Come Twilight (2 page)

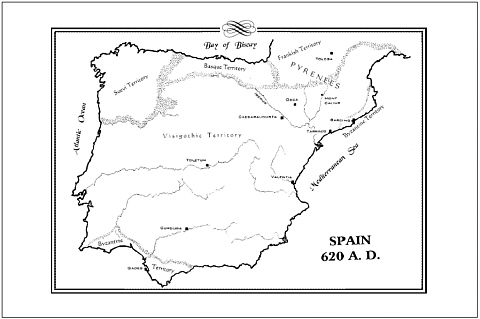

As always, there are thanks due to a number of people: to Father Joseph Avila for providing information on Visigoth Spain, particularly the role of the Gardingi; to Eleanor Westfield for access to her impressive library on the break-up of the Roman Empire; to Harold Pinkser, for the use of his maps and photographs of Catalonia, particularly his records regarding erosion and soil chemistry; to James Castion for material on the Moorish invasion of Spain; to Annemarie McNaughton for her expertise on the development of Spanish agriculture during the Moorish occupation; to A. G. for information on folklore traditions on sacred blood and Grail legends; to Philip Krasny for explaining the problems of deforestation in Catalonia during the Moorish occupation; to Pat Lee for the opportunity to read her thesis on the politics of the Christian resurgence of the twelfth century, particularly in regard to trade routes; to Shaneesia Chaney for her records on Islamic and Christian intermarriage during the Moorish occupation of Spain; to Dana Henniger for architectural information on the Moorish period in Spain; to J. Westfield for references on the development of Early Spanish and language “drift”; and to Wallace Bruchmeyer for sharing his expertise on Mediterranean economics during the height of Moorish power, and the vacuum following the Moorish withdrawal from Spain. Errors in fact or opinion are certainly not the fault of any of these good people.

Thanks are also due to Bryan Cholfin and Melissa Singer, my editors, and the other good people at Tor; to Lindig Harris, for the newsletter (

[email protected]

or P.O. Box 8905, Asheville, NC 28814); to Robin Dubner, my attorney, who protects the Count; to Eugene Smith, Carla Serrano, and Paul Shaw, who read the manuscript for accuracy; to Maureen Kelly and Sharon Russell (with an extra thanks or two for other reasons), who read it for fun; to Wiley Saichek, for keeping tabs on the Internet and on my publishers; to Tyrrell Morris, for keeping my machines working and set up and maintaining my Web site

(www.ChelseaQuinnYarbro.com)

; to those bookstores that continue to keep Saint-Germain on the shelves; and to my readers, for persevering in their support of these adventures.

Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Berkeley, California

May 1999

C

SIMENAE

T

ext of a letter from Bishop Luitegild of Toletum to Gardingio Theudis of Aqua Alba in Iberus and Exarch of Aeso.

To the most esteemed Gardingio Theudis, the blessing and ave of Episcus Luitegild of Toletum on this most sacred occasion of Advent, when all good Christians pray for the redemption of sin and the coming of Grace, for surely it will not be long before the Son of God comes again to raise up the righteous and cast down the mighty as Holy Scripture promises us.

This is to inform you that the bearer of this tomus is a man worthy of your good consideration, for he is of high rank and reputation, esteemed by noble, merchant, and clergy alike. Nothing ill is said of him by any who have dealt with him. All praise his conduct. He enjoys the highest positions available to foreigners in Toletum, and we view his departure as a misfortune that will give us cause to lament his absence for many years to come.

It is his departure that prompts me to write to you, for you have immediate contact with Caesaraugusta, which is across the river from you. As the Gardingio of the eastern side of the river, it is in your power to speed or hinder the departure of this man and his servant when they present themselves at your fortress. You would be doing a Christian service to ease this man’s passage through your territory; I would re

member your kindness in my prayers for a full year, and I would intercede with the local authorities here in Toletum to the benefit of those in your region who remain obdurate in the Aryan heresy or in clinging to the pagan ways of the past. Surely such concessions will move you from your usual adamantine posture in these matters.

The man of whom I speak is one it would behoove you to receive well, with the courtesy due one who has been a companion to those of highest positions in the world. He has traveled much and can instruct you in many things that will prove useful to you as well as entertaining. He is educated and erudite, with the comprehension of one who has journeyed widely. Let me encourage you to listen to him and benefit from his wisdom. He is also skilled at healing and may be induced to treat any suffering from injury or disease at your fortress. You would do your dependents a disservice not to avail yourself of his talents in this regard.

To facilitate this introduction, I will include a description of the man, so you will not be abused by an imposter: his name is Franciscus Sanct’ Germain. He is of high birth and carries the winged eclipse as a badge of degree. He is somewhat above middle height, sturdily built, his actions are decisive and energetic, his features are pleasing but a bit irregular, his hands and feet are small and well-made. You will be taken by his eyes, which are of a blue so very dark they appear black. His hair is fashionably cut in the Byzantine manner, has some curl to it, and is a dark-brown color shot with ruddiness when struck by light, and he is clean-shaven. His voice is mellifluous and he speaks eloquently, but with an accent that I have not heard in anyone but him. His manser vant is a thin man of middle years with sand-colored hair and pale-blue eyes; he answers to the name of Rogerian.

