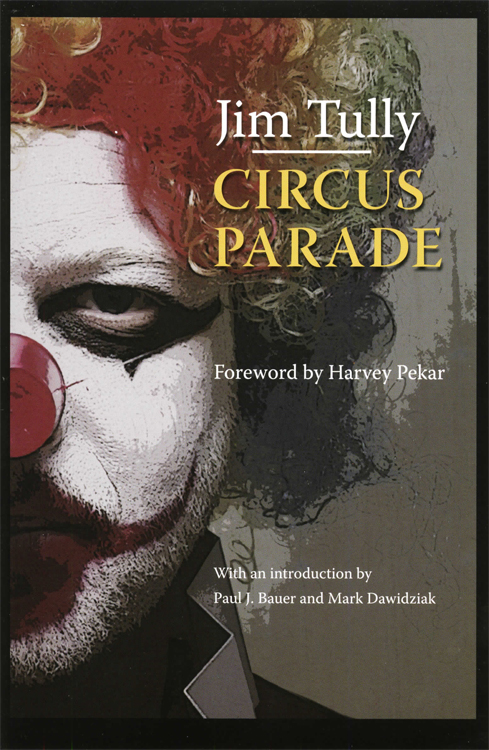

Circus Parade

Authors: Jim Tully

PARADE

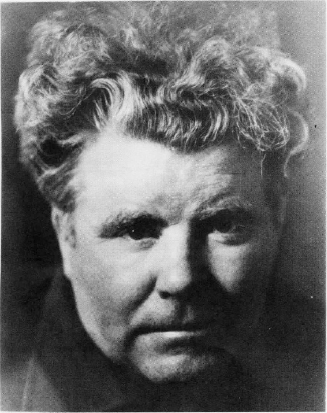

Jim Tully, 1886â1947

ircus

PARADE

By JIM TULLY

Illustrated by WILLIAM GROPPER

Edited by Paul J. Bauer and Mark Dawidziak

Foreword by Harvey Pekar

Black Squirrel Books

KENT, OHIO

© 2009 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2009000938

ISBN

978-1-60635-001-0

Manufactured in the United States of America

First published by Albert & Charles Boni, Inc., 1927.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tully, Jim.

Circus parade / by Jim Tully; illustrated by William Gropper; edited by Paul Bauer and Mark Dawidziak; foreword by Harvey Pekar.

p. cm.

ISBN

978-1-60635-001-0 (pbk.: alk. paper) â

I. Gropper, William, 1897â Bauer, Paul, 1956â III. Dawidziak, Mark, 1956â IV. Title.

PS

3539.

U

44

C

57 2009

813'.52âdc22 | 2009000938 |

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

13Â Â 12Â Â 11Â Â 10Â Â 09Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 5Â Â 4Â Â 3Â Â 2Â Â 1

To

H. L. MENCKEN

GEORGE JEAN NATHAN

DONALD FREEMAN

JAMES CRUZE

and

FREDERICK PALMER

CIVILIZED COMRADES

IN THE

CIRCUS OF LIFE

Introduction by Paul J. Bauer and Mark Dawidziak

Jim Tully was one of the fine American novelists to emerge in the 1920s and '30s. He gained this position with intelligence, sensitivity, and hard work. Born in St. Marys, Ohio, in 1886 to Irish parents, Tully was placed in an orphanage at the age of six when his mother died. He ran away at eleven, working as a farmhand and then becoming a hobo until age twenty-one. Despite his troubled childhood, he managed to give himself a good literary education. He haunted libraries and read Balzac, Dostoyevsky, Gorky, Twain, and his early idol, Jack London, among others.

After working as a newspaper reporter in Akron, Tully settled in Hollywood and worked for a time as a press agent for Charlie Chaplin. He wrote or cowrote more than two dozen volumes, not all of them published, until his death in 1947. By that time, his work had gained the praise of H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan.

Published in 1927,

Circus Parade

deals with the time Tully worked as a laborer for a traveling circus. He did this because the state of Mississippi, where he was located, treated hoboes so badly. “In other parts of the United States a tramp is not molested if he keeps off railroad property,” Tully wrote in

Circus Parade

. In Mississippi, however, a price is put on his head. With no money to pay the vagrancy fine, he is put to work at twenty-five cents a day and can spend several years as a virtual slave of the state.

