Classic Christmas Stories (15 page)

Read Classic Christmas Stories Online

Authors: Frank Galgay

by Jim Furlong

I

LOVE CHRISTMAS IN all its aspects. I am endlessly

fascinated and in a way haunted by it, and the older I get the more I marvel and

wonder at the hold it has over our society. It is that concept of “wonder” that

is really the central theme of the Christmas season, and each passing year has

me deep in thought on how its celebration endures. What strikes me as odd is

that, as the years drift by, this yuletide introspection seems to grow.

Why is that? Why does Christmas gnaw away at me? It may be linked to the idea

of the Christmas feast being one of those major signposts in our lives that

lasts through what are sometimes called “the ages of man.” Your first day of

school or your graduation or your first job or your first love are all signposts

from a particular period in your existence. While memories are intense, they are

of a single specific event. Christmas, however, spans the aforementioned “ages

of man” and provides continuity and important linkage between past and

present.

We all remember the Christmas of our childhood and the assorted Christmases

that have accompanied us along the path to where we are today. In just a few

years Christmas evolves from something looked forward to with eager anticipation

to something else altogether. As the rolling years accumulate it becomes a

season that we view often through

life’s rear-view mirror

smiling back at the string of Christmases that strung together have become our

life story. You can start a great conversation at any Christmas gathering by

asking everyone about what may have been his or her favourite toy or his or her

special Christmas memory. Eyes grow gently moist as people dip deep into their

memory banks and, with the story of a sometimes simple gift, rekindle that most

precious of aspects of the human spirit—wonder. That is Christmas.

For me there are the memories of Toyland and church. I am old enough to

remember what were really the first “Toylands.” They were part of the great

mercantile houses of Water Street like Bowring Brothers, Ayre and Sons, and all

the rest. Going “downtown” was part of the Christmas pilgrimage that took Mom

and my brother not only to department stores but to McMurdo’s or The Sweet Shop

for fries or a chocolate sundae. Looking in the windows at the Christmas

displays of the big stores was an important part of that as well. The department

stores employed window dressers then, whose job it was to put forward the best

commercial “foot” of the business for passersby to see. The Royal Stores and The

London New York and Paris competed, as did Bowrings, Ayres, and others. Silver’s

Jewellery on Water Street west stood out. It had a mechanized Santa display that

made a couple of generations of little eyes open wide. I think that Santa played

piano, although the clickety-clack of the tracks of time have made some memories

“gauzy.” Window shopping plus a trip to one of half a dozen different raffles on

Water Street were part of the adventure. “Two for five! Four for ten! Thirty

cents a dozen!” I sense readers’ heads nodding in agreement, because it is a

distinct St. John’s memory I share with many. It is part, really, of a postwar

St. John’s Christmas outing where a family that had been frugal throughout the

year was rewarded with a brief venture into the “world of purchase.”

Toylands at “the shops” were a world of Mechano sets and guns and holsters and

games of Ludo, Snakes and Ladders, and Parcheesi, and Blow Football, which was

two straws and a plastic soccer ball. I remember well that little educational

toy called The Magic Robot. He rested on a piece of mirrored glass and had a

wand and you pointed the wand at a current events or history question on a piece

of printed cardboard on the game and, when the robot moved to another mirror, he

pointed at the correct answer. “What animal is known as ‘The ship of the

desert’?” “The camel is known as ‘The ship of the desert.’” It all worked on a

polarized magnet and within a

few days you had all the

answers memorized, but it was still wonderful and on the cutting edge of

technology, because these were the days when the only computers in the world

were ones that had either cracked “the Enigma code” in World War II or provided

results on “The Sixty Four Thousand Dollar Question” in our single-channel

television universe.

Of course, all the toys of Toyland didn’t come to you at Christmas, but you did

probably get one or two, because this was Christmas and it was, as it is now, a

season of excess. All things being relative. There were electric trains, and

microscopes, bubble makers, kaleidoscopes, and Monopoly games, and even some

toys that have endured, like Tinker Toys and Etch-a-Sketch and Slinky. They

stand almost as giants honoured in some toy pantheon.

Going around to look at the Christmas lights in “town” was very much part of

our secular Christmas ritual. It was like looking in the window of someone who

had “more.” My aunt had a car and our family didn’t, so we went with her. Most

homes didn’t have Christmas lights except a candle in the window, but a few,

like the Pippy property on Waterford Bridge Road, did. The Sanatorium lights

with the big Christmas tree and the Christmas Seal sign was always a highlight,

as was their manger scene. The “San, ” as it was called, was a threat from many

a parent. “If you don’t eat your carrots you’ll end up in ‘the San’ before you

are fifteen.”

