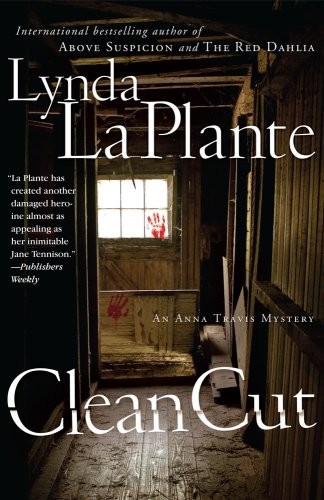

Clean Cut

Authors: Lynda La Plante

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Mystery Fiction, #Murder, #Women detectives - England - London, #England, #Murder - Investigation, #Travis; Anna (Fictitious Character), #Women detectives, #london, #Investigation, #Police Procedural, #Women Sleuths

The Red Dahlia

Above Suspicion

The Legacy

The Talisman

Bella Mafia

Entwined

Cold Shoulder

Cold Blood

Cold Heart

Sleeping Cruelty

Royal Flush

Prime Suspect

Seekers

She’s Out

The Governor

The Governer II

Trial and Retribution

Trial and Retribution I

Trial and Retribution II

Trial and Retribution III

Trial and Retribution IV

Trial and Retribution V

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2007

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright © Lynda La Plante, 2007

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

® and © 1997 Simon & Schuster Inc. All rights reserved.

The right of Lynda La Plante to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Gray's Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-84739-508-5

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual people living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

This book is dedicated to the memory of a truly special young man. The handsome, flame-haired Jason McCreight, I still mourn for him and perhaps I always will. Jason was a constant support, especially for my writing. During the first rough drafts of

Clean Cut

he was encouraging and played a very important role making notes and queries for me to answer. One paragraph he underlined, and when I asked him why, he smiled and said, ‘because I liked it’. Whether this meant something special I will never know, but this was the paragraph:

Anna wept because deep down in her heart she knew, unlike her father, she would not be able to deal with it. If Langton did not recover, there would be a difficult transition and she doubted she had the strength to confront it, well not now, she would have to at some later date. In the meantime she intended to give him every possible incentive to be able to deal with whatever the future held. From now on, even though she did love him, she would take it day by day, and pray that she never had to walk away from him until he was strong enough to deal with it.

My gratitude to all those who gave their valuable time to help me with research on

Clean Cut

, in particular Lucy & Raff D’Orsi, Professor Ian Hill (pathology), Dr Liz Wilson (forensics), and Callum Sutherland for all their valuable police advice.

Thank you to my committed team at La Plante Productions; Liz Thorburn, Richard Dobbs, Pamela Wilson and Noel Farragher. For taking the weight off my shoulders to enable me to have the time to write and for running the La Plante Productions company. Thanks also go to Stephen Ross and Andrew Bennet-Smith and especially to Kara Manley.

To my literary agent Gill Coleridge and all at Rogers, Coleridge and White, I give great thanks. I give special thanks for their constant encouragement. To my publishers Ian Chapman, Suzanne Baboneau and to everyone at Simon & Schuster, especially Nigel Stoneman. I am very happy to be working with such a terrific company.

DAY ONE

A

nna was in a foul mood. He had not turned up for dinner. Work commitments sometimes took precedence, obviously–she knew that–but he only had to call and she would understand. In actual fact, she had put understanding of their profession right at the top of the pluses on her list. It was a Friday and she had a long weekend due; they had planned to drive out to the country and stay overnight at a lovely inn. It was unusual for them both to have time off, so it made it even more annoying that he had not phoned. She had left messages on his mobile but did not like to overkill, as it was possible he was on a call out; however, she knew that he was meant to be winding down the long and tedious enquiry he had been on for months.

Anna scraped the dried food off the plate into the bin. Tonight had not been the first time by any means and as she sat, tapping her teeth with a pencil, she tried to calculate just how often he had missed dinner. Sometimes he had not even turned up at all, but had gone to stay at his own flat. Although they did, to all intents and purposes, live together, he still kept his place in Kilburn; when he was on a particularly pressing case and working round the clock, he used it rather than

disturb her. It was not a bone of contention; sometimes she had even been relieved, although she never admitted it. He also liked to spend quality time there with Kitty, his stepdaughter from his second marriage. All this she could take in her stride, especially if she was also up against it on a case of her own.

They did not work together; they had not, since they became an item. This was partly due to the Met’s once unspoken rule that officers were not to fraternize, especially if assigned to the same case. It had bothered Langton more than Anna, but she had understood his reservations and was quietly relieved that, since the Red Dahlia case, they had been allocated to different enquiries. They had a tacit agreement not to bring work home to each other; she adhered to it, but Langton was often in such a fury that he started swearing and cursing as soon as the front door opened. She had never brought this up, but it had become very one-sided. As he ranted and railed about his team, about the press, about the CPS–about anything that had got under his skin that day–he rarely, if ever, asked what her day had been like. This went onto the list of minuses.

