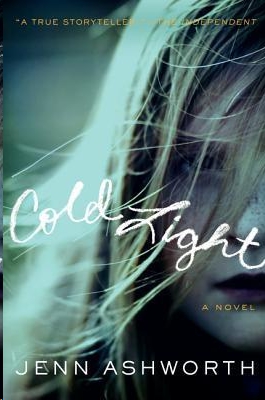

Cold Light

Authors: Jenn Ashworth

Cold Light

JENN ASHWORTH

Contents

Between interviews, they make us wait upstairs in a classroom. We’re left alone but we’re aware that in a nearby office we are being discussed. Teachers; her parents and mine; the nurse; social workers. And the pair of us with nothing to do but stare out of the windows at the bedlam occurring at the front of the school and wait.

We watch the cars arrive and unload. We lean on the sill, making palm prints in the dust. Emma rests her muscly thighs against the radiator. I pull leaves from a brown spider plant and we both look out of the window and say nothing. We listen. The glass muffles the crying and singing but we can still see the flowers and feel the atmosphere, which is shrieky and curious and raw.

These people who we don’t know – who Chloe doesn’t know – even turn up at the school in coaches. Every single one of them brings something. If it’s not roses and baskets of silk flowers then it’s stuffed bears and huge, handmade cards. So many ways of spelling her name.

They interview us alone, then together, then alone again. Because we’re only fourteen, we’re entitled to breaks. We don’t discuss the questions we’ve been asked. We don’t compare stories. I never know what Emma is going to say until she comes out and says it.

‘They’re putting candles out now,’ she says blandly.

She nods towards a kneeling figure across the road from the school. He is pulling something out of a carrier bag, laying it out on the pavement. A bank of tea-lights blooms as quick as mushrooms to drip and sputter in the shelter where the school buses pick up. Emma leans forward, putting all her weight on her hands. Her breath makes clouds on the glass. Her school jumper smells like old towels.

I stare at the flickering candles and remember the time me and Chloe waited there in the rain on a day we were supposed to be at school.

‘The wind’ll blow them out,’ I say. Emma nods and we wait, no one breaking the silence until Shanks comes back with another pair of police officers.

‘What is it now?’ I say, but not loud enough for Shanks to hear.

The police bring us cans of Coke and put their hands on our shoulders. Smile a lot, just to let us know that we aren’t in trouble and we shouldn’t be afraid of speaking out – of saying everything we knew about Chloe and her boyfriend. Sometimes they film us as we talk and make our parents sign pieces of paper afterwards to say it’s all right, that they don’t mind. I wonder if the cameras will be out this time, and what they’ll do with the recording, and if we’ll end up on the television again. Sometimes there are journalists waiting for us after school. They’ve promised to make special arrangements.

‘Right then,’ Shanks says, and I notice he’s taken the pack of fags out of his breast pocket, and that today he’s wearing a proper shirt and not a denim one.

‘They just want another five minutes with each of you, one at a time, and then you can go back to classes.’ He smiles, tries a joke, ‘No getting out of Maths today, I’m afraid, girls. Who’s first?’

Emma and I don’t look at each other. She steps forward. I see her ponytail bob from side to side against her neck. I don’t wonder what she is going to tell them. Shanks takes her away and I turn back to my window. Another coach has arrived.

They’re showing it this afternoon. A ceremony to mark the first spadeful of earth, and when it’s built, a ceremony to open the thing, I bet. I bring a bag of Doritos and a box of wine with me to the couch. Close the curtains, find the remote and settle in. The screen crackles with static as it warms up and I wonder, uneasily, what Emma is doing with herself tonight.

Beginning of this January, the council got together with the school and Chloe’s parents and set up a memorial fund. There was a consultation and a vote at a meeting in the Empire Services Club. The crowd was so big it overflowed the bar and spilled onto the bowling green. Someone came round with a tray of tea in those beige plastic cups with the plastic frame holders you get to stop you squeezing too hard and covering yourself in boiling liquid. We voted, all together, for a memory. A memorial. A house. The upshot of it is the City has decided to build a summerhouse overlooking the banks of her pond.

