Come August, Come Freedom (18 page)

Read Come August, Come Freedom Online

Authors: Gigi Amateau

HE MADE

it to the ocean. At Norfolk, Gabriel asked to go on deck; he wanted to look out at the sea.

Captain Taylor advised him otherwise. “Stay put for now. That ocean will be there when Quersey arrives. You best keep from the light of day.”

Gabriel stayed low; Taylor sent Billy into town to find the Frenchman. Quersey never showed.

The arrest happened quickly and without warning. Billy returned with two constables. The constables boarded the

Mary

and headed straight to Gabriel’s bunk. Captain Taylor hardly had time to concoct a story, and the one he offered convinced no one. “I — I was just belowdeck writing you a letter, Constable. To tell you of my prisoner.”

The Norfolk men arrested Captain Taylor, too. They shackled Gabriel at his ankles, with his hands bound behind him. Constable Obediah Gunn seized Gabriel’s papers — his letter from Quersey and another man from Philadelphia, the roll of names of soldiers from all across Virginia and into North Carolina, and the leaflet on which Nanny had written, for the first time, her name beside his. “Now it’s in writing,” she had said.

“Nanny and Gabriel.”

Billy stood on the dock, watching, ready to spend his reward.

The Lord, He throws no mercy my way. The business is done.

The men chained and ironed Gabriel, then took him before the mayor of Norfolk. He told nothing to his captors but said only, “I will speak to His Excellency, Governor Monroe. No one else.”

My only chance to see Nanny again is to get back to Richmond. If I am tried here in Norfolk, we have no chance.

When he returned to the capital, under guard, Gabriel found that a great crowd waited for him by the river. Some jeered and threw cabbages and squash. Others — Jacob, Mrs. Barnett, and the laundresses — walked with him up the hill to the governor’s mansion. The washerwomen sang, and their song lifted Gabriel up. They knew Gabriel, and they knew that his heart was at work not only for himself and Nan but for them, too. These women had showed him all about the creek and the river and taught him how to move about the city and hire out in his trade.

For these true companions, Gabriel felt grateful, but the one face he needed most he did not see. He searched the streets of Richmond for Nanny, and she was not among those at the river, along the hill, or on the capitol grounds.

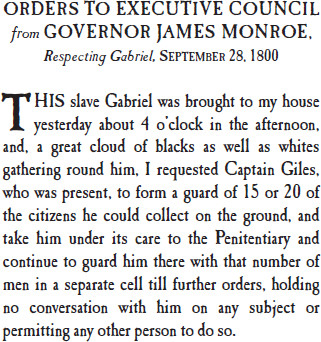

So massive was the crowd that the governor appeared on his porch, and upon seeing the gathering of black and white residents that had accompanied Gabriel, the terrified Monroe gave an order for fifteen or twenty men to surround Gabriel and remove him to the penitentiary.

From the crowd came cries to free Gabriel and shouts to hang him. The people asked for liberty, and they also asked for death. “Hang General Gabriel!” they cried. “Free the Black General!” they implored. The governor turned his back to all of the people and would not look at Gabriel.

“Inside the mansion, Governor Monroe’s young son is dying,” remarked one of the guards.

Ma’s Lord, He shows no mercy,

Gabriel thought.

September 24, 1800

Thomas Newton to the Governor

Norfolk

Excellency,

The bearers of this letter bring with them Negro Gabriel, taken from on board the three-masted schooner

Mary,

Richard Taylor, Captain, belonging to Richmond. It appears that Taylor left Richmond on Saturday night week and run aground on a bar 4 miles below Richmond.

On Sunday morning, Gabriel hailed the

Mary

and was brought on board by one of the Negroes on board. The villain was armed with a bayonet fixed on a stick, which he threw into the river. Captain Taylor says he was unwell and in his cabin when Gabriel was brought on board. Negro Billy says he was asleep, and when he awakened and found Gabriel on board, he questioned him. Gabriel said that his name was Daniel.

Capt. Taylor says that Gabriel came on board as a freeman, that he asked him for his papers but he did not shew any, saying he had left them; Capt. Taylor is an old inhabitant, been an overseer, & must have known that neither free blacks nor Slaves could travel in this Country without papers & he certainly must have had many oppertunities of securing Gabriel. In the eleven days Gabriel was on board the

Mary,

Captain Taylor passed Osborne’s Bermuda Hundred, City Point, and, I suppose, many vessels where he could have obtained force to have secured Gabriel. Taylor’s conduct after arriving here in Norfolk is also blamable.

Mary

was boarded by a Captain Inchman just below here, but Taylor never mentioned Gabriel. Even after he came up to town, he went alongside a ship with 25 men on board and never mentioned the matter.

When he was on shore, Negro Billy mentioned the matter to a boy by the name of Norris, a blacksmith. Norris told a Mr. Woodward, who immediately took such steps to send two constables on board the Schooner

Mary,

where they took him. Gabriel was at liberty on board and might have made his escape.

Mr. Taylor must have known & undoubtedly have heard of Gabriel before he left Richmond. I hope, for the sake of his family, Taylor may be able to clear himself of the opinion entertained of him here.

Gabriel says he will give your Excy. a full information, he will confess to no one else. He will set off this day under a guard, in a vessel & probably will reach Osborne’s by Friday or Saturday. Should Your Excy. think proper, a guard may be sent Down the River & take him by land, but they will proceed by water as fast as possible & I believe there will be no danger of a rescue.

I am with the greatest respect, Yr. Excy.’s Obt. Servt.,

Thos. Newton

Sheriff

NANNY WAITED

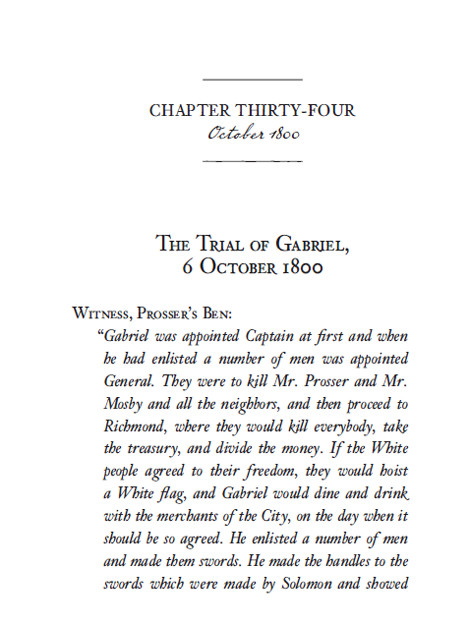

in the forest. On the morning Gabriel was set to hang, she arrived first to the woods behind Prosser’s Tavern, not far from Brookfield. Five men would die — Gabriel, Sam Byrd, George, Frank, and Gilbert. Word had quickly reached Henrico that Gabriel had petitioned the court to hang with his men in the countryside instead of alone at the gallows near the market house in Richmond.

Will they tie four ropes or five?

Nanny wondered.

Will I see Gabriel today, or will he die alone in Richmond?

The morning was clear and cool, the kind of autumn day that smells of a long-ago summer yet hints, too, at the long, suffering winter to come. The birds and rodents of the woods paid Nanny’s presence among them no mind but went about the business of foraging and burrowing and watching with her. The patrollers, assembling a makeshift gallows, paid Nanny no mind either.

She watched them to know if her husband would die alone.

Four ropes or five?

The sudden stillness of the child she carried or the empty quickening of the moment turned her queasy.

She found herself praying that Gabriel would hang there at Prosser’s Tavern and not in the city. She wanted to see him; she wanted to stand near him, sing to him, and sit by his body, caressing him until she was certain he had passed over.