Collected Essays (16 page)

Authors: Rudy Rucker

The hedonistic gnome didn’t quite have a brain-plug—but he was definitely plugged-in!

A lot of ideas in science fiction are symbols of archetypal human desires. Stories about time travel are often about memory and the longing to go back to the past. Telepathy is really an objective correlative for the fantasy of perfect communication. Travel to other planets is travel to exotic lands. Levitation is freedom from the shackles of ordinary life.

The brain plug is a symbol, first and foremost, for a truly effortless computer interface. Associated with this perfect user interface are notions of intelligence increase, technological expertise, and global connectedness.

In 1976, I wrote my first SF novel,

Spacetime Donuts

, which prominently features brain-plugs. In

Spacetime Donuts

, a brain plug is a socket in a person’s head; you plug a jack into your socket in order to connect your thoughts directly to a computer. The rush of information is too much for most people, but there is a small cadre of countercultural types who are able to withstand it.

When I wrote

Spacetime Donuts

, I was a computer-illiterate academic who taught and lectured about mathematics and philosophy. I feared and hated computers. I had no idea of how to control them. Yet at the same time I craved computers, I longed for access to the marvelous things they could do—the mad graphics, the arcane info access, the manipulation of servo-mechanisms. Thus the ambivalent fascination of the plug: on the positive side, a plug provides a short-circuit no-effort path into the computer; on the negative side, a plug might turn you into the computer’s slave.

Here’s what happens when my character Vernor Maxwell first plugs into the big central computer known as Phizwhiz.

“It was like suddenly having your brain become thousands of times larger. Our normal thoughts consist of association blocks woven together to form patterns which change as time goes on. When Vernor was plugged into Phizwhiz, the association blocks became larger, and the patterns more complex. He recalled, for instance, having thought fleetingly of his hand on the control switch. As soon as the concept

hand

formed in Vernor’s mind, Phizwhiz had internally displayed every scrap of information it had relating to the key-word

hand

. All the literary allusions to, all the physiological studies of, all the known uses for

hands

were simultaneously held in the Vernor-Phizwhiz joint consciousness. All this as well as images of all the paintings, photographs, X-rays, holograms, etc. of

hands

which were stored in the Phizwhiz’s memory bank. And this was just a part of one association block involved in one thought pattern.” [

Rudy Rucker, “Spacetime Donuts, Part I” (

Unearth

magazine, 1978.). The entire novel appeared from Ace Books.

]

I didn’t think of making up a word for the mental space inside Phizwhiz, and if I had, I probably would have called it a “mindscape,” meaning a landscape of information patterns, a platonic space of floating ideas.

The

Spacetime Donuts

mindscape is not very much like cyberspace. Why not? Because the mindscape comes all sealed up inside one centralized building full of metal boxes, a building belonging to the government—this was the old centralized, mainframe concept of computation. I didn’t ever think about bulletin boards, or modems, or the already existing global computer network. Although I understood about connecting to computers, I didn’t understand about computers connecting to each other in the abstract network that would become cyberspace.

In 1981, Vernor Vinge published a Net story called “True Names,” about a group of game-playing hackers who encounter sinister multinational forces in their shared Virtual Reality. Many view this story as the first depiction of cyberspace. And then William Gibson burst upon the scene with the stories collected in

Burning Chrome

, followed by his 1984 novel

Neuromancer

.

Rather than being modeled on the outdated paradigm of computers as separate individuals, Gibson’s machines were part of a fluid continuous whole; they were trusses holding up a global computerized information network with lots of people hooked into it at once.

Gibson usually describes his cyberspace in terms of someone flying through a landscape filled with colored 3-D geometric shapes, animated by patterns of light. This large red cube might be IBM’s data, that yellow cone is the CIA, and so on. Here, cyberspace is a great matrix with all the world’s computer data embedded in it, and it’s experienced graphically. But what about that brain-plug interface? Once you think about it very hard, it becomes clear that there really is no chance of having an actual brain plug anytime soon.