Circus Parade

consists of a series of vignettes, rather than a tight narrative structure. The first chapter, for example, has to do with a black lion tamer. Tully notes that most lion tamers he's encountered have been black. In

Circus Parade

and in other books, Tully pays special attention to blacks. He sympathizes with them, although he also seems puzzled by them. Anybody who loved the Irish as much as Tully might have a hard time fully understanding another minority group, but Tully was the exception. Consider his attitude in

Blood on the Moon

(1931) toward Joe Gans, the great African American lightweight boxer of the early twentieth century. Gans was obviously a bright guy with a good sense of humor. He wasn't easy for Tully to categorize. Tully wrote, “His features were more Semitic than Negroid” and “if the art of pugilism can reach genius, Gans was so gifted. The elements were blended in himâstamina, caution, cunning, swift and terrible execution.”

Blood on the Moon

joins

Circus Parade

as one of Tully's finest achievements.

Circus Parade

contains some of Tully's most memorable characters, black and white. The book differs from his other autobiographical works as the plot revolves around other circus employees, not himself. For example, the owner of the circus was a seventy-three-year-old carny veteran named Cameron, a clever con artist who was extremely cheap. Cameron was not well liked by most of his employees. Nonetheless, they all stuck together when they were attacked. Their rallying cry was “Hey, Rube!” as they hurried to fight oil workers or townspeople or anyone looking for a fight.

Tully also writes about people in the side show, like “The Moss-Haired Girl,” a beautiful young woman who dyed her hair green and was the object of wonder to many customers. Another circus attraction was Lila, the four-hundred-pound German strong woman. She was a stellar attraction, but then she started buying fashionable clothes and reading romance novels. Her desire for a man led to tragic results.

I wondered if Tully had actually known Lila, or whatever her name was. But the important thing is that he made her and the scene believable, both with his economical, straightforward, no-nonsense writing style and his inclusion of many details that give the whole story the air of truth. He does this often. No matter how crazily violent or fantastic his stories are, you accept them as nonfiction. Tully makes the improbable seem true. But then he must have had some amazing experiences in his hobo years. He was even a prizefighter for a time.

Where does Tully fit among the writers of his time? His work was relatively popular and received much critical praise during his lifetime. He created an original style, blending a spare writing approach with some fantastic stories, often about lower-class life with slang dialects and phonetic spellings (he had a very good ear). Tully was somewhat anticipated by Stephen Crane in tone, however, particularly in

Maggie: A Girl of the Streets

(1893). Crane wrote about life in the New York City slums, using slang and phonetic spelling: “âRun, Jimmie, run! Dey'll get yehs,' screamed a retreating Rum Alley child. âNaw,' responded Jimmie with a valiant roar, âdese Micks can't make me run.'” I can find no evidence that Tully ever read Crane or was influenced by him; the similarities could very well be coincidental. But Crane, who died in 1900, obviously anticipated Tully, whose first novel was published in 1922. Tully read so much that a number of writers probably influenced his style, whether he realized it or not.

Regarding Tully's huge appetite for literature of all kinds, it's interesting to note that he had a real respect for at least some avant-garde writing, as his sensitive and perceptive chapter on James Joyce in

Beggars Abroad

illustrates. The fiction-reading public these days is about as confused about Joyce as it was when

Ulysses

was published.

As for Tully's legacy, perhaps it is most clearly seen in detective stories beginning about 1930. His work often had a tough quality, but it is genuine, not affected like Ernest Hemingway's.

The Kent State University Press should be praised for publishing long-out-of-print works by this important Ohio writer. I hope we will see a renewal of interest in his work and additional volumes published, including Tully's writing about Hollywood. He wrote an early novel about the film industry (

Jarnegan

, 1926), an unpublished biography of Charlie Chaplin, and many uncollected movie articles for magazines and newspapers.

In one interview, Tully claimed he had “the best library in Hollywood.” I believe it.

