Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness (9 page)

Read Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

“Auntie Glug told me Martin was smelly and had a prehensile forehead,” I say.

“Did she?” Mum says, frowning.

“Yes,” I say.

“I suppose you’re going to go putting that into an Awful Book,” Mum says.

“Well?” I persist.

“Oh, I suppose,” Mum admits reluctantly. “Yes, there was a bit of a problem so none of the girls wanted to go out with him and that led to much more serious problems.”

“Like what?” I ask.

Mum gives me a look. “Just more serious problems,” she says darkly.

MUM WAS NEARLY SIXTEEN BY the time the Mau Mau uprising had been quelled in January 1960. Fewer than a hundred Europeans had been killed. Official British sources estimated that British troops and Mau Mau rebels had killed more than eleven thousand black Kenyans, but in a 2007 article in

African Affairs,

the demographer John Blacker estimated the total number of black Kenyan deaths at fifty thousand, half of whom were children under ten. The insurgency had been quashed, but news of atrocities British soldiers and white settlers had committed made headlines in Britain and the British lost their stomach for the colony. “Independence was inevitable,” Mum says.

In preparation for self-rule in Kenya, African leaders pressed for the resettlement of those Kikuyu who had been incarcerated in the labor and concentration camps during the Mau Mau. In July 1960, government officials arrived on the Huntingfords’ farm and begged my grandparents to take in a Kikuyu family. My grandfather looked out at his little farm, with its freshly planted windbreaks and carefully contoured lands. “I don’t see why not,” he said.

Duly, the Njoge family set up their homestead upwind of Martin Angleton’s little thatched shack. Martin traveled downwind to welcome them to the farm. “And the next thing you know people started teasing my father at the club, asking him if he had put up the banns.” Mum blinks at me, as if the astonishment of this moment has not yet worn off. “It turned out that Martin had gone and got himself engaged to Mary Njoge.” Mum narrows her eyes. “Well, the wedding went off without a hitch. Everyone brought a fish slice or whatever it was. And that was that—the new Kenya.” Mum pauses, “So you can say what you like, but we were all very progressive.” She has to search for the other word. “Yes,” she says at last, “

egalitarian

.”

IN 1961, THE YEAR SHE turned seventeen, it was decided something should be done with Mum. “My parents wanted me to learn how to be useful and that wasn’t going to happen as long as I stayed in Kenya.” They sent her to Mrs. Hoster’s College for Young Ladies in London and put her up in a women’s hostel in Queensgate. “I’ll never forget—as soon as you opened the door, there was this awful stench of overcooked cabbage,” Mum says. “Then I suppose they got extractor fans and blew it all up into the ozone and now it doesn’t smell so bad, but back then the whole of England reeked of boiled cabbage.”

Mrs. Hoster’s College for Young Ladies was a very reputable establishment opposite the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, “run by a bunch of scary, tweedy lesbians. Although some very noble people went there.” She shuts her eyes and counts them off on two fingers. “Prince Philip’s assistant went there, passionate about being posh. And the Dalai Lama’s sister—she went there too, passionate about the cause.”

Every morning, students at Mrs. Hoster’s College for Young Ladies were stationed behind Remington typewriters. “About two tons of steel, and they would put on records of military music and we were supposed to type in time to the Coldstream Band. Clickety-clack, clickety-clack.” Then Mum gives a rendition of herself typing. “On the other hand—pause, ping—pause, ping—pause, ping. That was my corner.” And in the afternoon shorthand practice. “Well, I could never read back what I had written—it just looked like a madwoman’s scrawl to me.”

Mum sighs. “It took me longer to complete the course than everyone else because I was not passionate about being a secretary. And I had chronic sinus problems.” She hesitates and then corrects herself. “Actually, not really. It was London in the sixties. There was so much going on. I didn’t have sinus problems at all, I had hangovers.”

“You were a hippie?” I ask.

“Hippie?” repeats Mum coldly. “Don’t be ridiculous, Bobo. No, these were the years of the Cold War; lots of lovely intrigue and hanky-panky—the Profumo affair, Mandy Rice-Davies, Christine Keeler. We all confidently expected that we were going to get blown to pieces by the Russians at any moment; it was terribly exciting.” Mum shakes her head, “And I wasn’t going to die learning bloody shorthand, that’s for sure.”

