Class (40 page)

Mozart, Haydn, Vivaldi and Purcell are upper-class composers. Brahms, Mahler, Schubert and Beethoven are upper-middle. Tschaikovsky, Grieg and Mendelssohn are lower-middle.

Samantha would simply love to sing in the Bach Choir. Her mother adores Gilbert and Sullivan. Howard Weybridge has a few classical records:

Peer Gynt

, the Moonlight Sonata and ‘Cav-and-Pack-them-in’. He is also ‘very active’ in amateur operatics. Jen Teale enjoys

Down Your Way

and

Your Hundred Best Tunes.

Mr Nouveau-Richards likes the cuckoo in the Pastoral Symphony and claps between movements. Tracey-Diane sways from side to side when she plays ‘The Lost Chord’ on the pianola. Mrs Definitely-Disgusting likes Mantovani and Ron Goodwin, and thinks Verdi’s Requiem is a ‘resteront’.

In a recent survey it was discovered that people who own their houses prefer classical music, but people in council houses prefer pop. One suspects that the house-owners claimed to prefer classical music because they felt they ought to, because it seems more upper-classical than pop. After all the announcers do talk in ‘posh’ voices on Radio Three while the disk jockeys on Radio One and Capital all sounds like yobbos.

The Radio Three voice is not in fact upper-class at all, it is Marghanita Laski/Patricia Hughes sens-it-ive, which involves speaking very slowly and deliberately to eradicate any trace of a regional accent, with all the vowel sounds, particularly the ‘o’s, emphasized: ‘vi-oh-lins’, ‘pee-ar-

noes

’, ‘Vivald-ee’, ‘ball-

ay

’. The pronunciation of foreign composers and musical terms is also far too good. The upper classes have frightful accents when they talk in a foreign language. As Harry Stow-Crat’s mother once admonished him: ‘Speak French fluently, darling, but not like them.’

17 TELEVISION

Why did you choose such a backward time and such a strange land?

If you’d come today, you’d have reached a whole nation.

Israel in 4 B.C. had no mass communication.

Jesus Christ Superstar

Light years above everyone else are the telly-stocracy. The man in the street is far more impressed by Esther Rantzen than by Princess Anne. ‘When I go to the country,’ said Reginald Bosanquet a year or two ago, ‘I am more revered than the Queen.’ Our own local telly-stocrat, David Dimbleby, is particularly impressive. With a famous television father, he is second-generation telly and looks like founding a dynasty:

‘Once in Royal David’s Putney,’ sing the children in the street.

To show the influence these people have, a couple I know were watching Angela Rippon read the news one evening when the wife admired her dress.

‘Why not see if they’ve got one like it in Bentalls?’ said her husband.

So off she went next day and found something very similar.

‘Every time Angela appears on television,’ confided the sales girl, ‘we get people pouring in here trying to buy what she was wearing.’

It’s not just the telly-stocracy. Everyone who appears on television is somehow sanctified, albiet temporarily, with a square halo. It doesn’t matter how inept one is, credit improves dramatically in the High Street. If ever I appear, my enemies in a nearby council estate, who usually shake their fists at me because of my cat chasing dogs, start waving and saying, ‘Saw you last night. What’s Eamonn really like?’

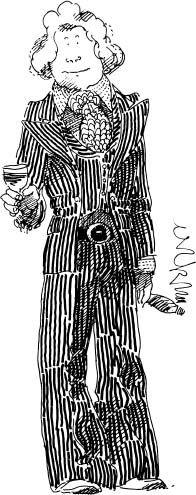

A member of the telly-stocracy

Our particular part of Putney is known locally as Media Gulch because so many television stars, actors and journalists live here. One can only keep one’s end up if one has the television vans outside one’s house at least once every two months, plus a gutted bus where all the crew break every couple of hours for something to eat and hordes of men with prematurely grey hair and he-tan are draping plastic virginia creeper over the porch to give an illusion of spring.

But apart from creating a telly-stocracy, the looming presence of television has done more to change our social habits than anyone realizes. When commercial television appeared in the ‘sixties, it was hailed by Lord Thomson as the great leveller. As a new and thrilling medium, it seemed to epitomize the change from a rigid class system. In fact it has reinforced it. Every day 23 million eyes stay glued to the commercial television screen. Advertising in particular makes people dissatisfied with life. The initial effect is to encourage them to go out and buy consumer goods, formerly enjoyed only by their social superiors. As they acquire these, and feel themselves to be going up in the world, television becomes their social adviser. It tells them where to go on their hols, what car they should own, which wines to order, what fuel to burn, what furniture to buy. ‘Win Ernie Wise’s living room,’ screams the

T.V. Times

, ‘Win Ian Ogilvy’s bedroom’—nearer, my God, to thee! In fact, it is most unlikely that Ernie Wise or Ian Ogilvy has anything to do with those rooms; they took their cheques and left the furnishing to some lower-middle-class advertising stylist with a penchant for repro tat. (Someone once unkindly described Bruce Forsyth’s house as being filled with the sort of things people couldn’t remember on the conveyor belt of The Generation Game.)

