Color: A Natural History of the Palette (30 page)

Read Color: A Natural History of the Palette Online

Authors: Victoria Finlay

Tags: #History, #General, #Art, #Color Theory, #Crafts & Hobbies, #Nonfiction

When the king received the gift and looked at the portrait, he had an intuitive understanding of reality.

3

In terms of Buddhist teachings he realized that the world we see with our eyes is just a reflection of a reality that we cannot quite grasp. But the story also gives an insight into the power of painting, suggesting that this thing that is a reflection of truth can also somehow

be

truth, and that the best art can give its viewers enlightened understandings of the world.

As my train slowly rattled through the countryside, it was as if the land itself conspired to celebrate the myth that it was here that painting had begun: the whole landscape was covered with paint. It was harvest-time in Bihar, and the Hindu farmers celebrated the safe gathering of the crops by covering their animals in pigments. I saw a great cart moving toward the railway line. It was pulled by two white bullocks, both daubed in pink as if a child had been finger-painting over them. The paints I saw were synthetic, but there must have been similar scenes every harvest-time for hundreds of years. Perhaps it is what the Buddha saw, as he walked toward enlightenment; it is almost certainly what the Mughal rulers must have seen as they tried to conquer the predominantly Hindu sub-continent in the sixteenth century. And I am sure the British colonizers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw painted animals every September, celebrating the harvest.

I was not sure what to expect of Monghyr. My information was very out of date. In 1845 a Captain Sherwill, who had the job of revenue surveyor, described Monghyr as a town with “a probable population of 40,000 souls.”

4

It was, he wrote, “a well-built, substantial and flourishing place, with about 300 brick houses and numerous markets carrying on a brisk trade in brassware, cutlery of an inferior kind, guns, rifles, pistols and ironware in general, but of a very doubtful and dangerous nature as far as regards firearms.” I was intrigued by how, although Monghyr was clearly a welcoming place, the rest of the district was somehow shadowed by a kind of physical corruption that this British officer found threatening. The nearby town of Shaikpoora, he wrote with a horror that comes through even in his formal report to his bosses, was “remarkable for the great number of individuals who possess but one eye and have deformed noses, the effects of syphilis.” That town was “composed of one long narrow street of disgustingly dirty and ruinous houses, with a filthy population and very little trade; grain and sugar are exported toward the Ganges, and an opium godown is situated to the east of the town.”

There is a map that accompanies the statistics in Sherwill’s report. Monghyr and the nasty Shaikpoora are in pink, but the region of Bullah across the other side of the holy Ganges river is in a yellow that still shines. I like to think it was painted with Indian Yellow watercolor, even though when I sniffed it—making sure that my fellow library-users did not see what I was doing—I detected no faint 150-year-old scent of ammonia. Whether it was used on that map or not, Indian Yellow would almost certainly have been in the paintboxes of many of the surveyors and map-makers sent to the colonies in the Victorian years. Captain Sherwill’s report was extremely detailed about all the industries in the area—he even described a mysterious and obscure mineral found on a small hill, west of the station of Gya, “used for dyeing clothes, of an orange color, also for metalling the roads in the station. This mineral is either of an orange, purple, light-red or yellow color.” So it is extraordinary that he didn’t even mention Monghyr

piuri

.

Monghyr is a place that is entirely off the

Planet

—or any other guidebook—and I didn’t have any clues about where to stay. I told the taxi driver I wanted to go to a hotel, but he took me instead to an ashram, insisting this was where I wanted to go. Acolytes dressed variously in orange, yellow and white strolled quietly along empty avenues. It was a complete contrast to the noisy mayhem a few kilometers away in the town, but I could see that it wasn’t the place for me. White was for the uninitiated, I read in the brochure, aspirants wore yellow, and the teachers wore “geru.” “Can I ask a funny question?” I asked a slim young man with white stripes on his forehead, who was manning the office. “You can ask a funny question and I will give a fine answer,” he said. What is geru? “It is orange,” he said, indicating his own clothes which put him firmly in the highest category of Bihar yogis. “It represents the luminosity within.” And what does yellow represent? “Yellow is the light in nature. It invites the soul, as black protects the soul.” I nodded, and thanked him, but he had one thing more to tell me. “You see the thing about yellow is that it has to be purified.”

