Color: A Natural History of the Palette (53 page)

Read Color: A Natural History of the Palette Online

Authors: Victoria Finlay

Tags: #History, #General, #Art, #Color Theory, #Crafts & Hobbies, #Nonfiction

I imagined the demigod striding out in his lion skin, worrying about the labors ahead of him, and absentmindedly throwing a stick across the pure white beach for his demidog to fetch. And then I imagined the animal bounding up a moment later, wagging its tail, with dye dripping from its teeth, and the master, astonished by this extraordinary color, carefully picking a specimen of

Murex brandaris

out of its mouth. It was a mythical discovery that would not only solve any short-term Phoenician financial problems but— given that every toga demanded the death of some ten thousand murexes—in the long term would put several species of sea creatures on the nearly-extinct list.

Some versions of the story add a female love interest in the form of the nymph Tyrus, who—on seeing what she felt was the beauty of the dog’s stained saliva—demanded that her boyfriend make her something equally beautiful, and so, as a Herculean labor of love, he obediently invented a special technique for dyeing silk. As if to illustrate the story I was imagining, a crowd of young Tyruses in tiny multicolored swimsuits suddenly rushed into the water and started giggling and splashing water over each other. A few meters away there were other young women swimming—but these were fully dressed, their headscarves and long-sleeved shirts drenched with salt water. They were also laughing and splashing, oblivious to the curious juxtaposition of two lifestyles on one beach. There is a story told locally of a U.S. army battalion storming the beaches in the 1980s, to rescue this Middle Eastern country from its tragic civil war. The Americans wore full battle gear as they rushed out of the water, but the only people there to witness their dangerous maneuvers were a few Lebanese ladies sunbathing in bikinis. It is hard to say which group was more surprised.

As I looked across the perfect sand to the almost perfectly still water, it was hard to believe that the sea was really too rough to go fishing. The Mediterranean is like that here, confirmed the man from whom I bought a soda. “It looks nice, but you have to be so careful.” I had to leave that afternoon. It seemed I had been so careful I had missed my murex.

A DYE FADES

On the way back to Beirut I stopped for a while in the Phoenician port of Sidon, just half an hour north of Tyre. The purple had been called Tyrian purple, but it could as well have been called Sidonian or Rhodesian (indeed, at one point in the Middle Ages there could have been an English bid for a Bristolian purple after a seventeenth-century traveller found purple-giving mollusks on that estuary and scholars confirmed something similar was used on old French, English and Irish illuminated manuscripts

19

). I wanted to investigate a curious landmark I had seen on the street map of the city. It was labelled “murex hill,” and it promised to be a mound of the mollusks that I had been looking for so unsuccessfully. I was hopeful of finding a broken shell or two to add to my growing collection of pigment souvenirs. It was mid-afternoon when I got there, and I drove round the tricky one-way system three times: up past the school, the apartment high-rises, the run-down cinema, and the locked Muslim cemetery, where I stopped and peered through the railings.

But to my dismay I found no sign of crumbling old shells or even any grassy Roman hillock. On the fourth circle I finally realized what was happening. The whole steep hill, with its roads and buildings and human headstones, was artificial, a gigantic grave-yard for millions—no, billions—of tiny creatures that died to allow Ancient Romans and Byzantine emperors to be born—and live and reign—“in the purple.” No wonder there were none left for me to find, I thought. They had used them all up.

Back in Beirut I reached the National Museum a few minutes before closing time. Once, not so long before, it had been at the very center of the line that divided the Christians from the Muslims in this troubled city. Most young Lebanese people had known it only as the place where the shelling started—until 1998 they had never seen the treasures that twenty-three years before had been hastily sealed in concrete where they stood, to protect them from the war.

There, dwarfed by the 3,300-year-old tomb of King Ahiram which holds some of the world’s first alphabetic writing, and overshadowed by the collections of Arab and Phoenician jewelry, was a small display case which held what I thought I was looking for. It was labelled “Tyrian purple,” but when I saw it I nearly choked with surprise. Because it wasn’t purple at all: it was a lovely shade of fuchsia. I suddenly wanted to smile. I had an image of Roman generals holding up their arms in triumph beneath suitably triumphal arches—clad from victorious head to victorious toe in pink.

