Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (2225 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

The work in question is an autobiography, and the writer of it is Mr. Edward Fitzball. To the younger generation of readers, this gentleman’s name may, not improbably, recal the remembrance of much conventional, jesting of the periodical sort, which never had a large infusion of the Attic salt of wit to recommend it; and which, in course of time, became intolerably wearisome to all but the jesters themselves, by dint of perpetual repetition. To us, it has always appeared a little unjust towards Mr. Fitzball to have mischievously paved the way, in his case, for the passage of ridicule, by representing him as filled to overflowing with literary pretensions, to which judging by his own words, in his own book, now under review he has never made any claim. As we understand it having no personal knowledge of Mr. Fitzball, and no object in writing, but the desire to treat him with all fair consideration he has never pretended to anything more than the possession of a natural dramatic instinct in the shaping of plots, and the placing of situations, and the acquisition of considerable experience in studying the tastes of the public of his time, as well as of great facility in making that experience tell for what it was fairly worth on the stage. He has claimed to have done this successfully, and the record of facts in his autobiography fairly establishes his claim. It may be an excellent joke against Mr. Fitzball that he has written plays which have run, in more cases than one, for two hundred nights, and have put thousands of pounds into the pockets of the managers but we are not sharp enough to see it ourselves. When a man starts as a dramatist, he fails, no matter what his style as a writer may be, if he empties the theatre; and he succeeds, no matter what his style as a writer may be, if he fills it, whether it be a large theatre, or a small one, a theatre on this side of the Thames, or a theatre on the other side of the Thames, whether he be a Syncretic whose tragedy in the blankest possible verse no human being has ever yet read, or whether he be Mr. Fitzball, whose melodramas, in the plainest possible prose, thousands and thousands of his countrymen have been glad to go and see. A man who can really accomplish what he has undertaken to do is such a rarity, especially on the English stage, that he deserves civil recognition at the very least. We are so inveterately comic now-a-days, that we must always laugh, even at the wrong man; and, in the mean, time, the quack who deserves our ridicule, too often escapes scot-free.

We find, from Fitzball’s autobiography, that his first attempt at stage composition was made on the boards of the Norwich Theatre. He there produced the Innkeeper of Abbeville, which succeeded well enough in the country to be reproduced at the Surrey Theatre, where it ran upwards of one hundred nights. His next attempts were Joan of Arc and The Floating Beacon, which were played together, nearly, if not more than four hundred consecutive nights. To our thin king this was not a bad beginning for a young man. Where are the dramatists, great or little, who begin, in that way, now?

As he gained in experience, he got on to wider successes. His Devil’s Elixir was a great hit, even with a critical Covent-Garden audience. His Pilot, Flying Dutchman, and Jonathan Bradford (this last melodrama running two hundred and sixty-four consecutive nights), were reported to have brought nearly twenty thousand pounds to the theatres in which they were produced. Besides writing these plays, he dramatised some of Scott’s and Bulwer’s novels; and, later in his career, he varied his exertions by writing the words (or by adapting them from foreign librettos) of some of the most popular operas that have ever appeared on the English stage. His poetry, taken by itself, was easy enough to ridicule, in these cases. But who, in the instances of other men, looks for fine poetry in opera-books? Who wants anything of an opera-book, but that it should be an easy and intelligible medium for conveying music to the public ear? If Mr. Fitzball accomplished this object, he did enough for the purpose for which he was employed. And, if he had written fine verses, who, of all the listeners to the music, would have found them out?

Excepting the cases of the operas, Mr. Fitzball’s adaptations from the French seem to have been commendably few in number. He took his plots from English stories, or from romantic events recorded in the newspapers. If a man cannot absolutely invent for himself, it is certainly more creditable to him as a dramatist, that he should take his materials from widely known national sources, than from foreign originals disguised to pass for English, and unacknowledged on the playbills. As no serial novels were published at that time, be anticipated no author’s stories, and committed no graver offence than that of attempting, generally with unmistakable success, to present the dramatic side of a popular novel, to an audience, for the most part, well acquainted with it already in its original narrative form.

We have indicated the outline of Mr. Fitzball’s dramatic career, as exhibited in his autobiography, and we may now leave the reader who is interested in the matter to refer to the work itself for all details, and for a plentiful supply of anecdotes in connection with the actors, managers, and dramatists of the last fifty years. It would be easy enough to take exception to the execution of these volumes, if it were at all desirable to do so. But we see no necessity for trying a book which makes no literary pretence, by a high literary standard. We are willing to accept the fruits of Mr. Fitzball’s dramatic experience good-humouredly, when they are worth gathering; and when they are not, we can easily accept the alternative of leaving them on the tree.