A friendly Bihar bank manager, fresh from a class, gave me and my bags a lift into town on the back of his scooter. “You have to go to see Monghyr’s oldest artist,” he said as I explained my quest above the sounds of the motor. “If anyone knows of this paint then Chaku Pandit at Mangal Bazaar will know.” So the next day I crossed the railway line heading toward Mangal Bazaar. Monghyr is a simple town—it reminded me very much of the India I saw eighteen years earlier on my first visit as a teenager. Everything is rickety, with places that were once probably palaces now hidden behind padlocked railings and being pulled down by vines and mold. The gun shops had gone, but there were plenty of hardware stores selling the kind of “inferior cutlery” that Captain Sherwill had commented on 150 years before. The syphilis problem was evidently still there as well: on every street corner there were hand-painted promises for venereal disease checks as well as operations for piles, conducted “without anesthetic.”

Everywhere the people seemed astonished to see me: they weren’t used to visitors. “Mangal Bazaar?” I asked, and the world followed me. “You go down the street and turn left,” an old man said, indicating right with his hand. You mean go right? I queried. “Yes,” he said, “left.” In the end neither was the correct way, but I did eventually find Chaku Pandit, a man with nearly blind blue eyes, in a blue house with round columns. We had a spontaneous conference organized by his son, with three of us on wooden chairs. One man went to get me a cold drink; another was summoned to sit on the floor and wave a punkah fan in my direction as the sweat ran down my nose onto my notes. “There are many kinds of

piuri

,” his friend said carefully. Which one was I interested in? I felt highly optimistic that I was on track to discover something. Mr. Mukharji, after all, had stated in his letter that there were two kinds of

piuri

—a mineral one “imported from London” and an animal one, which is what I was looking for. “Any kind,” I said airily, and a boy was sent off with careful instructions in Hindi. I tried to explain it was Krishna’s yellow, the one he always wears in watercolors, or at least the one he wears when he’s not wearing orange. They explained to me sadly that Krishna was blue; and it was in vain to protest that I knew this.

Chaku Pandit brought in a very brown Monarch-of-the-Glen-like portrait of a stag, the canvas bloated and bumpy where the damp had settled. His other paintings were rather gaudy pictures of idealized landscapes. The boy came back with a paintbox of oil tubes, manufactured in Bombay. “I have not heard of your Indian Yellow before. But why would we use cow urine when we have these good paints?” mused Chaku Pandit. I had to concede he was right, and thanking him for his time, his son for the cola and the man crouched on the floor for the fan, I went outside and hailed a cycle rickshaw. It had the motto “enjoyment of lovers” written on its seat. “Mirzapur, please,” I said. And we began to head out into the countryside.

I thought of Mr. Mukharji heading out on the same road 120 years before. What would he have been looking for? I wondered. Was he simply looking for a paint made by cowherds, or could there have been another reason for his interest? My predecessor had probably known that

piuri

had most likely been invented by the Persians in the late sixteenth century, and had mostly been used for miniatures—first by Mughal artists, later being adopted by the Hindus and the Jain painters. It was strange that the Jains—who are vegetarians and very strongly against inflicting pain on animals— should have painted with this apparently cruel color. “This is Mirzapur,” announced my driver, and stopped. It seemed we were not stopping anywhere in particular: it was a bit of road like every other bit of road. I was briefly encouraged to see a bovine creature peeing in a nearby meadow, but then realized it was a buffalo.

There was a little tea stall nearby, so I decided to do what I usually do when I’m hoping for an adventure. Sit, have a drink—tea in this case—and wait for it to come to me. I went over and the man made space for me to perch on the edge of a well. I hoped the tea water came from somewhere else, as the well water was covered in scum. Usually in this kind of situation someone will ask in English “What are you doing?,” leading me to my quest. But this time nobody did. Nobody could speak English. I cursed the fact that the young man I thought I had hired as my translator the night before had not turned up in the morning.