Catherine Angleton offered to hold a ball so that my mother could come out. “Not out of the closet,” Mum says, as if this is what I am about to suggest. “I was supposed to creep out from behind the typewriter to be formally presented to society. But I didn’t want to be a debutante. I didn’t see the point. Anyway, the sort of Englishmen who went to those balls would have sneered at me because I was a colonial.” She sighs. “They’d all have been terribly snobbish and listened like hawks for a slip in my accent; if I made the slightest mistake with my pronunciation, they would have pounced.”

YEARS LATER, MUM TRIED TO drill proper accents into Vanessa and me. Hours and hours of BBC radio were streamed into our ears in the hope that Received Pronunciation would rub off on us. And she did what she could to bring our voices down an octave or two—our high-pitched Rhodesian accents made us sound like adenoidal chipmunks. Auntie Glug thought we sounded sweet; Mum thought we sounded appalling.

My current accent is, according to Mum, appalling too—a hybrid Southern-African-English-American patois, barely recognizable as the language of Elizabeth II. My sister isn’t much better. She came home from the time she spent in London in her late teens and early twenties with what Mum calls “a dreadful cockney twang” to complement her colonial clip. “I can never tell if Vanessa is deliberately trying to wind me up,” Mum says, “or if she just does these things because she doesn’t care.”

When I ask Vanessa which of these it is, she takes a long drag off her cigarette and says, “Both.”

In addition to being bombarded by Received Pronunciation, Vanessa and I were instructed in a bewildering list of prohibitions regarding speech and vocabulary. It was vulgar to talk about money, which suited us because we seldom had any worth mentioning. (Money was also supposed to be frivolously frittered—when Mum finally came into a small inheritance upon her mother’s death in 1993, she spent it on books, horses, Royal Ascot hats and a protracted visit to London’s West End, where she saw every show playing.) It was also vulgar to talk about one’s health. “No one

really

wants to know how you are,” Mum said, “so just tell everyone you’re marvelous.” We had to say

napkin

instead of

serviette, loo

instead of

toilet, veranda

instead of

stoep, sofa

instead of

settee,

and

what?

instead of

pardon?

We were told it was rude to ask if someone wanted “

another

drink.” You always asked if they wanted “

a

drink” or “the other half.”

At school, however, the matrons gave us milk of magnesia for our bowels even when we told them we were “marvelous.” The teachers thought

what?

and

loo

were uncouth. They corrected Vanessa and me, and told us to say

pardon?

and

lavatory.

Meanwhile, half the students at our school thought being posh meant excessive primness and drinking their tea with a raised pinkie. The other half didn’t care at all about manners and cultivated a deliberate unposhness. I did my best to fit in.

“Well, it’s up to you,” Mum said. “But don’t blame me if you’re invited to tea with the Queen, and don’t have a clue how to behave.”

BY DECEMBER 1963, it was decided that all that could be done for Mum at Mrs. Hoster’s College for Young Ladies had been done. “After two whole years, I still couldn’t type and I couldn’t do shorthand.” Her eyes flame. “They tried to tame me and they failed.” A week later, Mum left London and landed in perfect, equatorially lit Nairobi. “I had my hair dyed blond and cut shoulder length, very sophisticated,” she says. “Those were the days when you dressed to the nines to fly and I wanted to look my best for Kenya.” She wore navy blue winklepickers and a pale blue linen suit. “Off the rack but it gave the impression of being very posh—short enough to be intriguing but not so short as to upset the horses.” Mum smiles. “And oh, I’ll never forget the first breath of Kenyan air when I stepped off that plane—so fresh, so fragrant. And the light was so perfect, such unpolluted clarity.” She gives me a look. “Lots of people have tried to write about it, you know, but hardly anyone can capture it. You had to be there. You had to see it for yourself.”

What Mum does not say is that by the time she came home from England, Kenya was an independent country. In May 1963, the Kenya African National Union won the country’s first general election. As news of the results were released, thousands of Kenyans ran through the rain-drenched streets of Nairobi cheering, “Uhuru! Uhuru!” Jomo Kenyatta, the seventy-three-year-old former secretary of the Kikuyu Central Association, addressed the nation, calling for tribal and racial differences to be buried in favor of national unity. “We are not to look to the past—racial bitterness, the denial of fundamental rights, the suppression of culture,” he said. “Let there be forgiveness.” On December 12, 1964, the Republic of Kenya was proclaimed, and Mzee Jomo Kenyatta became Kenya’s first president.

“Yes, well,” Mum says.