Christmas was a season you knew was different on many levels from the others,

and it wasn’t just in toys and lights. Some foods made their way into the home

to let you know it was Christmas. There were chocolates, of course. A nice box

of Ganongs where you slyly pushed on the chocolate to find “a hard one.” There

were other candies too, like Liquorice Allsorts. It was a very British candy, as

were “chicken bones” and “humbugs.” Nobody liked them and they were always the

last ones left. There were salted nuts, maybe even cashews, and special baked

goods that only appeared at Christmas, like cheese straws and marmalade cookies,

dark cake and cherry cake. There was, of course, turkey and ham and Christmas

pudding and those Christmas crackers with the tiny prize inside. There was

Purity raspberry syrup that for reasons I never understood only made it into the

house at Christmas, although it is sold year-round. Come to think of it, I only

buy it at Christmas now. Olives fit into that once-a-year category, and so do

boxes of fancy English biscuits.

Accompanying all of that was religion. We were deep then in

the grip of Holy Mother Church, for better or for worse. In those days our house

had an Advent wreath just as we had one in school. I doubt if there is a house

in all of Newfoundland that has one now. There were four candles and each was

lit in succession during the four weeks leading up to Christmas. They, like

vigil lights placed before statues of the Blessed Virgin in our homes, have

vanished, no doubt because there are regulations that would promptly get your

fire insurance cancelled if you used them. We also had a “crib” which was used

every year. The individual pieces were wrapped carefully in paper, and bringing

them out for the season was ceremonial and very much a part of our family

liturgy. On Christmas Eve, of course, we went to midnight Mass at St. Patrick’s

in the heart of the west end. There were five priests there then. In those days,

to go to Holy Communion, as it was called, you had to fast from midnight the

night before. You would be pretty hungry by Mass at eight in the morning, but

for midnight Mass you only had to fast for an hour or so. Mass was all in Latin

then from start to finish. Christmas carols and Gregorian chant. I still know

“Adeste Fideles” in Latin from start to finish. With bells and incense, it all

added to the great mystery of the whole thing. There were some people in church

that hadn’t been there since last year. They were “Christmas Christians, ” but

that didn’t matter because they too were welcome.

After Mass we went home and ate. We called it steak, but it wasn’t really. It

was stewing beef that had been simmering on the stove during the time we were in

church. Mass is over, your stomach is full, and stretching ahead the prospect of

Christmas morning and opening presents. We were told that only uncivilized

people opened presents on Christmas Eve. “Back-laners, ” Mom called them. That’s

an ancient name that references an imagined St. John’s social structure and the

maze of little intersecting streets that crawl up the hill from New Gower Street

to Lemarchant Road.

Where has it all gone? Well, I don’t think it has gone anywhere. We still go to

Mass Christmas Eve. We have our own rituals and traditions, from bringing out

the “crib” to getting the Christmas tree to putting the angel on the top of the

tree. It is the same angel that was in my home when I was boy. On our tree once

again this year, an old set of lights that has been in our family for sixty

years. That continuity is important. It is part of ritual and celebration.

In Christmas we still, as we always did both in an out of

church, wrestle with the eternal questions. They are about the birth of an

Infant in a manger and about how Santa Claus gets down the chimney. Those

questions are both valid because they speak to the human capacity and ability to

inquire and to take us places beyond the known universe. They speak to the

notion of wonder and miracles.

Certainly the Christmas season itself is a miracle. It brings out the best in

we much-flawed humans. At Christmas people are simply nicer to one another. The

police will tell you that even criminals take a break. There is very little

crime because of Christmas, because people turn their minds, however briefly, to

something else. Our “gentler angels” reveal themselves. Call me simple-minded,

but I think on some important level the clerk in the store that says “Merry

Christmas” or the waiter at the restaurant that wishes me “the best of the

holidays” really means it. They wish me well at Christmas. So it is that we go

from being children, to having children, to raising children, and to finally

letting them go. Our lives measured by time passages and through all of that

there is Christmas. Through all of that there is a happy and holy season where

there is celebration and plenty and, as there has been for two thousand years or

so . . . wonder.

by L. A. W.

C

HRISTMAS HAS THE SAME meaning to every true English heart, the same secret mystery surrounds the word, whether

it be kept under the burning sun of India or Australia, or amid

the ice and snow of the frozen North.

The children dream of that strange, mysterious being called Santa

Claus, who comes at night when all are asleep, and gently, noiselessly,

leaves his gifts, and then withdraws as silently as he came.

The maiden dreams of the holly, with its bright red clusters, and the

mistletoe, with its pale green leaves and pure white berries, fit emblem of

a maiden’s heart.

Christmas in the Far North is, however, very different from that spent

in warmer climes. I will try and describe one of the many pleasant ones

I have spent on the coast of Labrador, far away from the old land I used

to call “home.”

Christmas and Easter are the two great events of the year, and for

them great preparation is made. The house is thoroughly cleaned from

top to bottom, and everything made bright and shining.

For weeks before Christmas the days are counted by the young people,

and the thermometer constantly inspected to see if it is getting colder; when

down to zero there is great delight, as the ice will be good for travelling.