The stallholder was evidently a popular local character. He would leap up to put on the milk then go back to squatting on his wooden perch, carrying on conversations or handing a biscuit to a silent child. I was on to my second cup when I noticed his bare feet, and saw with surprise that this athletically built man had the worst case of elephantiasis I had ever seen on someone who was not a beggar. I asked him whether he knew of

piuri

but he just laughed nicely and asked me whether I knew of Hindi. I finished my tea and, wondering what the hell I was going to do without a translator and with a truly stupid and unlikely story about cow’s urine, stood up and crossed the main road. I headed down a path, and suddenly things began to happen.

Two boys appeared, returning from school, perhaps. “What are you doing?” they asked. “I’m looking for a

gwala

,” I answered, using the word for milkman that I had learned from Mr. Mukharji’s letter. The only people—perhaps in the world, certainly in India—who made

piuri

at that time, he had written, were members of one sect of

gwalas

at Mirzapur. “My father is a

gwala

,” one of the boys said happily, and pointed to his home at the end of the path. There were three cows in the shed and one by the trough. They looked well fed and the father seemed friendly. I began to draw in my notebook. “Buffalo?” they asked, as I drew something that I was convinced was an archetypal cow. “No, cow,” I said firmly, and drew in what I hoped would look like udders, but realized too late that they were rather gender-ambiguous. By now the whole family had gathered to engage in art criticism. “Tail!” the father demanded enthusiastically, so I added a tail and he nodded approvingly, the udder fiasco forgotten. The mango was easy, then the mango leaves, and then . . . Well, that first time I was not courageous; I drew a little bucket that could have contained anything and then started pointing to the walls of a nearby house, which were conveniently yellow. The son tried to explain, but nobody had heard of any connection between cows and yellow walls. “Come now, come!” said the boys, impatient to show me off to the rest of the village. So we continued along the path with the younger one chanting “Where is

gwala

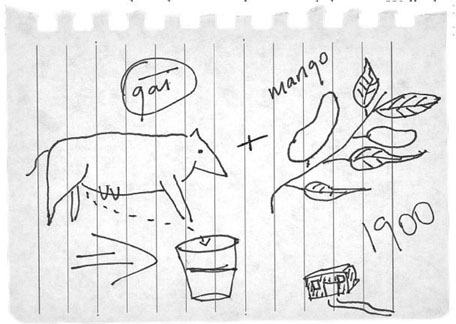

?” in great excitement.

A cow or a buffalo?

Mirzapur was not a rich place, but it was not devastatingly poor: people lived in simple houses with clean pathways and plenty of fields around. As we walked, other people joined us, and at the next home someone brought out a chair for me, and I was invited to tell my story again. I was just getting to the mango leaves, and the crowd had swollen to a hundred strong, when there was a sort of hush, and along the path came a charismatic young man with a most infectious smile. He was riding a tricycle that had been rigged up as a wheelchair. His knees were attached to the chair by small metal shields and he wheeled it with his arms, assisted by two friends. Here was another handsome young man of Mirzapur with a disability. He introduced himself as Rajiv Kumath; clearly he was a man to whom, when he spoke, people listened. So the cow thing started again, and the mango leaves, which was easy now because I knew the Hindi for leaf—but then came the moment of truth. Cow plus mango leaf plus . . . I drew a bucket then mimed squatting and made a ssssss-ing sound. “

Dudh?

” asked one boy, using the word for milk. “Er, no,” I said, and did the “sssss-ing” more enthusiastically. Looks of disbelief passed between the sari-wearing grandmothers and the younger women holding babies. Even the little urchins of Mirzapur could not believe that this smiling stranger could be quite so crude. Then, in the silence, there was a burst of clear laughter. Rajiv Kumath roared with joy and the whole village roared with him.

So, he summarized, “in 1900”—he pointed to the date I had written down—“people make yellow from this plus this plus this?” He indicated the pictures. “Yes,” I said. “Where?” he asked. “Here,” I said. “In Mirzapur.” He asked where else this happened. “Just in Mirzapur, nowhere else in India,” I said, and we spluttered with laughter at the absolute absurdity of it. “It’s called Monghyr

piuri

,” I added, “and it travelled from Mirzapur to Monghyr to Calcutta to England.” By this time both of us had tears running down our cheeks. Rajiv appealed to the crowd, but not even the old ones nodded in recognition of the practice. If

piuri

had ever been made in Monghyr it was not even a folk memory by the twenty-first century.