PART TWO

O wye en droewe land, alleen

Onder die groot suidesterre. . . .

Jy ken die pyn en eensaam lye

van onbewuste enkelinge,

die verre sterwe op die veld,

die klein begrafenis. . . .

Oh wide and sad land, alone

Under the great southern stars....

You know the pain and lonely suffering

of ignorant individuals,

the remote death in the veld,

the little funeral. . . .

—DIE DIEPER REG. ’N SPEL VAN DIE OORDEEL OOR

’N VOLK, N.P. VAN WYK LOUW

Tim Fuller of No Fixed Abode

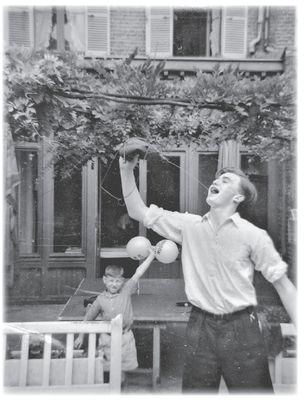

Dad. Paris, 1958.

D

ad is an upholder of the stiff-upper-lip adage: “If you don’t have anything nice to say about somebody, then don’t say anything at all.” Consequently, he is almost completely silent on the subject of his family. To be fair, his family have been equally silent on their own behalf and conspicuous for their almost total absence from our lives. Although, with our congenitally bad plumbing, land mines on the roads, snakes in the pantry and so on, it’s hard to blame Dad’s relatives for their lack of interest in coming to visit us.

Occasionally a relentlessly cheerful letter would arrive from England from Dad’s younger brother, Uncle Toe. And at Christmas, his wife, Auntie Helen, would sometimes send gifts of deliriously rare contraband (makeup for Vanessa and me, Irish linen tea cloths for Mum). But these infrequent communications seemed only to emphasize the enormous divide between the Fullers (us) who were sweating away in southern Africa and the Fullers (them) who we imagined were pinkly middling it out in Yorkshire or London or Oxford. And once or twice, at Mum’s insistence, we drove two hours west from the farm in the Burma Valley to visit the only relative of my father’s who had moved to Africa. “Cousin Zoo is blood family,” Mum told us firmly, “and blood”—she presented us with a fist—“Blood is blood.”

Zoo was terribly English and scrupulously if dutifully hospitable. She treated Vanessa and me as if we were visiting budgerigars that needed to be fed and then put somewhere dark for the night. And although Zoo seemed genuinely fond of Dad, it was chiefly his wasted eligibility that concerned her. “Your father was

terribly

good looking,

terribly

promising

,”

she would tell Vanessa and me. “He was our absolutely favorite cousin.” Accordingly, she arranged for my parents to sleep apart while under her roof: Mum in a spare bedroom, Dad locked in the workshop. It was as if Zoo hoped that a single night’s separation could erase or undo this inappropriately wild colonial marriage.

DAD HAD BEEN IN KENYA ONLY two weeks when he happened to be at the airport in Nairobi to meet the flight from England. “I suppose I was there to pick up someone, I can’t remember who,” Dad says. “All I remember is seeing this blonde get off the airplane in a pale blue outfit.” It was, of course, Mum, fresh from Mrs. Hoster’s College for Young Ladies. “Whew, you can’t imagine what your mother looked like, Bobo. Even from a distance, she knocked the wind out of a chap.” He leans over now and pats her hand. “Do you come here often or only in the mating season?” he asks. (It’s one of Dad’s old gags, borrowed from the BBC

Goon Show,

but Mum lights up as if it’s the first time she’s heard it.)

For her part, Mum was swayed by Dad’s baggy, knee-length Bermuda shorts. “Everyone else was in these horrible, tight little schoolboy boxer shorts with the pockets hanging out the bottom,” she says. So when Dad asked her to marry him, less than a month after they met, Mum said yes. Dad telegraphed England with the news of his engagement and the answer came back from his father, “Is she black? Stop. Don’t do it. Stop.” But my parents went ahead with their plans anyway. They were married in Eldoret on July 11, 1964. Photographs of that day are overwhelmingly (indeed solely) lopsided in favor of the bride: my grandfather is caught guffawing over a glass of champagne, my grandmother looks oppressed by the formal arrangement of flowers on her hat, Auntie Glug bursts out of her bridesmaid’s dress, Mum’s friends look drunk (in an outdoorsy, wholesome

pukka

-pukka sahib way).