From

Household Words

28 May 1859

Olive Logan (1839-1909) was an American actress, who worked with Augustin Daly’s Broadway theatre. She also wrote plays, some of which she adapted from Collins’ novels, and in later times she wrote her own novels, as well as working as a journalist. Over the years she developed a close friendship with Collins, though none of their letters survive. This short biographical work concerns Logan’s meeting with Collins in 1879, 1887, and 1888

Olive Logan: actress, dramatist, novelist and journalist

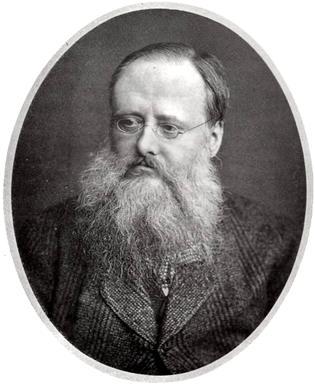

WILKIE COLLINS’ CHARMS

His High Regard for Dickens, but Trivial Estimate of the French Novelists — His Glassy-Eyed Ghostly Visitors — At the Society of Authors’ Dinner Last Year — A Pen-Portrait of the Venerable Author.

In the Winter of 1879 Wilkie Collins wrote to ask me what day would be convenient for me to receive a friendly little visit from him. I was then residing at the Midland Grand, the precursor of the now numerous hotels of size and splendor which have contributed so largely to the attractiveness of London for the American traveller. My reply to the distinguished novelist was as cordial as I knew how to make it, We agreed upon a day, an hour, and on that day and promptly at that hour Mr. Wilkie Collins came.

He had been ushered into the music room of the hotel before I descended from my apartment above stairs. I found him seated upon a sofa near a large window, from which one obtained a marvellous view of the densely populous parish of St. Pancras. Directly beneath was the entrance to the Midland Railway Station with its wide court-yard inclosed behind high iron railings, in itself a remarkable scene of busy life: hundreds of cabs arriving and departing every hour, bringing or carrying away uncountable travellers; scores of porters lifting trunks (carefully, as is the custom in England) or running about with small parcels, umbrellas and the various impediments of those who journey by rail.

The old church of St. Pancras was visible on the south, an interesting edifice, with a noble façade adorned with Corinthian columns, the pristine purity of whose Italian marble has been softened into a picturesque gray by innumerable fogs. Euston station was close at hand, teeming with throngs, composed in the majority of Americans bound from or towards home. But the crowds passing through the streets, the resident population of the neighborhood, were, after all, the most striking feature of the window view. They were the poor, the lowly, the tattered, the quaint, the unmatchable hordes which Dickens pressed into service as models for his characters. Wilkie Collins was thoughtfully looking down upon the varied scene when I approached him.

“A strange picture, is it not?”

“Yes,” returned he, “queer old parish, St. Pancras. Always considered one of the poorest London neighborhoods until the Midland Railway people built this fine hotel. This will attract well-to-do travellers, of course.”

The high-art idea in furniture and decoration was a novelty in England at that time, and the room in which we sat was an exaggerated expression of the “truly precious” fancy in adornment. Dull blues and brick-dust-reds in wall paper and hangings alternated their lowness of tone with that of wrought-iron sconces and diamond pane lights. Gilding and rainbow colorings shone by their absence.

I asked my visitor if he admired the new taste in domestic decoration. He replied emphatically that he did not.

“I was thinking before you came in,” he went on, “how Dickens would have detested this room. He was so fond of a large, square room. An irregular oblong apartment like this would have driven him mad if he’d been obliged to stay long in it.”

HIS HIGH ESTEEM OF DICKENS

Frequently during our long conversation he spoke of Dickens, whose opinions on every subject — moral, social and intellectual — he evidently held to be of superlative value. For instance, referring to the realistic school of fiction as represented by contemporaneous French authors, he exclaimed.

“Zola! Faugh! Heaven preserve one from such realism as that! How Dickens would have recoiled from it — he was realistic, indeed, but so pure. Well, Daudet is not quite so bad as the rest; still they are all but poor echoes of Balzac, ‘Le Père Goriot’ is worth more than the whole lot of these modern Frenchmen’s novels put together. It will be a long day before M. Zola or M. Daudet produces anything that can approach that pathetic masterpiece.”