Paul J. Bauer and Mark Dawidziak

Jim Tully (June 3, 1886âJune 22, 1947) was an American writer who won critical acclaim and commercial success in the 1920s and '30s. His rags-to-riches career may qualify him as the greatest long shot in American literature. Born near St. Marys, Ohio, to an Irish immigrant ditch-digger and his wife, Tully enjoyed a relatively happy but impoverished childhood until the death of his mother in 1892. Unable to care for him, his father sent him to an orphanage in Cincinnati. He remained there for six lonely and miserable years. What further education he acquired came in the hobo camps, boxcars, railroad yards, and public libraries scattered across the country. Finally, weary of the road, he arrived in Kent, Ohio, where he worked as a chainmaker, professional boxer, and tree surgeon. He also began to write, mostly poetry, which was published in the area newspapers.

Tully moved to Hollywood in 1912, when he began writing in earnest. His literary career took two distinct paths. He became one of the first reporters to cover Hollywood. As a freelancer, he was not constrained by the studios and wrote about Hollywood celebrities (including Charlie Chaplin, for whom he had worked) in ways that they did not always find agreeable. For these pieces, rather tame by current standards, he became known as the most-feared man in Hollywoodâa title he relished. Less lucrative, but closer to his heart, were the dark novels he wrote about his life on the road and the American underclass. He also wrote an affectionate memoir of his childhood with his extended Irish family, as well as novels on prostitution, boxing, Hollywood, and a travel book. While some of the more graphic books ran afoul of the censors, they were also embraced by critics, including H. L. Mencken, George Jean Nathan, and Rupert Hughes. Tully, Hughes wrote, “has fathered the school of hardboiled writing so zealously cultivated by Ernest Hemingway and lesser luminaries.”

Circus Parade

, completed in March 1927 and published that summer, was Jim Tully's fourth book. After the Hollywood novel,

Jarnegan

(1926), he returned to his memories of the road. In many ways,

Circus Parade

may be viewed as a sequel to

Beggars of Life

, his 1924 bestseller about his years as a road kid. Indeed, they became the first two volumes in what Tully later called his underworld books.

Drawing on his own time as a circus roustabout, Tully's first story of circus life appeared in

Vanity Fair

in 1925 with chapters from what would become

Circus Parade

appearing in 1926 in

Liberty

and later in

Vanity Fair

. Introductory blurbs on the dust jacket were provided by Harry Hansen (“the small town circus as it was, in straight-hitting fashion”) and William Allen White (“hard, terrible realism that will shock the life out of unsophisticated readers”). Early Tully booster George Jean Nathan was especially enthusiastic: “Tully has got the rawness of life as few American writers have been able to get it, and, with it, a share of poetry and of very shrewd perception ⦠a view of mortals and of their sawdust hearts that will not soon vanish from the memory.”

Tully dedicated

Circus Parade

to Nathan and Mencken, editors of

The American Mercury

, Donald Freeman, managing editor of

Vanity Fair

, and Tully's Hollywood pals James Cruze and Frederick Palmer. Mencken's editorial contributions went beyond friendship, and Tully inscribed the Sage of Baltimore's copy: “To H. L. Mencken with high appreciation to one who made the book possible.”

If Tully appreciated Mencken's assistance, Mencken certainly appreciated Tully's hard-edged, straightforward style.

Some writers, like musicians, seem to write to an internal metronome. Tully wrote to the click-clack-click-clack of the rails, which became the unadorned, crisp, staccato rhythm of his prose. And like the view from an open boxcar,

Circus Parade

consists of a series of vignettes, each flashing by without reflection or rumination before the next scene is in front of the reader.

The narrator of

Circus Parade

is as memorable as his counterpart in

Beggars of Life

, but while

Beggars of Life

is a panorama of great memories,

Circus Parade

is a panorama of great characters. And those characters populate the tents and wagons of an outfit grandly billed as Cameron's World's Greatest Combined Shows. Despite the name, no one would confuse Cameron's ten-car collection of carnies, freaks, and other sawdust celebrities with The Greatest Show on Earth.

The characters that populate

Circus Parade

range from the sympathetic and innocent through the merely distasteful and cold-hearted to the cruel and black-hearted.

