Condor (16 page)

Authors: John Nielsen

Words like those did a lot to influence public opinion, but by the

late seventies, they didn't seem to carry much weight with relevant federal and state officials. This was true in part because the hands-off point of view had been officially considered and rejected by a panel of prominent wildlife experts called in to do a “scientific audit” of the recovery plan.

“The existence of the California condor depends on conscientious human intervention,” read the panel's final report. “This will always be so. The only reasonable hope for achieving a large population of condors in the wild is captive propagation.”

4

When the scientific panel dismissed arguments put forward by Brower and his allies as “vacuous,” Wilbur said he felt both vindicated and enormously relieved. And yet, not long afterward, Wilbur said, he was unexpectedly reassigned to a job in Sacramento. A new team of biologists was coming in to carry out the last-ditch rescue plan, and they didn't want Wilbur's input.

The condor known as AC-9 or Igor watched trapper Pete Bloom catch several of the last wild condors from the top of a nearby tree. Igor himself was trapped on Easter Sunday, 1987. (Photo by Dave Clendenen; courtesy of Peter Bloom)

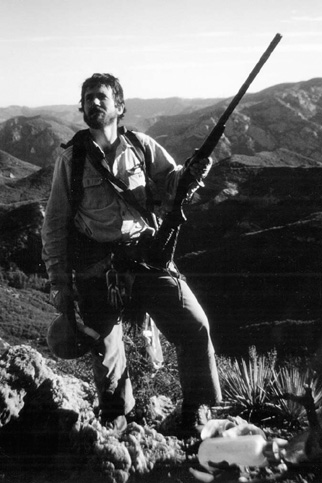

In 1986 and 1987, the last free-flying California condors were trapped by biologists like Peter Bloom (pictured) of the National Audubon Society and Dave Clendenen of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (Peter Bloom)

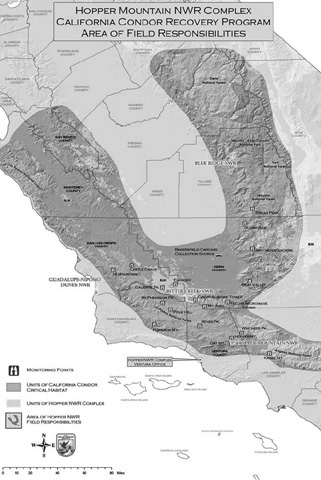

After World War II, the range of the condor followed this wishbone-shaped set of mountains. (Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

When creatures like the saber-toothed cat and the mastodon were alive, the California condor ranged across large parts of North America. (Knight Mural of Pleistocene Life, Rancho La Brea Tar Pits #4948 courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History)

Indian tribes in California revered the birds and left paintings of condors on rocks. (Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

“I believed this to be the largest bird in North America,” wrote Lewis in his journal in 1806; Clark wrote the same thing and added a rough sketch of the bird's head. (Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society)

Hundreds of years after Lewis and Clark explored the Columbia River, condors were returned to the Vermillion cliffs and the Grand Canyon. (Christie Van Cleve)

In 1840, John James Audubon immortalized the “California Vulture” in “The Birds of America.” (Courtesy of Haley and Steele)

By the early 1900s, hunters and egg collectors had all but wiped the species out. (Photo by R. Corado; courtesy of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology)

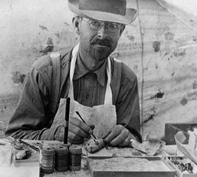

Joseph P. Grinnell, a legendary naturalist, was among the first to describe the bird as a “symbol of our lessening wilderness.” (Courtesy of the Bankroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

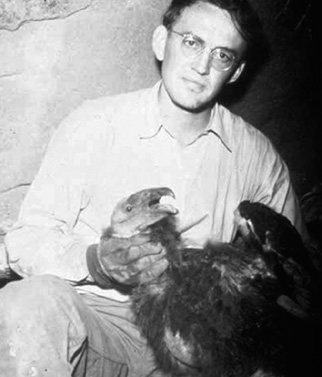

In 1939, Carl Koford was the first to study the behavior of wild condors and urged hunters, loggers, hikers, photographers, and scientists to stay away from the species. (Courtesy of Rolf R. Koford)

At times, Koford and some of his friends handled condors in their nest caves. Koford later denounced the “hands-on” approach as a threat to the future of the species (Ed Harrison, above). (Photo by Carl Koford; courtesy of Lloyd Kiff)