Germany, or Sweden. We are in the country of our greatgreat-great grandfathers. We belong here. At last, we are at home. It is the country that has been calling to us all our lives, in messages known only to our cells. In it we are given a brief moment to be heroic, a long lifetime to be moral. This drama elates us and prepares us for the final section of the performance, The Layers.

The beam of light from the Taxi disappears into our eyes, like a transparent wire. When our eyes have been filled by the light, the Taxi, Bobo, the sweaty lady sitting on your right, and the man in the blue turtleneck directly in front of you, all of them disappear. The first sensation is that of being on the fuzzy edge of sleep; then the layers begin. For some, they are layers of color and light through which the viewer ascends; for some, layers of stone and gravel and red sandstone; an archeologist I know once hinted to me that in this part of the performance he invariably rises through various strata of civilizations, the cave dwellers, the hut builders, the weapon makers, the iron makers, until he is ascending through towns and villages that had been packed into the earth. I, for my part, seem to rise endlessly through scenes of my own life: I see myself playing in the leaves, making snowballs, doing homework, buying a book—I cry out with happiness, seeing the littleness of my own figure and the foolishness of all my joys. For they are all so harmless! Then the external recurs again before us, Bobo waves driving through the curtain, and it is finished.

In the first years, when the Taxi was of interest to only a few, we did not worry much about meanings. We took it as spectacle, as revelation—a special added attraction, as the posters said. Then the scholars of C—— University issued their paper asserting that Bobo’s Taxi was the representation of “common miracle,” the sign that the world is infused with spirit. The scholars of the universities of B—— and Y—— agreed, and issued a volume of essays entitled

The Ordinary Splendor.