It’s not a pond and it’s not hers. It’s a concrete-bottomed pool, man-made and deeper than it looks. The yeast in the bread thrown to the ducks has polluted the water so there are no fish and no reeds – it’s a dead, black disc surrounded by a tangle of grey and leafless trees and hawthorn: their branches are decorated with torn carrier bags and faded crisp packets.

It’s not a place where anyone, least of all Chloe’s parents, would want to

sit and rest a while

, as it will say on the bench. But the City has decided. The council is putting up the money. Terry did the publicity and the telethon appeal for donations, and because the wood was the place were Chloe and Carl used to go – for their

privacy

– the summerhouse, decorated with stone doves and plaster cupids, surrounded by trellis and its own decking tracing a walkway down to the dirty banks of the pond, was what they planned.

They’ve built a model which the camera in the studio zooms in on so that on the television it looks like the real thing. This summerhouse (a concrete folly) is half a monument to young love gone wrong and half a nice piece of publicity for the City’s urban renewal programme: deprived areas, community cohesion – something for the teenagers to smoke their glue in. It’s morbid and sentimental, it ticks all the right boxes for community enterprise funding, and now it’s on

The City Today

.

This February has been wet and mild so the soil is easy to turn. The location camera shows the mayor attacking the cleared patch with a spade decked out like a maypole in pink and white ribbon. Chloe’s parents, because of their guilt, wanted the memorial to be a celebration of love and life and St Valentine and as a concession to this the City has provided the ribbons for the spade and the pink and white balloons –

gratis

. The mayor isn’t paying attention when he sinks the spade in but smiling at the pop of a few flashing cameras.

When the earth opens there’s nothing to see but some plastic – thicker than ordinary bin-bags, but nothing like tarpaulin. The blade of the spade tears open the plastic and a corner of it catches underneath. Even then, it’s nothing spectacular. Nothing, that is, we watching at home can

see

. No spectacle apart from a dirty fold of fabric that comes up with the soil as the mayor leans back and jiggles the spade so that the blade turns up the first clod. It could be anything – the cover from a pram, an old shower curtain, the material from an umbrella.

In fact, it’s a blue North Face jacket – waterproof and indestructible.

Terry peers into the hole, smiles, and then leans into the camera. The black bulb of the microphone is at his mouth. He says something, but I’m watching the weather girl who is standing next to him. She’s holding a white candle in one hand and a pink balloon in the other. They must have used helium – the string is straight up like a plumb line and the balloon floats over her head like an idea. Her smile freezes, then fades. Terry is still talking but the people behind him are screwing up their faces and coughing.

It’s the smell.

When the mayor heaves the spade backwards again, straining the row of buttons that bisects his belly, there’s an audible groan of disgust from the crowd and the weather girl lets go of her balloon, leans to the side and vomits a clear string of bile onto the ground. I watch the balloon float upwards, out of camera shot.

There’s chaos. The doves are flapping at the wire of the boxes they are stacked in. I don’t know if it’s because they can smell something too, or because the people around them are suddenly moving, jostling each other away from the little hole, talking too loudly. The camera doesn’t wobble, but pans away from the crowd, focuses on the still black water of the pond.

That’s what you get if you want to do these things live. Unforeseen events. Things are falling apart. Things have been falling apart long before the mayor cracked open the ground and unleashed a smell that had Terry’s weather girl vomiting into the bushes.

Terry apologises for the interruption and promises they’re getting a van out to the scene post haste but for the time being he’s going to have to hand back to the studio.

‘We will be back and when we are, we’ll tell you exactly what’s going on here,’ he says. He rakes a hand through his dishevelled hair, twitches his tie and hands back to Fiona, who is waiting on her couch, legs neatly crossed at the ankle and pressed together at the knee. She’s wearing an expensive camel-coloured two-piece suit with patent leather black shoes. Fiona wants Terry’s job. Beautiful.