Even more pernicious, television gives lots of advice on attitude and behaviour. Mrs Definitely-Disgusting doesn’t hit the roof any more every time Dive and Sharon come charging in with mud all over their newly washed jeans. She gives a crooked smile and reaches for the Daz. She feels guilty if her kitchen isn’t spotless, and discontented if it isn’t a modern one. If a horde of children drop in she doesn’t tell them to bugger off, she fills them up with beefburgers. Mr D-D knows now not to talk about ‘Cock-burn’s port’ and to pronounce Rosé as Ros-

ay

.

Television, too, has created a new type of plastic family: smiling, squeezy mums, woolly-hatted Dads playing football and crumbling Oxo cubes, plastic dogs leaping in the air, plastic children stuffing baked beans, lovable plastic grans who are befriended by pretty air-hostesses but are never sick. ‘Why aren’t we as happy as they are?’ asks Mrs Definitely-Disgusting. ‘It isn’t fair.’

Television increases aspiration but underlines the differences, and has thereby produced strong ‘Them’ and ‘Us’ polarization. Mr D-D can pile up goods till he’s blue in the face, but it’s still difficult for him to improve his status, cross the great manual/non-manual divide and join the Martini set.

Television has created a battered victim, rendered insensible by a ceaseless bombardment of mindless hypocrisy. It is hardly surprising that so many children can’t read or write, that few people can be seen in the streets of towns or villages after dark. The nation is plugged in. They are watching Big Brother.

Television forms the basis of nearly all conversations in offices and pubs. (A friend spent a week at Butlins on advertising research and said people talked permanently in television jingles, one person beginning one, the next ending it.) Worse still is the effect on debate and argument, because of the law that requires television to be politically fair, all arguments end in compromises not in conclusions.

‘You have the highest quality television in the world,’ said an American to Professor Halsey who wrote the recent Reith lectures on class, ‘but

I Claudius

would be impossible in midstream America. Nowhere else in the Western World does the élite have the confidence both to indulge its own cultural tastes and also believe these should be imposed on the masses.’

Not surprising too that the Annan Committee on Broadcasting expressed concern, after months of research, that people were being brainwashed by middle-class values. Too many characters talk in non-working-class accents. There are not enough working-class heroes on the screen.

The report also complained that various kinds of upper-class characters—royalty, aristocracy, jet set, etc—occurred in 22 per cent of all programmes, almost always in significant roles. Middle-class characters occurred in 56 per cent of the programmes and 76 per cent of them were significant to the plot. But the working-classes only occurred in 41 per cent of the programmes and in only 71 per cent were significant. In terms of their occurrence, in relation to the population at large, middle-class, and even more, upper-class individuals are over-represented on television drama, and when they appear, they are likely to appear in important and attractive roles. This creates envy.

T.V. Times

and

The Radio Times

(to a lesser extent) are also obsessed with class. In every interview a person’s character is analysed in relation to his background. In one issue of the

T.V. Times

alone we are told that Tessa Wyatt loathes publicity and doesn’t want to strip in films because of her inhibited, middle-class background, that John Conteh ‘the fourth born of a family of ten from a yellow painted council house’ has risen by working-class guts, and is now a rich man with ‘a waterfall in the garden of his luxury Bushey (Hertfordshire) home’. And when Katie Stewart visited Emmerdale Farm, she found them ‘gathered for dinner—that’s what most people who live in the north of England call the midday meal’.

The Queen, Robert Lacey tells us, watches television to find out about her subjects. One suspects she’s an addict like the rest of us.

Princess Margaret also watches it the whole time. A friend went to dinner when she was married to Lord Snowdon and the television stayed on the whole time before dinner, was carried into the dining-room and placed on the table on which they were eating, then carried back into the drawing-room immediately they’d finished.

Evidently the whole Royal family was livid about the spate of royal sagas, particularly

Edward and Mrs Simpson

, not because the events portrayed were so near the knuckle but because the actors playing them or their relations were, they considered, so common. The Queen Mother was evidently most upset by the girl who played her.

‘Oh that reminds me, Bryan. Christine’s just had her first understain.’

But half the fun of television is looking for the slip-ups. The supposedly upper-middle-class mother in the

House of Caradus

talking about ‘when your father was in active service’ or Christina in

Flambards

saying ‘Pardon’ and ‘Ever so’. Recently when Thames serialized one of my novels they got the classes quite cockeyed. It was supposed to be about the Scottish upper classes, but almost the first shot was of a wedding cake with a plastic bride and groom on top. The hero kept calling the heroine ‘woman’; the heroine returned from her honeymoon landing on a Western Isle wearing a hat and high heels, and everyone waved their arms frantically in the air during reels at a ball.

Rebecca

, on B.B.C. 2 recently, almost got it right. The only time they appeared to slip was when Maxim talked about ‘Cook’, and when some very unpatrician extras appeared in the ball.

‘It’s impossible to make extras behave with any authority,’ said one of the cast. ‘They always look as though they’d got their costumes from Moss Bros.’

The young in particular have been so brain-washed by the egalitarian revolution that, according to one casting director, it’s impossible to find an actor in his thirties who can convincingly play upper-middle to upper-class Englishmen of half a century ago. They lack the assurance, the bearing, the tone of voice. Recently a duke’s daughter auditioned for a part in Thames Television’s dramatization of a Nancy Mitford novel. Not having a clue who she was, the director passed her over. ‘What was wrong with her?’ asked the producer afterwards. ‘She was too middle-class,’ replied the director.