The problem is that our physiological understanding of the fine structure of the brain cells is incredibly rudimentary. And, seriously, can you imagine wanting to be the first one to use a brain plug designed by a team of hackers on a deadline? Every new program crashes the system dozens, scores, hundreds, thousands of times during product development. But—how would you reboot your body after some stray signal in a wire shuts down your thalamus or stops your heart?

In my novels

Freeware

and

Realware

, I tried to finesse the brain-plug issue by having a device I call an “uvvy.” Rather than being surgically wired into your brain-stem, the uvvy sits on your neck and interacts with your brain by electromagnetic fields. This futuristic technology is what the scientist Freeman Dyson calls “radioneurology.” He proposes that:

Radioneurology might take advantage of electric and magnetic organs that already exist in many species of eels, fish, birds, and magnetotactic bacteria. In order to implant an array of tiny transmitters into a brain, genetic engineering of existing biological structures might be an easier route than microsurgery.…When we know how to put into a brain transmitters translating neural processes into radio signals, we shall also know how to insert receivers translating radio signals back into neural processes. Radiotelepathy is the technology of transferring information directly from brain to brain using radio transmitters and receivers in combination. [Freeman Dyson, Imagined Worlds, (Harvard University Press).]

Speaking of “radiotelepathy,” I’ve unearthed an earlier use of the word, although not in exactly the same sense that Dyson uses it. This information isn’t totally relevant, but I’ll include it anyway. After all, we’re here to

Seek!

The passage in question occurs in one of my favorite books,

The Yage Letters

, where Allen Ginsberg is writing his friend William Burroughs a letter about a fairly nightmarish drug-trip he’d just had after taking a Curandero’s (a Curandero is one who “Cures”) mixture of Ayahuasca and other jungle plants in Pucallpa, Peru, in June, 1960.

I felt faced by Death, my skull in my beard on pallet on porch rolling back and forth and settling finally as if in reproduction of the last physical move I make before settling into real death—got nauseous, rushed out and began vomiting, all covered with snakes, like a Snake Seraph, colored serpents in aureole all around my body, I felt like a snake vomiting out the universe—all around me in the trees the noise of these spectral animals the other drinkers vomiting (normal part of the Cure sessions) in the night in their awful solitude in the universe—[I felt] also as if everybody in the session in central radiotelepathic contact with the same problem—the Great Being within ourselves—and at that moment—vomiting still feeling like a Great lost Serpent-seraph vomiting in consciousness of the Transfiguration to come—with the Radiotelepathy sense of a Being whose presence I had not yet fully sensed—too Horrible for me, still—to accept the fact of total communication with say everyone an eternal seraph male and female at once—and me a lost soul seeking help—well slowly the intensity began to fade. [

William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg,

The Yage Letters

, City Lights Books

).]

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality represents a practical step that interface designers have taken to try and make for a more brain-plug-like connection to computers.

In 1968 Ivan Sutherland built a device which his colleagues at the University of Utah called The Sword of Damocles—it was an intimidatingly heavy pair of TV screens that hung down from the ceiling to be worn like glasses. What you saw was a topographic map of the U.S. that you could fly over and zoom in on. The map was simple wire-frame graphics: meshes of green lines. Two of the main essentials of Virtual Reality were already there: (1) graphical user immersion in a 3-D construct, and (2) user-adjustable viewpoint. Soon to come as the third and fourth essentials of Virtual Reality were: (3) user manipulation of virtual objects, and (4) multiple users in the same Virtual Reality.

By 1988, cyberpunk science fiction had become quite popular, and the word “cyberspace” was familiar to lots of people. John Walker, then the chairman at Autodesk, Inc., of Sausalito, had the idea of starting a program to create some new Virtual Reality software, and to call it “Cyberspace.” In fact Autodesk trademarked the word “Cyberspace” for their product, “The Cyberspace Developer’s Kit.” William Gibson was rather annoyed by this and reportedly said he was going to trademark “Eric Gullichsen,” this being the name of the first lead programmer on the Autodesk Cyberspace project. I was employed by Autodesk’s Advanced Technology Division at that time, and I helped write some demos for Autodesk Cyberspace.

