Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (325 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

[She goes a step or two towards the right; then she stops,

returns, and carefully feels his pulse and touches his

face.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

[Softly and firmly.]

No. It is best so, John Borkman. Best for you.

[She spreads the cloak closer around him, and sinks down in

the snow in front of the bench. A short silence.

[MRS. BORKMAN, wrapped in a mantle, comes through the wood

on the right. THE MAID goes before her carrying a lantern.

THE MAID.

[Throwing the light upon the snow.]

Yes, yes, ma’am, here are their tracks.

MRS. BORKMAN.

[Peering around.]

Yes, here they are! They are sitting there on the bench.

[Calls.]

Ella!

ELLA RENTHEIM.

[Rising.]

Are you looking for us?

MRS. BORKMAN.

[Sternly.]

Yes, you see I have to.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

[Pointing.]

Look, there he lies, Gunhild.

MRS. BORKMAN.

Sleeping?

ELLA RENTHEIM.

A long, deep sleep, I think.

MRS. BORKMAN.

[With an outburst.]

Ella!

[Controls herself and asks in a low voice.]

Did he do it — of his own accord?

ELLA RENTHEIM.

No.

MRS. BORKMAN.

[Relieved.]

Not by his own hand then?

ELLA RENTHEIM.

No. It was an ice-cold metal hand that gripped him by the heart.

MRS. BORKMAN.

[To THE MAID.]

Go for help. Get the men to come up from the farm.

THE MAID.

Yes, I will, ma’am.

[To herself.]

Lord save us!

[She goes out through the wood to the right.

MRS. BORKMAN.

[Standing behind the bench.]

So the night air has killed him ——

ELLA RENTHEIM.

So it appears.

MRS. BORKMAN.

—— strong man that he was.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

[Coming in front of the bench.]

Will you not look at him,

Gunhild?

MRS. BORKMAN.

[With a gesture of repulsion.]

No, no, no.

[Lowering her voice.]

He was a miner’s son, John Gabriel Borkman. He could not live in the fresh air.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

It was rather the cold that killed him.

MRS. BORKMAN.

[Shakes her head.]

The cold, you say? The cold — that had killed him long ago.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

[Nodding to her.]

Yes — and changed us two into shadows.

MRS. BORKMAN.

You are right there.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

[With a painful smile.]

A dead man and two shadows — that is what the cold has made of us.

MRS. BORKMAN. Yes, the coldness of heart. — And now I think we two may hold out our hands to each other, Ella.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

I think we may, now.

MRS. BORKMAN.

We twin sisters — over him we have both loved.

ELLA RENTHEIM.

We two shadows — over the dead man.

[MRS. BORKMAN behind the bench, and ELLA RENTHEIM in front

of it, take each other’s hand.

FINIS

EN

A DRAMATIC EPILOGUE IN THREE ACTS.

Translated by William Archer

Ibsen’s last play was written in Christiania in 1899. There were many factors that distracted him from writing

When We Dead Awaken

. At the time he was involved in planning the first two collected editions of his works, including a German edition, published in nine volumes by the historians of literature Julius Elias and Paul Schlenther from 1898-1903, and the Norwegian edition, published by Danish Gyldendal in nine volumes from 1898 to 1900. Also, in the spring of 1898 Ibsen celebrated his seventieth birthday, with large-scale festivities held for him in Christiania, Copenhagen and Stockholm. He made speeches, gave interviews and received frequent visits in Christiania, further impeding the writing process of

When We Dead Awaken

until the beginning of 1899.

The title of the play was changed twice during the writing of the fair copy, first to ‘The Day of Resurrection’, then to ‘When The Dead Awaken’ and then finally to ‘When We Dead Awaken’. The fair copy of the manuscript was sent to the publisher the same day as it was completed, November 21, 1899. The full title of the play,

When We Dead Awaken. A Dramatic Epilogue in Three Acts

, was advertised before the book was for sale by the Danish newspaper

Politiken

, claiming that ‘epilogue’ signified that “the writer has spoken his last words in this play and has thus concluded his dramatic works”. Nevertheless, this claim was denied by Ibsen himself in an interview in the newspaper

Verdens Gang

on December 12, 1899.