No one from Dad’s side of the family came to the wedding, and their absence is the beginning edge of everything that followed. Mum is completely flanked but Dad is unsupported and what this will do to him is evident, the way his eyes already register a kind of wary separation from the rest of the world. Even with Mum by his side in each of these wedding photographs—maybe especially with her by his side (she overflowing with serene confidence, he with a monumental hangover)—Dad seems profoundly alone.

Perhaps because of this uneven beginning, we are defined less by my father than by my mother’s culture, people and family. Mum is African in her orientation, so we think of ourselves as African. She believes herself to be a million percent Highland Scottish in her blood, so we think of ourselves as springing onto African soil from somewhere wild and English-hating. My siblings and I are more than half English but this is hardly ever acknowledged. Even Hodge’s lengthy Anglican heritage (all those Church of England Bishops and vicars) is a footnote after the fact that he signed up to fight in the Second World War as “Scotch.”

And although my father is profoundly English, by the time I am old enough to know anything about him, he is already fighting in an African war and his Englishness has been subdued by more than a decade on this uncompromising continent. In this way, the English part of our identity registers as a void, something lacking that manifests in inherited, stereotypical characteristics: an allergy to sentimentality, a casual ease with profanity, a horror of bad manners, a deep mistrust of humorlessness. It is my need to add layers and context to the outline of this sketchy Englishness that persuades me to ask my reticent father about himself: I am searching for the time before he was alone, for the time when he was part of a tribe and a place. I am looking for the person he was before he became the man who would never ask for help, even if not doing so meant our lives.

IF MUM’S CHILDHOOD was set in a happily cramped, converted World War II officers’ barracks under perfect equatorial light on the wind-blown gold of the Uasin Gishu plateau, the majority of Dad’s childhood was set in Hawkley Place, a coldly large Victorian house in Liss, fifty miles south of London. “I spent my whole life outside, watching the haying or trailing around after the cowman from next door,” Dad says. He opens his penknife and uses it to scrape out his pipe and absentmindedly checks the blade against his thumb. “So that was good fun,” he says.

Dad’s parents had spent the first years of their marriage stationed in China. “I think they might have been happy there,” Dad says uncertainly. But he can’t produce any proof or details because by the time he arrived on the scene, on March 9, 1940, in Northampton Hospital, England, any romance or affection that once may have existed between his parents had long since burned off.

“China,” Mum muses. “How wonderful! Where in China?” she asks, but before Dad can answer, Mum’s mind leaps to Doris Day. “Shanghai in the 1930s,” she says. “What do you think?” And then she starts singing about leaving for Shanghai and being allergic to rice. “Tra la la la la laaaaa!” she finishes when she runs out of words, which is pretty soon.

This is the second day of our South African holiday. Mum, Dad and I are sitting in the garden of a tranquil lodge in the Cederberg Mountains, drinking tea. In the background, Cape turtle doves are calling the day to a mournful close, “Work hard-er, work hard-er.” A flock of guinea fowl croon in the field in front of us. White egrets flock across the sky to their roost. The cliffs behind us are struck golden pink by the setting sun. But the rareness of this exceptional peace is made still more singular by the fact that Dad is sitting still and he is speaking.

“Most talk is just noise pollution,” he says. At home in Zambia, you can hear him stamping into the kitchen for his tea long before dawn, muttering a greeting to the dogs, lighting his pipe. He is usually out of the camp, pacing the length of the irrigation pipes, checking the height of the river long before the rest of us have managed our first cup of tea.

At lunchtime—when the farm’s staff takes an afternoon break and the land itself seems to exhale heat—Dad will retreat from the punishing sun and sit under the Tree of Forgetfulness with his

Farmers Weekly

or catch up with a month-old

London Telegraph

crossword puzzle, but the activity is less restful than it sounds. His pipe is constantly moving from mouth to ashtray, and then (tap-tap-tap) it is emptied, refilled, lit, extinguished, scraped out, refilled yet again and so on. Then at four o’clock, the lengthening shadows seem to act as an irresistible lure. He clamps his pipe between his teeth and strides out of camp, back into his bananas or around the boundary of the farm. In Dad’s ordinary day, there is no room for reminiscences.