Could this color, dyed onto a fluffy ball of unspun wool by a Lebanese industrialist called Joseph Doumet, really be the color of history and legend? The color I had been searching for? It is hard to know. Pliny mentioned several different murex colors, quoting another historian as saying “the violet purple which cost a hundred denarii a pound was in fashion in my youth, followed a little later by Tarentine red. Next came the Tyrian dye which could not be purchased for a thousand denarii a pound.” The latter was, Pliny commented, “most appreciated when it is the color of clotted blood, dark by reflected and brilliant by transmitted light.”

20

This, he suggested, was why Homer used the word for purple to describe blood. This pink wool in the National Museum—which I later discovered had involved tin as a mordant, to make the color stick— was not the color of clotted blood, or indeed of anything even vaguely like purple. It was very pretty, I decided, but it did not mark the end of my search.

In his book,

Color and Culture

John Gage finds the reasons for the purple cult of Rome and Byzantium “very difficult to define,”

21

but he does have an intriguing theory about it. The Greek words for purple seem to have had a double connotation of movement and of change. Perhaps this is accounted for by the many color changes involved in the dyeing process, but it is also, of course, the condition required for the perception of luster and of lustrousness itself. It is a theory borne out by Pliny’s description of clotted blood. And as I have found with so many of the most valuable colors I have gone looking for—especially sacred ochre in Australia, but also the best reds and the velvety blacks and, of course, that precious metal gold—one of the most important elements of their appeal is the way they have shone. It has somehow lifted a color or a substance from the level of secular to sacred—as if, by reflecting back some of the pure light of the universe, it embodies something holy. Or wholly powerful, at least.

As I flew back home the next day it was hard not to be disappointed. Even though this was the “home” of purple, it seemed that, apart from the little shred of experimental evidence at the museum, there was almost nothing of this color left in Lebanon at all. As I had seen so symbolically in Sidon, it seemed that murex had been subsumed into the historical structure of this ancient-modern country, while on the surface it was nowhere to be seen. But a few days later I cheered up on learning of another seashell purple which was perhaps even as ancient as the Mediterranean version but which, extraordinarily, seemed to have lasted right up until the end of the last century—and, if I was lucky, even to the present day.

THE PURPLE OF THE MIXTECS

In a description of their visit to Central America published in 1748, the Spanish brothers Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa described how the dyers of Nicoya in Costa Rica extracted purple from shellfish. There were two methods. The first method involved pressing the poor animal “with a small knife, squeezing the dye from its head into its posterior extremity, which is then cast off, the body being cast away.” The second method kept the creature alive. “They do not extract it entirely from its shell but squeeze it, making it vomit forth the dye. They then place it on the rock whence they took it and it recovers, and after a short time gives more humor, but not as much as at first.” However, the brothers reported, if the fishermen got over-enthusiastic and tried the same operation three or four times, “the quantity extracted is very small and the animal dies of exhaustion.”

The ancestors of these Costa Rican dyers were the famous pearlfishers of Queipo. Until about the seventeenth century they used to row to secret locations and then, clutching a heavy stone to their chests, they would sink down to depths of 25 meters or more to harvest their catch—holding their breath for at least three minutes. In 1522 Gil Gonzales de Davila, an emissary of the conquering King of Spain, visited the area, and found both pearls and purple, giving the area a double reputation for luxury. He brought back a dye sample of this

purpura

for the King, who gave it the grand brand name of New World Royal Purple, and, perhaps remembering the Roman precedent, demanded exclusive use.

In 1915 Zelia Nuttall, an archaeologist who was busy studying a series of ancient cartoon paintings made by the Mixtec people, made a visit to the Mexican seaside town of Tehuantepec. She was instantly struck by the purple skirts worn by some of the richer women in the marketplace, and, although she wasn’t a textile expert, wrote an article about what she had seen.

22

Most women wore hand-woven “turkey-red” skirts with narrow black or white stripes.

But the purple skirts that had attracted her attention were made of two widths of cotton, “united by a fine cross-stitching of orange or yellow,” which—a little patronizingly—she decided revealed a sophisticated understanding of complementary coloring. They cost ten dollars: three or four times the price of the other skirts.

The skirts particularly intrigued her because of the way they echoed some of the pictures she was studying. These were a series of pre-Columbian paintings on deerskin, containing coded information about the people and the gods depicted on them in a very two-dimensional way. The British artist John Constable famously disparaged them, but then, as fans of the codex reassured themselves, in the same speech (which he gave to the Academy of Art in London in 1833) he pronounced the Bayeux tapestry to be almost as bad.