When We Dead Awaken

was published by Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag on December 22nd

The first full staging of the play was at the Hoftheater in Stuttgart on January 26, 1900, followed shortly afterwards by productions in Copenhagen, Helsingfors, Christiania, Stockholm and Berlin. It proved difficult to make the play function satisfactorily on the stage, as Edvard Brandes wrote in connection with his production, “The actors were too small”.

The first act is set outside a spa overlooking a fjord, where we are introduced to the sculptor Arnold Rubek and his wife Maia, who are reading newspapers and drinking champagne. They marvel at how quiet the spa is. Their conversation is light-hearted, but Arnold hints at a general unhappiness with his life and Maia also hints at disappointment. Arnold had promised to take her to a mountaintop to see the whole world as it is, but they have never done so.

The hotel manager passes by with some guests and inquires if the Rubeks need anything. During their encounter, a mysterious woman dressed in white passes by, followed closely by a nun in black. Arnold is drawn to her for some reason. The manager does not know much about her, and he tries to excuse himself before Squire Ulfheim can spot him. Unable to do so, Ulfheim corners him and requests breakfast for his hunting dogs. Spotting the Rubeks, he introduces himself and mocks their plans to take a cruise, insisting that the water is too contaminated by other people. He is stopping at the spa on his way to a mountain hunt for bears, and he insists that the couple should join him, as the mountains are unpolluted by people.

The play is dominated by images of stone and petrification — the process by which organic material is converted into stone through the replacement of the original material. Ibsen’s final play is a despairing work, full of probing questions as to what it is to have truly lived a life and not to have wasted it.

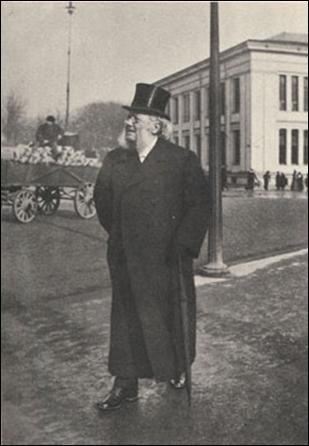

Ibsen, at the time of writing his last play, in Christiania, 1899

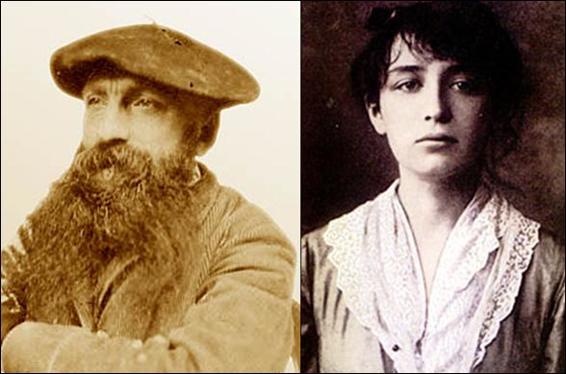

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) and his lover Camille Claudel. Some critics argue that the play is based on their relationship.

The Hardangervidda mountain plateau in central southern Norway is the setting of the last two acts.

From

Pillars of Society

to

John Gabriel Borkman

, Ibsen’s plays had followed each other at regular intervals of two years, save when his indignation over the abuse heaped upon

Ghosts

reduced to a single year the interval between that play and

An Enemy of the People

.