The carnies include:

â¢

Bob Cameron, the troupe's “sardonic and brutal” owner

â¢

his wife, a greedy crone affectionately known as “the baby buzzard”

â¢

John Quincy Adams, the guileless black clown who performs in whiteface

â¢

the Moss-Haired Girl, a sideshow attraction so named for her green hair and based in part on an Irish-Indian girl Tully had once loved

â¢

Slug Finnerty, the one-eyed barker or “spieler” who'd done time in the penitentiary for the rape of a young boy and was “the leader of the gang of crooks”

â¢

Lila, the kind-hearted, lonely, 400-pound “Strong Woman” who whiles away her nights reading romance novels

â¢

Blackie, amoral and bestial, a roustabout, heroin addict

The boyhood dream to run away with the circus ran deep in the American psyche. “When a circus came and went,” wrote Mark Twain in

Life on the Mississippi

(1883), “it left us all burning to become clowns.”

Looking at the lions in their cages, Tully is struck by his own sense of freedom. His gaze shifts to the crawlersâlegless men strapped to small, wheeled platforms who moan with pain to boost their take from the crowd. It is a clear message. Tully has not set out to write a romantic story of a boy joining the circus. He knows too well its seamier side.

Circus Parade

is as far removed from

Toby Tyler

as

The Maltese Falcon

is from

The Hardy Boys

.

Instead, over the course of the book, Tully paints a picture of life at the edgesâearthy, wolfish, and brutal. “A circus is, or was,” Tully writes, “generally a canvas nest of petty thieves and criminals among the lower gentry.” The lambs among them repeatedly fall to the predators.

While good and evil play out in

Circus Parade

, Tully is not especially interested in questions of morality and immorality. Rather, he is fascinated by amorality. Tully makes a distinction between the amoral Blackie and the greedy and immoral circus bosses. Tully's character passes one rainy night playing cards with other roustabouts when Blackie stands up, pulls a gun, and robs them. Then, in grand pirate tradition, Blackie “red-lights” the men, forcing them to jump from the moving train. Tully's character falls back on his hobo instincts, scrambles to his feet, catches the last car, and pulls himself back on-board. He has no interest in revenge. “I had no love for the red-lighted men. Rather, I admired Blackie more. Neither did I blame him for red-lighting me. A man had once trusted another in my world. He was betrayed.”

Blackie lived by a code. It may have been nothing more than the basic code of the animal to survive, but it was honest and without pretense. Just survive.

With

Circus Parade

, Tully's dreams of popular and critical acceptance were met. Sales were strong, the Literary Guild quickly contracted for a 16,000-copy reprint, Hollywood sought the film rights, and the comments from friends and formal reviews were strong, even ecstatic. One reviewer noted that the book was not for those “easily shocked.” “But,” he continued, “there is something other than bare naturalism in this book, a glowing overtone of humanity, comprehension, and pity that cannot be too highly prized.”

A teenage James Agee wrote that

Circus Parade

was “remarkable chiefly for its nakedness of style, and for uncovering the most abysmal brutality I've even imagined could exist.”The Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen took note of the book's several black characters. “This book,” he wrote, “will destroy some illusions, but that is the natural function of truth.” And years later, Langston Hughes wrote Tully that he was on his third reading of the book.

There were, predictably, naysayers. Father Francis Finn, S.J., who recalled Jim as a scullery boy at St. Xavier's College in Cincinnati, recognized Tully's literary talents but decried what he saw as Tully's paganism and gloom. He further found Tully's work “offensive to Christian modesty” for which he blamed the bad company of hoboes in general and Charlie Chaplin in particular.

Critics found the chapter in which a young black girl is mercilessly degraded especially outrageous. Tully later noted that he recalled the incident from his circus days and put it to paper with little embellishment.

Adding to the furor, the Brooklyn Public Library prohibited its copy from circulating. A library in Idaho, according to one Tully correspondent, circulated the novel but with the offending chapter ripped from the book. And in Boston, the Watch and Ward Society declared an outright ban.

Circus Parade

joined a Watch and Ward list of banned books that included Sherwood Anderson's

Dark Laughter

, William Faulkner's

Mosquitoes

, Theodore Dreiser's

An American Tragedy

, Sinclair Lewis's

Elmer Gantry

, and Hemingway's

The Sun Also Rises

.