At that time they were owned by an English aristocrat—Lord Zouche of Harynworth—but they are now known as the Nuttall Codex. What Nuttall noticed was how the

purpura

skirt color was identical to a beautiful purple paint she had seen on the codex, painted more than four hundred years earlier. One page “contains pictures of no fewer than 13 women of rank wearing purple skirts, and five with capes and jackets of the same color.” Even more striking, the codex also included pictures of eighteen people with their bodies painted purple: “in one case it is a prisoner who is thus depicted. In another a wholly purple person is offering a young ocelot to a conqueror, an interesting fact, considering that ocelot-skins were usually sent to the Aztec capital as tribute by the Pacific coast tribes.” And in another it was the high priest—shown twirling fire sticks and performing a sacred rite—who was wearing a closely fitting mauve cap.

One of the weavers in Tehuantepec showed Nuttall a basket full of twisted and dyed cotton thread that had just been brought on mule-back from a town farther along the coast. “Lifting one of the thick skeins, [the weaver] slipped it over her brown left wrist, and proceeded to show how she, as a child, had seen the fishermen at Huamelula obtain the dye from the

caracol

, or sea-snail.” Even by the time of Nuttall’s expedition the caracols had become so scarce that the fishermen were having to travel farther and farther away, even as far as Acapulco, to fulfill the orders. “Although Tehuantepec matrons still consider one of these somewhat in the light that our grandmothers regarded a black silk dress, as associated with social responsibility and position, fewer and fewer purple skirts are ordered every year, and the younger generation of women favor the imported and cheaper European stuffs,” she wrote. “Not more than about twenty purple garments were woven at Tehuantepec last year, and it is probable that before long the industry will be extinct.”

Her prediction, she would have been glad to discover, was premature. In the British Library I found a brief academic monograph

23

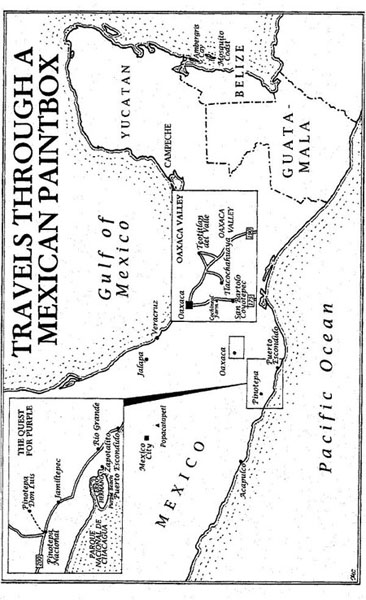

that described a successful Mexican dyeing expedition ten years before. So, armed with several photocopies of the article, I set off with a friend for the Pacific coast of Mexico, hoping I was not a decade too late to find the mysterious sea snails that weep purple tears.

Popocatepetl, the volcanic guardian of Mexico City, was spewing forth its red anger as we flew down to Puerto Escondido, making for a bumpy journey. The volcano-fuelled turbulence had the unwelcome side effect of tipping a smelly cargo of fish over my bag. I had come to find sea creatures, and it was, I thought pragmatically as I double-washed my luggage, perhaps a good augur for my search that they had already come to find me.

Puerto Escondido means “hidden port,” although in the past twenty years or so the place has been very much unhidden by the hordes of surfers and sun-seekers who descend every season, and evidently support whole families of T-shirt sellers. It is not a promising place to look for old traditions of any kind. A few boats go out to sea every night, arriving back at dawn for a fish auction on the sand, but most people there are outsiders, come to cash in on tourist dollars. A few locals had heard vaguely of the purple: Alfonso, a teacher of Spanish who we saw sitting open-shirted every morning at Carmen’s coffee shop looking for new customers among the tourists, said he had heard the snails were sometimes known as “margaritas.” My friend—a food writer who carried a compass to determine which location would be perfect for cocktails facing the sunset every evening—brightened visibly, but this was, apparently, nothing to do with salt around the edges of their shells. Alfonso wished us

mucha suerte

—good luck—in our search, and told us we’d need it. Later Gina at the tourist office reinforced the good-luck wish. “I think almost nobody does that dyeing anymore,” she said. But she told us to look out for two local characters called Juan and Lupe, describing them as “Puerto Escondido’s first surfers: still here, still hippies.” I would recognize them by their black Labrador retrievers, she said, and by their red-blue hair, colored apparently with Mexico’s natural sea dye. I imagined them as latter-day New World Hercules, walking their dogs along the beach and discovering purple. But during our two days in the town I didn’t spot them. They were probably sleeping, Gina said.