Anna went to stack the dishwasher; God forbid he ever considered moving his cereal bowl from the sink to the dishwasher. He was often in such a rush to get out in the morning that she would find coffee cups in the bedroom, the bathroom, as well as something she had grown to really detest: cigarette butts. If there wasn’t an ashtray within arm’s reach, he would stub his cigarettes out in his saucer or even in his cereal bowl; to her knowledge, he had never, since they had been together, ever emptied an ashtray. He had never taken the rubbish out to the bins either, or washed a milk bottle and put it

out; in fact, he almost used her Maida Vale flat like a hotel. She was the one who sent the linen to the laundry, collected it and made up the beds with fresh sheets; then there was the washing and the ironing. He would leave their bedroom like a war zone: socks, underpants, shirts and pyjama bottoms strewn around the room, dropped where he had stepped out of them. There was also the slew of wet towels left on the floor in the bathroom after his morning shower, not to mention the toothpaste without its cap. She had brought up a few of these things and he apologized, promising he would mend his ways, but nothing had changed.

Anna poured herself a glass of wine. The list of minuses was now two sheets long; the pluses just a couple of lines. Now she got onto bills. He would, when she asked, open his wallet and pass over a couple of hundred pounds, but then often borrowed it back before the end of the week! It wasn’t, she concluded, that he was tight-fisted; far from it. It was just that he never thought. This she knew: often he was complaining about his flat being cut off because he’d forgotten to pay his own bills. When he was at home, he ate like a starving man, but had never once accompanied her to do a grocery shop. The plus, if you could call it a plus, was that he did say anything she placed in front of him was good, when she knew her culinary expertise left a lot to be desired. He also downed wine at a rate of knots, and never went to bed without a whisky; this particular minus was underlined. Langton’s drinking had always worried her. He had, on various occasions, gone on one of his drying-out periods; they usually lasted a week or so and were often done to prove that he was not, as she had implied, bordering on alcoholism. He could get into quite an angry mood if she brought it up,

insisting he needed to wind down. She kept on writing, however; the drinking at home was one thing, but she knew he also hit the pub with his cohorts on a regular basis.

Anna emptied her wine glass and poured another; she was getting quite piddled herself, but was determined that when he did come home, it was time for a long talk about their relationship. She knew it was unsatisfactory: very obviously so, when she read through her list. What invariably happened when she had previously attempted to try to make him understand how she felt, was that the plus side of their life together made it never the right moment. He would draw her into his arms at night, so they lay wrapped around each other. She adored the way he would hold her in the curve of his body and nuzzle her neck. His hair was usually wet from the shower and he smelled of her shampoo and soap; many nights, he would shave before coming to bed, as his dark shadow was rough to her skin. His lovemaking left her breathless and adoring; he could be so gentle and yet passionate, and was caring and sensitive to her every whim–

in bed

…

Langton’s presence filled her small flat from the moment he walked in the front door until the moment he left, and without him there was such an awful quiet emptiness. Sometimes she enjoyed it, but never for long; she missed him, and loved to hear him running up her front steps. She was always waiting as he let himself in, opened his arms and swung her round as if he’d been away weeks instead of a day. He then dropped his coat and briefcase, kicked off his shoes, and left a trail of discarded garments all over the place as he went into the bedroom to shower. He always showered before

they had dinner; he hated the stink of cells, incident rooms and the stale cigarettes that clung to his clothes. After his shower, he would put on an old navy-blue and white dotted dressing-gown and, barefoot, go into the lounge to put the television on. He never settled down to watch any single programme, but would switch between news items and the various soaps that he hated with a vengeance. As she cooked, he would yell from the lounge what a load of crap was on TV, then join her to open the wine. Perched on a stool, he would talk about his day: the good, the bad and, sometimes, the hideous. He always had such energy and, in truth, when he did discuss his cases, she was always interested.

DCI Langton had a special gift; anyone who had ever worked with him knew it and, on the two occasions Anna had been assigned to work on his team, she had learned so much. In fact, living with him made her even more aware of just what a dedicated detective he was. He always looked out for his team and she, more than anyone, knew just how far he had gone to protect her when she had not obeyed the rules. Though he often bent them himself, he was a very clever operator; he had an intuitive mind, but his tendency to be obsessive made him tread a very dangerous line. During the eighteen months they had lived together, even when he had been hard at work all day, she had often seen him working into the early hours, going over and over the case files. He never missed a trick and his prowess at interrogation was notorious.

Anna sighed. Suddenly all her anger over him missing dinner and her urge to make lists evaporated; all she wanted was to hear his footsteps on the stairs and then his

key turn in the lock. After all, she knew he was wrapping up a murder enquiry; doubtless he had just gone for a celebratory drink with the boys. She finished her wine and took a shower, getting ready for bed. She wondered, as it was so late, whether he had gone to his own flat. She rang, but there was no reply. She was about to call his mobile again when she heard footsteps on the stairs. She hurried to be there waiting for him, when she froze, listening. The steps were heavy and slow; instead of hearing the key in the front door, the bell rang. She hesitated; the bell rang again.

