Come as You Are (27 page)

Authors: Emily Nagoski

But most of us are just trying to live our lives as best we can. When it comes to investigating and understanding your own individual sexuality, you should cherry-pick. The moral views may be sincere, the media exciting, the doctors apparently expert, but you need not buy in to any system in order to create a coherent narrative of your own sexual self. You don’t need to believe you’ll go to hell if you have sex before marriage in order to decide whether waiting to have sex is a good choice for you. You don’t need to believe you’re sick or broken in order to wish you could just take a pill and want sex out of the blue. And you don’t need to believe that the key to great sex is flavored lube, a giant vibrator, and the ability to deep-throat in order to want to explore, try new toys, new tricks, and new partners.

And even though I’d love you to find meaning in every page, every paragraph of this book, cherry-pick from here, too. We’re all different, so what’s relevant for you is definitely, absolutely not the same as what’s relevant for me or for any of the many hundreds of women I’ve taught. Take what’s relevant. Ignore what isn’t; it’s there for somebody else who needs it.

Treat cultural messages about sex and your body like a salad bar. Take only the things that appeal to you and ignore the rest. We’ll all end up with a different collection of stuff on our plates, but that’s how it’s supposed to work.

It goes wrong only when you try to apply what you picked as right for your sexuality to someone else’s sexuality.

“She shouldn’t eat those beets; beets are disgusting.”

They might be disgusting to you, but maybe she likes beets. Some people do. And you never know, maybe one day you’ll try them and find you like them. Or not, that’s cool too. You do you.

“She shouldn’t have taken so many fried, breaded things—she’ll end up with a heart attack!”

She might and she might not, but either way it’s her heart and her choice. You do you. Absorb what feels right for you and shake off what feels wrong. Let everybody else do everybody else, absorbing what feels right for them and shaking off what feels wrong.

Laurie and Johnny’s story about “You’re beautiful,” sounds like a story about body image or disgust, but really it’s about love. Laurie’s body shame wasn’t just about the changes to her body. She had absorbed cultural beliefs about what those changes meant about her as a person. And because she believed her body was evidence that she was somehow a lesser person, she hid behind an emotional wall, so that no one could see those parts of her she felt ashamed of. But that wall also stood between her and the love she was starving for.

We build walls for a lot of reasons. To protect vulnerable parts of ourselves. To hide things we don’t want others to see. To keep people out. To keep ourselves in.

But a wall is a wall is a wall—it’s an indiscriminate barrier. If you hide behind a wall to protect yourself from the pain of rejection, then you also block out joy. If you never let others see the parts you want to hide, then they’ll never see the parts you want them to know.

When Laurie let the wall down, the love came flooding in.

No girl is born hating her body or feeling ashamed of her sexuality. You had to learn that. No girl is born worried that she’ll be judged if someone finds out what kind of sex she enjoys. You had to learn that, too. You have to learn, as well, that it is safe to be loved, safe to be your authentic self, safe to be sexual with another person, or even safe to be on your own.

Some women learn these things in their families of origin. But even if you learned destructive things, you can learn different things now. No matter what was planted in your garden, no matter how you’ve been tending it, you are the gardener. You didn’t get to choose your little plot of land—your SIS and SES and your body—and you didn’t get

to choose your family or your culture, but you do choose every single other thing. You get to decide what plants stay and what plants go, which plants get attention and love and which are ignored, pruned away to nothing, or dug out and thrown on the compost heap to rot. You get to choose.

• • •

In this second part of the book, I’ve described how context—your external circumstances and your internal state—influence your sexual wellbeing. I’ve talked about stress and love and body image and sexual disgust, and I’ve described some evidence-based strategies for managing all of these in ways that can maximize your sexual potential.

The next part of the book focuses on debunking some old and destructive myths about how sex works. These myths are part of the context in which women’s sexual wellbeing functions. In busting them, my goal is to empower you to take total control over your context and embrace your sexuality as it is, perfect and whole, right now. Even if you don’t quite believe that’s true yet.

tl;dr

• We all grew up hearing contradictory messages about sex, and so now many of us experience ambivalence about it. That’s normal. The more aware you are of those contradictory messages, the more choice you have about whether to believe them.

• Sometimes people resist letting go of self-criticism—“I suck!”—because it can feel like giving up hope that you could become a better person, but that’s the opposite of how it works. How it really works is that when you stop beating yourself up, you begin to heal, and then you grow like never before.

• For real: Your health is not predicted by your weight. You can be healthy—and

beautiful

—no matter your size. And when you enjoy living in your body today, and treat yourself with kindness and compassion, your sex life gets better.

• Sexual disgust hits the brakes. This response is learned, not innate, and can be unlearned. Begin to notice your “yuck” responses and ask yourself if those responses are making your sex life better or worse. Consider letting go of the yucks that are interfering with your sexual pleasure—see chapter 9 to learn how.

part 3

sex in action

six

arousal

LUBRICATION IS NOT CAUSATION

When you’re a sex educator, you get phone calls like this one:

“Hey, it’s Camilla. Can I ask you a sex question?”

“Sure.”

“You won’t be grossed out?”

“Of course not.”

“Okay, so Henry and I were messing around and I said, ‘I’m ready, I want you,’ and he said, ‘No, you’re not wet, you’re just humoring me.’ And I said, ‘No, I’m totally ready!’ And he didn’t believe me because I wasn’t wet. So . . . should I see a doctor? Is it hormonal? What’s wrong?”

“If you’re having pain you should see a doctor, but otherwise you’re probably fine. Sometimes bodies don’t respond with genital arousal in a way that matches mental experience. Tell him to pay attention to your words, not your fluids, and also buy some lube.”

“That’s it? Genital response doesn’t always match experience, so buy some lube?”