In a letter to H. L. Mencken, whose

American Mercury

had run afoul of Boston's Watch and Ward Society the previous year, Tully joked that he planned to go to Boston and pass out copies of the book to the hoboes, as they were “the only cultivated men I could find in the city.”

While Tully could laugh off criticism from Boston, a bad review from St. Marys stung. Tully's hometown newspaper, the

Evening Leader

, in an editorial titled “Filth in Books,” claimed to be “unpleasantly surprised that so much dirt could be packed between the covers of a book.” In the view of the

Evening Leader, “Circus Parade

was written without excuse, except perhaps of making money.” While acknowledging that Tully was a “clever writer” and “knows of what he writes,” the newspaper could see no justification for exposing the public to such sordid subject matter. Tully's hometown paper widened its condemnation to include

Beggars of Life

and

Jarnegan

, advocating that the publication of all such books be prohibited.

Hurt and angered by criticism from home, Tully responded in a letter to the editor published in October 1927. Tully cited Mencken's comparison of him to Gorky and noted he and the great Russian writer of the underclass have something else in common: both come from hometowns ashamed of them. Clearly old wounds had been opened. “When I was a hungry boy in St. Marys,” he wrote, “I got no understanding. I am getting none now.” If his goal was getting rich, he argued, then he might adopt the maudlin style of the then-popular novelist Harold Bell Wright. Instead, “I write the truth.” Had he taken his own counsel, he might have stopped there, but some bridges were made to be burned. In words that soured relations with many in his hometown for the rest of his life, Tully noted that “St. Marys is still in the same mental rut that it was in when I had the sadness of living there.” Nor would he deal in the “childish terms of small Ohio towns.” The sarcasm of the paper's response dripped off the page. “Jim, you are great. Wonderful! You and Gorky!”

Not content to get the last word but once, the

Evening Leader

returned to the subject of its famous native son in November by noting and reprinting the poor review of

Circus Parade

that appeared in a South Bend paper. The central criticism of the Indiana reviewâthat

Circus Parade

presented an inaccurate picture of circus lifeâechoed the view of Eugene Whitmore in

The Bookman

. While acknowledging that

Circus Parade

had been “hailed by dozens of critics as a masterpiece of realistic writing,” Whitmore charged that the book was “no more than old-fashioned melodrama, minus the lily-white hero and heroine.” And, Whitmore continued, “Tully paints in dark colors, with no lightening contrasts.”

On the first point, Whitmore was half-right. There are no heroes in

Circus Parade

, but a hero's struggle is an essential element of melodrama. Whatever

Circus Parade

was, it wasn't “old-fashioned melodrama.” On the second point, there can be no argument. Tully did paint in “dark colors.” If Whitmore had come to the book for sweetness and light, he had come to the wrong place and the wrong writer.

In building his case that

Circus Parade

was not realistic, Whitmore relied on what he saw as factual errors about circus life. He chided Tully for faulty geography, quoting Tully for writing, “we traveled as far inland as Beaumont, Texas,” when, in fact, Beaumont is a port town on the Gulf of Mexico. Tully's meaning of westward travel is clear, however, when he is correctly quoted: “We had journeyed along the Gulf of Mexico and as far inland as Beaumont, Texas.”

Whitmore, who claimed “a lifetime of contact with circuses,” also objected to “Tully's ignorance of the nomenclature of circus tents,” the description of loading and unloading the circus train, the troupe's travel in the south before the “cotton has been picked and marketed,” and, in his view, other implausibilities and misstatements of fact. Clearly,

Circus Parade

was not to the liking of old circus men.

James Stevens, whose acclaimed novel about Paul Bunyan and lumber camps had appeared in 1925, wrote Burton Rascoe, the editor of

The Bookman

, to protest Whitmore's attack on

Circus Parade

. Twain's nonfiction

Life on the Mississippi

, he noted, was roundly denounced by “old steamboat men,” and lawyers quibbled with Dreiser's

An American Tragedy

. A novelist, Stevens argued, is certainly allowed to sacrifice “fact for effect.”