While he has lived here in Toletum, he has gained high regard for his skill as a jeweler and goldsmith, and his devotion to civic works. He also has some skill with medicaments. In these capacities various he has earned the good opinion of the city’s Jews, who have praised his abilities and integrity in terms they usually reserve for their own; that does not mean he dealt only with Jews, for it is not so—he has been useful to everyone in Toletum, I would have to say. However, being a man given to study instead of contemplation, it is to the Jews that Sanct’ Germain is entrusting much of his property, including his house and a small villa outside the city walls, as he is bestowing his household goods upon the

poor of our faith, along with a donation to Sancta Virgine and the monastery Sacramentum.

I know that those Gardingi living away from Toletum, as you do, are not often minded to extend yourselves for those of us here, but I ask that in this instance you do as I have asked you to do. It will redound to your benefit in this life as well as in the life that is to come when God returns to judge all mankind; you will not want it said of you that you failed in your duty as a Gardingio and a Christian, as must surely be the case if you pay no heed to my bidding. You will not be the only Gardingio to whom I write, and if you decide to give no regard to my request, your peers will learn of it, and of the disgrace you have brought upon them.

Weather permitting, Sanct’ Germain should present himself to you before the Paschal Feast. He will be traveling with a small escort whose maintenance he will vouchsafe. It is my hope that you will extend your duty to providing him further introduction to those of your fellow Gardingi who control the roads to the east of you, so that Sanct’ Germain may continue his journey unimpeded. To that end, I am sending with this tomus my seal impressed on a writ of passage in the certainty that you and all other Gardingi will honor it in accordance with your vows of fealty.

May God give you good health, good fortune, and good fame. May you deserve and receive the confidence of your peers. May your children all live to hardy old age. May you never face a foe you cannot best. May your loins always be fruitful. May your fields and herds be bountiful. May you be spared the catastrophes of famine, flood, and war. May your women be faithful, chaste, and devoted. May your heirs be worthy of your accomplishments and uphold your dignity. May your name be remembered with awe. May your family be held in high honor from this time until God summons us to Judgment. Amen.

Episcus Luitegild

of Toletum and

the Seat of Sanctissimus Resurrexionem

Written and sealed on the first day of Advent in the 621

st

year of man’s

Salvation, in the calendar of Sanct’ Iago’s reckoning.

Darkness, like a malign shepherd, came striding out of the east, storm clouds dogging its heels. All of Toletum huddled down against the sides of the hills as if hiding from the approaching winter night; as the wind picked up a freezing mizzle settled over the city, promising snow before the night was much older. Drafts sniffled and moaned at the door and windows, while a leaching chill prowled the streets with a persistence that made many pray to Heaven to protect them from the insidious cold.

“When do you think this will let up?” asked Rogerian as he laid his hand on the shutters in the library. He looked more concerned than his master did; he was visibly fretting, which was unusual in a man of habitual composure.

“In a day or so, I hope,” Sanct’ Germain answered absently: he was standing over his athanor, waiting for the hive-shaped oven to cool enough to allow him to open its door. He was dressed in Byzantine fashion in a long-sleeved black silk paragaudion picked out with silver thread over narrow Persian leggings of knitted black wool. A thick-linked silver collar held his eclipse device, the workmanship his own.

“Then our departure will be delayed again,” Rogerian said. “I am sorry, my master.” He spoke in the Latin of his youth, a tongue that was now six hundred years out of date.

“No matter,” Sanct’ Germain said in the same archaic language. “The storm is a timely warning. I would just as soon winter here, safely indoors, than out on the road.”

“Not that we have not endured worse than storms,” said Rogerian with an attempt at humor.

“All the more reason to remain here for a while longer,” said Sanct’ Germain. “Our earlier experiences have shown us the folly of undertaking unnecessary hardships. And fortunately,” he added with a half-smile, “there is no pressing reason for us to leave, at least not yet. We have a few months before claims are made against us, or so the Episcus assures me.”

“I am sorry that I insisted we abide here for so long,” he said, his voice dropping to a near-whisper. “You tried to warn me, but . . .”

“I hoped you would not be disappointed,” Sanct’ Germain said, his dark eyes compassionate. “I know that I was when I made a similar attempt, long ago. You must not be surprised that you can find no trace of your descendants.”

“Yes.” Rogerian nodded his agreement, tugging at the sleeve of his old-fashioned dalmatica; he had augmented its warmth by adding a long tunica of boiled wool; both garments were mulberry-color, appropriate to a man of Rogerian’s position. “But winter is here, and that is a danger in itself. Those on the road may have the more obvious hazards, but a town has its own risks. But you seem worried about staying on here.”

“So I am.” Sanct’ Germain said calmly. “And I worry about the traveling, too. For many others than for us.” He glanced at the window. “Since it is necessary, I can arrange a delay.”

Rogerian looked startled. “With Episcus Luitegild’s safe conduct, shouldn’t we travel while—”

Sanct’ Germain chuckled. “We have no reason to think that he will withdraw his endorsement simply because we do not leave the moment it is handed to us. He is abrupt but not unreasonable. Who knows: waiting awhile before going might surprise the Praetorius enough to delay his claims; he could not declare me a fugitive if we do not leave at once. Episcus Luitegild may not have much power, but he could stop the Praetorius from seizing my property.” He studied the athanor a short while. “The Exarch might see it differently, of course.”

“You mean he might not accept an introduction delivered so long after it was issued? Do you think he would deny the Episcus the hospitality requested?” Rogerian was apprehensive. “Is there a good reason to suppose—”