“Yep. It’s called nonconcordance.”

“But that’s not what . . . I mean, is this some new scientific discovery?”

“It’s kinda new. The earliest psychophysiological research I’ve read that explicitly measures sexual arousal nonconcordance is maybe thirty years old, though that—”

“Thirty years?

Why did no one tell me this before?”

This chapter answers that question, and a whole lot more.

The idea that genital response doesn’t necessarily match a person’s experience of arousal runs contrary to the “standard narrative” about sex. As far as most porn, romance novels, and even sex education texts are concerned, genital response and sexual arousal are one and the same.

For a long time, I thought the standard narrative was right—of course I did, I believed what I was taught. We all do. So I had no idea what to think when, in college back in the ’90s, a friend told me about her first experiences with power play in a sexual relationship:

“I let him tie my wrists above my head while I was standing up, and he positioned me so that I was straddling this bar that pressed against my vulva, you know, like a broomstick. And then he went away! He just left, and it was totally boring, and when he came back I was like, ‘I’m not into this.’ He looked at the bar and he looked at me and he said, ‘Then why are you wet?’ And I was so confused because I definitely wasn’t into it, but my body was definitely responding.”

Like everyone who has ever read a sexy romance novel, I was sure that wet equaled aroused. Desirous. Wanting it. “Ready” for sex. So what could it mean that my friend’s genitals were responding, when she really didn’t feel turned on or desirous at all?

What was going on?

Nonconcordance is what was going on.

In this chapter, I’ll describe the research on nonconcordance, including answering questions like, Who experiences nonconcordance? (Everyone, actually.) How do you know your partner is turned on, if you

can’t use their genitals as a gauge? (Pay better attention!) And how can you help your partner understand your nonconcordance? I’ll also address three wrong but beguiling myths about nonconcordance—and these myths aren’t just wrong, they’re

dangerously

wrong.

I want everyone who reads this chapter to go on a spree of telling the whole world about nonconcordance—that it’s normal, that everyone experiences it, and that you must pay attention to your partner’s

words

, rather than their genitals.

measuring and defining nonconcordance

Put on your sex researcher hat again and imagine conducting an experiment like this:

1

A guy comes to the lab. You lead him into a quiet room, sit him down in a comfortable chair, and leave him alone in front of a television. He straps a “strain gauge” (which is exactly what it sounds like) to his penis, puts a tray over his lap, and takes hold of a dial that he can tune up and down to register his arousal (“I feel a little aroused,” “I feel a lot aroused,” etc.). Then he starts watching a variety of porn segments. Some of it is romantic, some is violent, some features two men, some features two women, and some features a man and a woman. He rates his level of arousal on the dial as he watches, and the device on his penis measures his erection. Then you look at the data to see how much of a match there is between how aroused he felt—his “subjective arousal”—and how erect he got—his “genital response.”

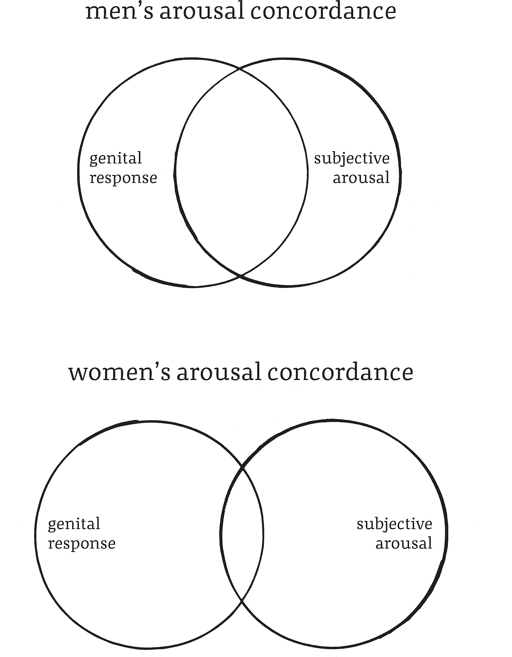

Result: There will be about a 50 percent overlap between his genital response and his subjective arousal. It’s far from a perfect one-to-one correlation, but in behavioral science it’s exciting to find a relationship that strong. It’s highly statistically significant.

For the most part, both our research subject and his penis will respond most to the porn that matches his sexual orientation: a gay man’s genitals respond most to porn featuring two men, and he’ll report the highest levels of arousal in response to it; a straight man’s genitals

respond most to porn featuring a man and a woman or else two women, and he’ll report the highest level of arousal in response to it, etc.

Now let’s run the same experiment with a woman. Put her in that quiet room, in that comfortable chair, and let her insert a vaginal photoplethysmograph (essentially a tiny flashlight that measures genital blood flow), and give her the tray and the dial and the variety of porn.

Result: There will be about a 10 percent overlap between what her genitals are doing and what she dials in as her arousal.

10 percent.

It turns out that there is no predictive relationship between how aroused she feels and how much her genitals respond—statistically insignificant. Her genital response will be about the same no matter what kind of porn she’s shown, and her genital response might match her sexual orientation . . . or it might not.

2

It’s called “arousal nonconcordance” and it’s totally a thing.

3

This research has been in the media a lot. For example, Meredith Chivers’s nonconcordance research was described in the

New York Times

and in a number of popular books recently.

4

Chivers’s work builds on the research of, among others, Ellen Laan, whose nonconcordance studies were also covered in the

New York Times

a decade earlier.

5

Chivers replicated Laan’s finding of greater arousal nonconcordance in women compared to men, with the innovation of showing research participants not only a variety of porn and nonsexual videos but also videos of nonhuman primates—bonobos, to be specific—copulating. It turns out women’s genitals respond to bonobo sex, too, though not as much as to porn.