The girls are whispering together, and a great part of the time are

invisible, except at meals. There are no shops or stores near in this part

of the world, so the presents and keep-sakes, little tokens of love and

friendship, must be made by their own fair fingers, and as they are not to

be seen by the owners till the Christmas morning, it requires some little

manoeuvring to keep them out of sight.

The boys, meantime, are busy learning their recitations, making

new strings for their “rackets” (snow-shoes), painting up the coach-box,

making a new whip, which is quite a long affair, as it is made of seal-skin

prepared in a particular manner.

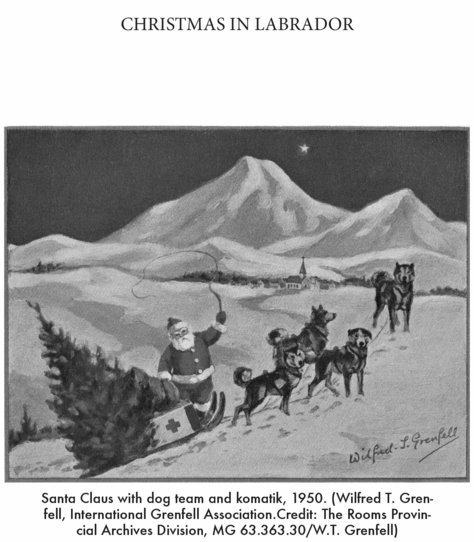

The little Esquimaux Andrew has painted his “komatik” (or sleigh),

and has put on the finishing touches, in the shape of two diamonds made

of whalebone. And now all is ready, the morning so long wished for

dawns at last, the gifts have been presented, loving greetings exchanged,

and the joy of the young folks is complete. Dinner is served, the dogs are

harnessed, the “komatik” brought to the door and, enveloped in buffalo,

bear, and other skins, with many injuctions to the drivers to take care of

the rapids, the rosy, laughing crowd are tucked in the coach-box, and,

with one crack of the whip and signal to the head dog, they are gone.

Their destination is the Mission House, seven miles away. Half-way

on the road stands a large comfortable house, with a huge wood-pile

before the door; this is “grandmama’s, ” and here the merry band get out.

Grandmama is waiting for them. She, too, has not been idle. She has some

little present made by her own busy fingers, for each of them, and as they

enter the door, each rosy cheek is pressed in turn in her loving embrace,

the packages are opened, the little gifts presented, and again, with many

good wishes, the happy group are once more

en route

, this time for the

Mission House. Here the good pastor is ready with a cordial greeting,

and he, too, has something for each boy and girl. During the long winter

evenings, and often far into the night, he has stolen time from his busy

labors to paint a bookmark, or Christmas card, a souvenir which in after

days and, perhaps, far away scenes, will bring back the memory of his

loving words and earnest, faithful counsel to those giddy young folks.

The decorations of the school-room are also the work of his busy

fingers and untiring brain.

The journey thus far over, the festivities of the evening commence,

consisting of songs, recitations,

tableau vivant

, and last, but not least, a

monster Christmas tree. So the time passes, and all too quickly comes the

hour of returning.

The journey home, however, is very different from the outward one, for

during the night a heavy gale of wind has arisen and broken up the outside

bay, and it will be necessary to wait two or three days to allow the ice to get

thick enough to travel on. At length the start is made, and for a while the

progress is smooth and safe enough, but when they come to the outside bay,

it is not yet frozen over, so there is nothing for it but to take a boat. They

are accordingly transferred from the warm “komatik” to the open boat, and

now the struggle commences. It is bitterly cold, and as the boat moves slowly

through the water the ice is forming fast and threatens to hold it in its deadly

embrace, while the strong current is drifting rapidly seaward.

Our party, however, had met at the mouth of the river a group of

four or five young men from the Westward, also bound down for the

Christmas festivities—tall, stalwart fellows, every one of them. With

steady hands they grasp the oars, and while some of them break the ice,

the others pull through slowly, and with great difficulty, till at length the

firm ice is again reached, the party transferred to the “komatik, ” and

soon the welcome lights of home shine out, as, wearied and cold and

numbed they reach the open door. Quickly they are divested of their furs

and wraps, the half frozen limbs rubbed and warmed; the supper table

is soon spread: a huge haunch of venison, stuffed and roasted, a large

piece of beef, roast partridges, mince pies, bowls of bake-apple and red

berry preserve, and the famous Christmas pudding being some of the

good things under which the large table groans again, and to which our

travellers do ample justice, the last few hours’ vigorous exercise of the

muscles contributing not a little to their enjoyment of the repast.

The table is again cleared, and then the young folks engage in games,

which bring the merry Christmastide to a close.

On the morrow, the party, numbering twenty or more, disperse to

their homes, the quiet moon shines out with that peculiar brilliancy

known only in these regions of intense frost, and that strange silence,

broken only by the sound of the aurora borealis flashing through the still

night air, or the ice cracking in the landwash, settles down over the scene.

So ends one of our Christmastides in the Far North.