Graphical user immersion was brought about by using a lot of hacking and a lot of tricks of three-dimensional graphics. The idea was to break a scene up into polygons and show the projected images of the polygons from whatever position the user wants. It’s not much extra work to make two slightly different projections, in this way you can get stereo images that are fed to “EyePhones.” The only available EyePhones in the late ‘80s were expensive devices made by Jaron Lanier’s company VPL.

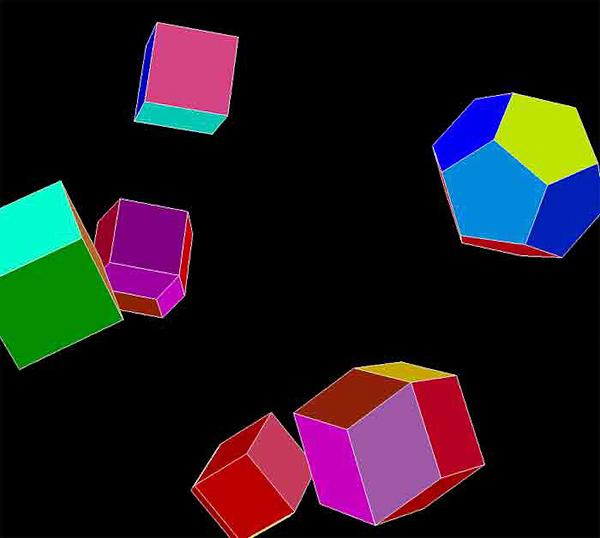

User manipulation was done by another of Lanier’s devices, the DataGlove. So as to correctly track the relative positions of their hands and heads, users wore a magnetic field device known as Polhemus. The EyePhones, DataGlove and Polhemus were all somewhat flaky and unreliable pieces of hardware, as were the experimental graphics accelerator cards that we had in our machines. It was really pretty rare that everything would be working at once. I programmed for over a year on a demo called “Flocking Topes” that showed polyhedra flocking around the user like a school of tropical fish, and I doubt if I got to spend more than five minutes fully immersed VR with my demo. But what a wonderful five minutes it was!

Polyhedra and tumbling hypercubes in cyberspace.

Supporting multiple users turned out to be a subtler programming issue than had been expected. When you have multiple users you have the problems of whose machine the VR simulation is living on, and of how to keep the worlds in synch.

In the end, the Autodesk product was a flop. It was too expensive and too constrictive. People were writing plenty of VR programs, but they didn’t want to be constrained to the particular set of tools that the Autodesk Cyberspace Developer’s Kit was supposed to provide.

One of the biggest growth areas for VR has been video games. Initially, home computers couldn’t support these computations, so one of the early forms of commercial cyberspace were expensive arcade games. One in particular was called “Virtuality”. Each player would get on a little platform, strap on head-goggles and gloves, and enter a Virtual Reality in which the players walked around in simulated bodies carrying pop-guns and trying to shoot each other. The last time I played this game was in a “Cybermind” arcade in San Francisco. I was by myself, scruffily dressed. My opponents were two ten-year-old boys with their parents. I whaled on them pretty good—they were new to the game. It was only after we finished that the parents realized their children had been off in cyberspace with that—unshaven chuckling man over there.

Of course now games like

Quake

and

Half-Life

show fairly convincing VR simulations on home computer screens. For whatever reason, head-mounted displays and glove interfaces still haven’t caught on. But the multiple-user aspect of VR has really taken off. There are any number of online VR environments in which large numbers of people enter the same world.

I just recently got a good enough computer to make it practical to visit some of these worlds. The online VR is amazing at first. You can run this way and that, looking at things. And there’s lots of other people in there with you, each in one of the body images known as “avatars.” Everyone’s talking by typing, and their sentences are scrolling past at the bottom of the screen.

What still seems to be missing from these worlds is any kind of indigenous life, although this may yet be on the way. As the writer Bruce Sterling once remarked to me about VR worlds, “I always want to get in there with a spray-can. It’s too clean.” It would be nice for instance to have plants, animals, molds, and the like. But for now, it’s the presence of the other people that makes these worlds compelling.