‘Who is it?’ she asked, listening at the door.

‘It’s Mike–Mike Lewis, Anna.’

She hurried to open the door. She knew instinctively something was wrong.

‘Can I come in?’

‘What is it,’ she asked, opening the door wide.

DI Lewis was white-faced and tense. ‘It’s not good news.’

‘What’s happened?’ She could hardly catch her breath.

‘It’s Jimmy. He’s over at St Stephen’s Hospital.’

Langton and his team had just charged the killer of a young woman. When the man had put in the frame two other members of his street gang, Langton, accompanied by Detectives Lewis and Barolli (close friends, as well as members of his murder team), had gone to investigate. As they approached the two men, one had knifed Langton in the chest, then slashed his thigh. He was in a very serious condition.

By the time the speeding patrol car reached the hospital, Anna had calmed herself down: no way did she want him to see her scared. As she hurried through

the corridors leading to the Intensive Care Unit, she was met by Barolli.

‘How is he?’ Lewis asked.

‘Holding his own, but it’s touch and go.’ Barolli reached out and squeezed Anna’s hand. ‘Bastard knifed him with a fucking machete.’

Anna swallowed. The three continued to the ICU.

Before Anna was allowed to see him, they met with the cardiothoracic surgeon. The weapon thankfully had missed Langton’s heart, but had caused severe tissue damage; he also had a collapsed lung. She could hardly absorb the extent of the injuries: she felt faint from shock and had to continually take deep breaths. Both Lewis and Barolli were pale and silent. It was Lewis who asked if Langton would make it.

The surgeon repeated that he was in a very serious condition and, as yet, they could not estimate the full extent of his injuries. He was on a ventilator to assist his breathing; his pulse rate was of deep concern.

‘Will I be allowed to see him?’ Anna asked.

‘You can, but only for a few moments. He’s sedated, so obviously will not be able to talk. I must insist that you do not enter the Unit, but look through the viewing section. We cannot afford any contamination; he’s obviously in a very vulnerable state.’

Langton was hardly visible among the tubes. The breathing apparatus made low hissing sounds as it pumped air into his lungs. Anna pressed her face close to the window; the tears she had tried so hard to contain flowed, yet she made no sound. Lewis had a protective arm around her shoulders, but she didn’t want it. She wanted to be alone; she wanted to be closer to Langton–above all, she wanted to hold him.

Anna remained at the hospital all night; Lewis and Barolli returned to their homes.

The next morning, Langton went into relapse. Again, she could only watch helplessly as the medics worked to resuscitate his heart. Drained by anxiety, and both emotionally and physically exhausted, she finally returned home after being told he was stable.

DAY TWO

She was back again by mid-morning to sit and wait, in the hope she might be able to at least see him closer. The hours passed at a snail’s pace; she constantly stood in the Intensive Care viewing room, watching the array of doctors and nurses tending to him. She hadn’t cried again since first seeing him; she now felt as if she was suspended in a state of panic. Her head ached and she felt physically sick. It was Lewis who made her go and get something to eat; he would stay watching.

The hospital café was almost empty. She ordered a coffee, some soup and a roll. She hardly touched any of it, but picked at the bread, rolling it into small balls. She could hardly take it in: Langton might die. It was just so unthinkable that such an energy force could suddenly be terminated. Closing her eyes, she twisted her trembling hands in her lap, whispering over and over, ‘Please don’t let him die. Please don’t let him die.’

When Anna returned to Lewis, he was sitting on a hard-backed chair, reading the

Daily Mail

. The headline read:

Top Detective Knifed

. Lewis had numerous other papers, all running the attack on the front page. It had created

considerable political impact: the number of knife attacks in London had been escalating. Langton had become one of the first police officers to be wounded, and by an illegal immigrant; the list had mostly comprised murdered schoolkids until now. The news programmes all covered the knife amnesty arranged by the Met; the summation was that there were hundreds of thousands of armed kids in schools alone.

Lewis folded the paper, sighing. ‘Makes me sick, reading these articles. What they don’t say is that those two bastards are still being hunted, but with no luck tracing them. At least we got the bugger.’

‘The man who attacked him?’

‘No, the case we were working on–murder of a prostitute, Carly Ann North. He was picked up trying to slice her head off. A local cop caught him at it, rang for back-up and when they turned up, the two so-called pals did a runner.’

‘Is that when you were brought in?’

‘Yeah. Jimmy questioned him–he’s a twenty-five-year-old Somali illegal immigrant called Idris Krasiniqe. He served six months in prison for robbery and was then released! Bloody mind-blowing, the fucker was let loose. He’s now held at Islington station. Without Jimmy, I’ll have to handle the trial.’

‘These other men that were with him–have you got any trace on them at all?’

‘No. We went to try to find them after we had a tip-off from Krasiniqe. That was when it happened.’

Anna could see Lewis was physically shaking; he kept swallowing, as if he was having trouble catching his breath.

‘So, this tip-off?’ she prompted.