‘That’s our Terry. Calm in a crisis, a consummate professional,’ she says, and the man practically bows. Fiona simpers. ‘First at the scene again. I think we’ll be in for a long one tonight, won’t we, Terry?’ The link is cut before he can reply and Fiona is left nodding at thin air and the programme’s logo on the screen behind her sofa.

‘We’ll be back,’ she says, ‘after this,’ and the adverts are as harried, jangling and garish as they usually are.

I let my eyes move to the window and sniff the air, which smells of crisps and fags, and the damp washing on the cold radiator. I don’t need to examine the screen. I can watch it again, whenever I like. It’ll be on YouTube before morning. I make a coffee, walk back to my couch slowly. There’ll be time to decide how I feel about this later.

Terry was totally cool – though that’s no surprise. He was in his element, because if Terry had an element it would be unexplained deaths, or euphemistically reported rapes. Fiona was right: he’s always first on the scene or the screen, bursting with bad news. She’s been hovering around, waiting for his job for years, but he’s the award winner. He’s the one we remember telling us about the pest that stalked the parks here ten years ago – the publicity and his campaign, even his tacit endorsement of the vigilante groups that sprang up, are supposed to have had more to do with the attacks ending than the efforts of the police, who could never give us a name. Not officially.

Terry Best. Famous for a cool head and a pink shirt. Various ties, often seasonal. But always, always the pink shirt. Sometimes his fans send him in different coloured shirts for Christmas and urge him to ring the changes, but he is never seen wearing anything but pink. He might only have one shirt, or five hundred that are all the same. Woolworths sell pink shirts and they did a special promotion for them in the window with a big poster of Terry. It didn’t say it in so many words but it strongly suggested that Terry Best bought his shirts from Woolworths. The management of

The City Today

complained and told them to take it down.

There’s a postcard you can buy in the bus station kiosk – him, with his thumbs up to the camera. The caption along the bottom, which is done in the same kind of glowing green writing as the

Twin Peaks

opening credits (although I don’t think many people will have noticed that) says: REAL MEN WEAR PINK. That’s never been banned, mainly because it isn’t advertising anything except for Terry himself.

Terry’s more of a fixture in some people’s lives than their families are because whatever happens, good or bad – he’s there. If you were expecting bad news, Terry would be the one you’d want to tell you. Most of the people who live in the City have a story about seeing him getting on a bus; complaining about the wait at the post office; carrying a rolled-up towel into the swimming baths. I’ve seen him once before myself, or at least I think it was him – suit jacket, pink shirt – hauling a heavylooking bin-bag from the back of his car, and dumping it on a verge by the side of the road. I mentioned it to my boss and she got breathless and asked me what was inside the bag. When I said I’d never checked, she refused to give me any overtime for a month.

He isn’t a regular at the shopping centre, but apparently he’s been in. Bobbed into Primark for two packets of navy blue socks. There’s a rumour that the manager wanted to give him the staff discount, messed up putting her card number into the till, and ended up just giving him the lot for free. She didn’t even ask for a signed picture to put near the revolving doors.

It is hard to explain to people who don’t live round here how important Terry is. Without ageing or changing his shirt, he has presented the local news bulletin every evening for twenty years which means he has been a part of most of the important things that have ever happened in this area. Every time the Ribble flooded. The time they tried to do a music festival in the park. That pub riot they had, and the ongoing debate about the multistorey car park on top of the bus station. He opens the new markets, welcomes in the Whitsun fair and turns on the Christmas lights every year. He presents the children’s book club certificates at the library, and he guest speaks at the AGM of the Real Ale Society.

I don’t expect the programme to return to its coverage of the memorial, but it does. Terry and his crew have shifted themselves, and sharpish. What started as jolly coverage of a foundation-laying ceremony quickly turns into breaking news and is piped into my room. The suddenly obscene decorated spade is hidden away; the mayor swaps his wellingtons for dress shoes, and Terry changes his tie. They reassemble in time for the police to arrive and erect their white tent over the place where the summerhouse was going to be.

This coverage will play all night. Chloe, upstaged at last. They haven’t named the body yet, but I know it is Wilson. I know.