John Gabriel Borkman

having appeared in 1896, its successor was expected in 1898; but Christmas came and brought no rumour of a new play. In a man now over seventy, this breach of a long-established habit seemed ominous. The new National Theatre in Christiania was opened in September of the following year; and when I then met Ibsen (for the last time) he told me that he was actually at work on a new play, which he thought of calling a “Dramatic Epilogue.” “He wrote

When We Dead Awaken

,” says Dr. Elias, “with such labour and such passionate agitation, so spasmodically and so feverishly, that those around him were almost alarmed. He must get on with it, he must get on! He seemed to hear the beating of dark pinions over his head. He seemed to feel the grim Visitant, who had accompanied Alfred Allmers on the mountain paths, already standing behind him with uplifted hand. His relatives are firmly convinced that he knew quite clearly that this would be his last play, that he was to write no more. And soon the blow fell.”

When We Dead Awaken

was published very shortly before Christmas 1899. He had still a year of comparative health before him. We find him in March 1900, writing to Count Prozor: “I cannot say yet whether or not I shall write another drama; but if I continue to retain the vigour of body and mind which I at present enjoy, I do not imagine that I shall be able to keep permanently away from the old battlefields. However, if I were to make my appearance again, it would be with new weapons and in new armour.” Was he hinting at the desire, which he had long ago confessed to Professor Herford, that his last work should be a drama in verse? Whatever his dream, it was not to be realised. His last letter (defending his attitude of philosophic impartiality with regard to the South African war) is dated December 9, 1900. With the dawn of the new century, the curtain descended upon the mind of the great dramatic poet of the age which had passed away.

When We Dead Awaken

was acted during 1900 at most of the leading theatres in Scandinavia and Germany. In some German cities (notably in Frankfort on Main) it even attained a considerable number of representatives. I cannot learn, however, that it has anywhere held the stage. It was produced in London, by the State Society, at the Imperial Theatre, on January 25 and 26, 1903. Mr. G. S. Titheradge played Rubek, Miss Henrietta Watson Irene, Miss Mabel Hackney Maia, and Mr. Laurence Irving Ulfheim. I find no record of any American performance.

In the above-mentioned letter to Count Prozor, Ibsen confirmed that critic’s conjecture that “the series which ends with the Epilogue really began with

The Master Builder

.” As the last confession, so to speak, of a great artist, the Epilogue will always be read with interest. It contains, moreover, many flashes of the old genius, many strokes of the old incommunicable magic. One may say with perfect sincerity that there is more fascination in the dregs of Ibsen’s mind than in the “first sprightly running” of more common-place talents. But to his sane admirers the interest of the play must always be melancholy, because it is purely pathological. To deny this is, in my opinion, to cast a slur over all the poet’s previous work, and in great measure to justify the criticisms of his most violent detractors. For

When We Dead Awaken

is very like the sort of play that haunted the “anti-Ibsenite” imagination in the year 1893 or thereabouts. It is a piece of self-caricature, a series of echoes from all the earlier plays, an exaggeration of manner to the pitch of mannerism. Moreover, in his treatment of his symbolic motives, Ibsen did exactly what he had hitherto, with perfect justice, plumed himself upon never doing: he sacrificed the surface reality to the underlying meaning. Take, for instance, the history of Rubek’s statue and its development into a group. In actual sculpture this development is a grotesque impossibility. In conceiving it we are deserting the domain of reality, and plunging into some fourth dimension where the properties of matter are other than those we know. This is an abandonment of the fundamental principle which Ibsen over and over again emphatically expressed — namely, that any symbolism his work might be found to contain was entirely incidental, and subordinate to the truth and consistency of his picture of life. Even when he dallied with the supernatural, as in

The Master Builder

and

Little Eyolf

, he was always careful, as I have tried to show, not to overstep decisively the boundaries of the natural. Here, on the other hand, without any suggestion of the supernatural, we are confronted with the wholly impossible, the inconceivable. How remote is this alike from his principles of art and from the consistent, unvarying practice of his better years! So great is the chasm between

John Gabriel Borkman

and

When We Dead Awaken

that one could almost suppose his mental breakdown to have preceded instead of followed the writing of the latter play. Certainly it is one of the premonitions of the coming end. It is Ibsen’s

Count Robert of Paris

. To pretend to rank it with his masterpieces is to show a very imperfect sense of the nature of their mastery.