DAD’S MOTHER, Ruth—“Boofy”—was the youngest of six Garrard daughters: Garrard, of the Crown Jewelers, the oldest jewelers in the world, by appointment to HRH, the Prince of Wales. “And being a Garrard, everyone supposed Boofy had inherited a lot of money,” Mum says. “Actually, her chief Garrard inheritance was thick ankles.” Mum looks complacently at her own slim, tanned legs. “Poor Boofy,” she says.

What nobody says, but all of us know, is that Boofy was a catastrophic drunk, a legacy from her spectaculary alcoholic grandmother who died after falling leglessly backward into the fireplace. It would be logical to suppose that this would have put Dad off drinkers for life. On the contrary, nothing short of drinking a bottle of gin before breakfast for a decade at a time will convince Dad that a person has a real problem with alcohol. Moreover, a hangover is almost the only ailment for which he is likely to consider offering a person a consoling aspirin. Heart attacks, diabetes, influenza and migraines he regards as purely psychological. But admit to the effects of a late night and Dad is uncharacteristically caring. “Bad luck,” he’ll say, doling out a couple of tablets, “it must have been something you ate.”

Dad’s father, Donald Hamilton Connell-Fuller, was a commodore in the British navy (the position doesn’t translate to civilian life, where he was relegated to the rank of captain). To the world Dad’s father presented a witty, charming and devastatingly handsome front. But, “No, not tolerant,” Mum says. “And he had cold blue eyes like a dead fish.” She puts down her teacup for a moment and gives me her best impression of a flayed haddock. “He was very ambitious and he had a very short temper.” Donald made captain in 1942, when he was just thirty-three years old, and commodore shortly after that, but he never did make admiral, or even rear admiral, and he was bitter about it. “It didn’t help that wives were supposed to be supportive in those days, and poor Boofy would show up at regimental dinners with a flask of gin in her handbag and had to be carried out feet first before the fish course was served,” Mum says.

Concerned and preoccupied with their own deep disappointments and thwarted ambitions, the Fullers didn’t do much with their two young sons. There were no books at bedtime or visits to the cinema, no evening walks and very few meals together. “Sometimes we would be allowed on the battleships, and that was exciting,” Dad says. “And once in a while, my father played golf with Toe and he shot rabbits with me. Plus, there was one summer he took us both on a caravanning holiday in Ireland.” Dad pauses. “A lonely beach and it rained every day.”

Even from the distance of so many years and with the whole beautiful, fierce continent of Africa between me and the sodden Irish beach, I can feel the gloomy failure of that holiday in the pit of my stomach. “Oh God, that’s awful,” I say.

“The English after the war,” Mum explains. “So unhappy. So gloomy. So much boiled cabbage.”

BY NOW IN OUR SECLUDED kloof in the Cederberg, the doves in the tree above our heads are wing clattering into their night’s sleep. A single baboon in the cliffs barks a warning and the warm world feels leopard watched. A breeze picks up in the meadow and blows the cereal scents of grass and old heat-struck earth toward us. On an ordinary evening, we would have moved inside—a central African’s reflex against malarial mosquitoes—but on this inimitable night, none of us stir, the way no one gets up and leaves between movements at a concert.

“Anyway,” Dad says, at last, “there was always Noo. She was very good, very kind.” And it does seem telling that the presence of a Norland nurse, Irene Stanland—“Noo”—is felt on the edge of every photograph I have ever seen of Dad’s childhood, her off-camera, sterilized hands hovering at the ready to pluck my uncertainly smiling dad and his younger brother back to the nursery, where they were expected to be Seen But Not Heard in the manner of Blackie.

Blackie was Noo’s passionately adored cat. Even in the ration years after the war, the cat ate a pound and a half of prime steak a week. When he eventually died of complications from obesity, Noo had a taxidermist in London stuff him in an upright, sitting position. So there he sat on her bedside table, flatteringly slimmer than he had been in life and commendably uncomplaining. “It’s just the way it was in those days,” Dad says. “You spent your whole life sitting bolt upright and you only spoke when spoken to.”

It was the earth—the ground beneath his feet—that was the chief joy of Dad’s childhood. Every Christmas, and for several weeks of the summer, Dad and Uncle Toe were shipped off to Douthwaite Estate in the Yorkshire Dales to stay with their grandparents, Admiral Sir Cyril and Lady Edith Fuller. “I can close my eyes,” Dad says, “and picture that whole estate perfectly. Five farms all put together, rolling hills. Lovely, deep loam. . . .” Dad rubs his fingers together, as if he can even now feel the peaty softness of that old land, “No, you don’t find soil like that every day.”