Colour Bar (51 page)

Authors: Susan Williams

The Botswana Democratic Party was returned to power in 1969 with an increased majority; then the party was re-elected in the 1974 elections and again in 1979. This meant that Seretse was under constant pressure as leader of the nation. Ruth did everything she possibly could to support him in his gruelling schedule, though she never interfered in his work. Her support became increasingly essential as his health deteriorated. She carefully monitored his diet and his daily routine, in a determined effort to maximize his strength.

39

But eventually, even Ruth could no longer keep Seretse alive. He became so ill that Ruth rushed him to London for specialist care, where he was diagnosed as suffering from the advanced stages of cancer of the abdomen. They were told that he would never recover. He and Ruth flew home so that he could take his last breath in Gaborone. There he died two weeks later at 4.45 in the morning of 13 July 1980. He was only 59 and had been president of Botswana for fourteen years.

The nation was numb with sorrow. A month of official mourning was declared, during which time flags flew at half-mast. Government held no official functions and the public were requested to keep private functions to small personal gatherings. Ketumile Masire, who succeeded as president, appealed to the people to face their loss with the dignity and calm that had been shown by their great President and to offer thanks: âMay God keep Sir Seretse Khama and we give thanks for the years we have been allowed to have him as our President.' Messages of condolence poured in from foreign Heads of State. âTo me, personally,' wrote President Kaunda of Zambia, âSir Seretse's death will mean the loss of a brother, wise counsellor and advisor. His steadying hand will be missed by all his brothers among the leaders of the Frontline States.' He was the kind of man, he added, who the strife-torn region of southern Africa could ill afford to lose.

40

One of his many achievements in the region was a leading role in negotiations to bring about the Independence of Zimbabwe under majority rule, which he witnessed just three months before he died. He also experienced another great joy before his death: in 1979, he saw the installation of his son, Seretse Khama Ian, who had trained

at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst in Britain, as Kgosi of the Bangwato people â Kgosi Khama IV.

The Memorial Service for Sir Seretse Khama was attended by 20,000 people and by many Heads of State, including Samora Machel of Mozambique, King Moshoeshoe II of Lesotho, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Dr Kaunda of Zambia, and the Reverend Canaan Banana of Zimbabwe. On the day after the service, Seretse was taken to the Khama burial ground in Serowe, at the top of the hill by the Kgotla, to be buried alongside the graves of the Great Khama III, his father Sekgoma II, and his uncle Tshekedi. All the way from the airstrip to the Kgotla, people lined the road, weeping, beside themselves with sorrow. The village was thronged by mourners and about twenty people fainted; women of all ages collapsed with grief and the atmosphere was melancholy. When the public were invited to see and pay their last respects to the late President, there was a stampede, causing some fractured limbs, because some people were afraid they would not get a chance to see him; as a result, the public were allowed to visit his coffin until six o'clock the following morning.

41

Seretse's death was announced by the BBC World Service, at the top of its news bulletin. Sir John Redcliffe-Maud, who had been the British High Commissioner of South Africa at the time of Independence, sadly lamented the loss in an obituary for

The Times

:

However dangerous the prospect, either for his country or his own health, his courage, integrity and tolerance were as steadfast as his sense of humour â but it was Ruth who kept him alive and happy. Africa owes both of them a great debt of gratitude.

42

Lady Khama was shattered.

43

She was now 56 and some people outside Botswana thought she would return to Britain. But the idea never crossed her mind:

I am completely happy here. I travel to Britain and Switzerland as part of my charity work for the Red Cross, but I have no desire to go anywhere else⦠My home is here. I have lived here for more than half my life. My children are here. When I came to this country I became a Motswana.

44

She lived alone on her farm in Ruretse, enjoying her children and grandchildren. She also continued to work hard for the Botswana

Red Cross Society, regularly attending the General Assembly at the international headquarters of the Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland. In 1982, Lady Khama became president of SOS Children's Villages, which was a project close to her heart. As Botswana started to suffer from the ravages of HIV/AIDS, making a growing number of children into orphans, she frequently visited the children at the SOS Children's Village in Tlokweng and did what she could to make them feel loved and cared for. She died twenty-two years after the loss of Seretse, at the age of 78, on 23 May 2002, on a night that saw the first rain in three months â even though it seldom rains in May. Her funeral in Serowe was attended by more than 10,000 mourners and she was buried in the hilltop cemetery reserved for the Khama family, next to her beloved husband.

Sir Seretse Khama has been internationally acknowledged as an outstanding statesman and one of the great successes of twentieth-century African politics. Whenever Nelson Mandela has saluted the heroes and giants of Africa, who ensured its liberation from the inhumanity of apartheid â such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Patrice Lumumba of Zaire, Amilcar Cabral of Guinea Bissau, Eduardo Mondlane and Samora Machel of Mozambique, W. E. B. Du Bois and Martin Luther King of the United States, Marcus Garvey of Jamaica, and Albert Luthuli and Oliver Tambo of South Africa â he has always included Seretse Khama of Botswana.

45

In 2000, he described him as âthat great son of Africa':

One of the great African patriots from this region, a man renowned for the manner in which he put the dignity and well-being of his people above all other considerations. The legacy of Sir Seretse Khama lives on in his country that continues to be a shining beacon of light and inspiration to the rest of us in Southern Africa.

âAs we stand at the beginning of a new millennium,' continued Mandela, âsincerely hoping that this will be the century of Africa and the developing world, the need to remain true to that legacy of Seretse Khama is as urgent as at any other time.'

46

âI think we were lucky,' observed Sir Ketumile Masire, who followed Sir Seretse Khama as President, âin that the combination of traditional

respect for Seretse and his personality really made him the ideal person to have started this country on the course in which it is going.' His marriage to Ruth, and all that went with it, added Sir Ketumile, âmade Seretse the Mandela of Botswana'. He had been close to both men, he added, âand it is remarkable how they were able to put the past behind them and act in exactly the opposite way in which a human being would usually act'.

47

Seretse simply did not have the capacity to hate. Even though Tshekedi had been so cruel to him, he forgave him totally. He never said anything against the people who had mistreated him and he never allowed cruel words from anyone else about them.

48

He could have been soured by his years of persecution by the British Government â but he was not. âI, myself,' he said in 1967 on a visit to Malawi, âhave never been very bitter at all, although at a certain stage I lived in exile, away from my country, in the United Kingdom for quite some time.' He went on:

Bitterness does not pay. Certain things have happened to all of us in the past and it is for us to forget those and to look to the future. It is not for our own benefit, but it is for the benefit of our children and children's children that we ourselves should put this world right.

49

1. Seretse Khama aged four, in Scottish Highland dress, at the installation of his uncle Tshekedi as Regent of the Bangwato, 1925. He is with Semane, Tshekedi's mother.

2. Law students in London, late 1940s: Seretse (right) with Charles Njonjo from Kenya, his old friend from their days at Fort Hare University, South Africa.

3. Tshekedi Khama leaving the offices of the British High Commissioner in Pretoria, 1949.

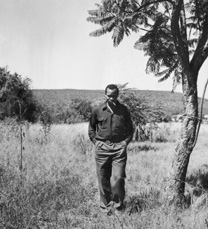

4. Seretse Khama in contemplative mood, Serowe 1950.

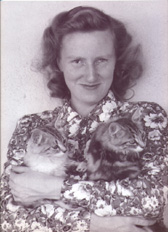

5. Ruth Khama in Serowe with her kittens, Pride and Prejudice, 1950.