Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist (11 page)

Read Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist Online

Authors: Patrick Moore

Some of the crew of the Phyllis Cormack around the galley table. From the left, Terry Simmons, Jim Bohlen, Lyle Thurston, Dave Birmingham, Dick Fineburg, Bill Darnell, Bob Hunter, me, and Captain John Cormack.Photo: Robert Keziere

Even though we were blocked from sailing to the nuclear test site, and even though that 5-megaton explosion did take place on November 6, 1971, we were the ultimate victors. Fueled by our action and the resulting publicity, tens of thousands of protesters blocked border crossings between the U.S. and Canada the day the bomb was detonated. The public opposition to the tests forced President Nixon to cancel the remaining H-bomb tests in the planned series in February 1972. This was at the height of the Cold War and the height of the Vietnam War.

In retrospect this proved a major turning point in the global arms race. Our September 15 departure from Vancouver on our first mission was the birth of Greenpeace. This mission put us squarely on the front lines of the battle to end the threat of nuclear Armageddon. The first major agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union under the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, the AntiBallistic Missile Treaty, was signed on May 28, 1972.

Even though we had been on opposite sides of the debate about whether to go home or go on, Bob Hunter was to become the kind of lifelong friend that rarely comes along. He was a prominent editorial columnist with the

Vancouver Sun

, our city’s main newspaper, and he had established himself as an exciting commentator on the emerging environmental movement.

As we made our way back down the coast from Alaska, Bob and I had time for sustained reflection. But there was one conversation that still seems as if it happened yesterday. “Pat, this is the beginning of something really important and very powerful,” he predicted. “But there is a very good chance it will become a kind of ecofascism. Not everyone can get a PhD in ecology. So the only way to change the behavior of the masses is to create a popular mythology, a religion of the environment where people simply have faith in the gurus.” Today I shudder at the accuracy of his foresight.

On our way home from Alaska we were welcomed into the big house of the Namgis (Nimkish) First Nations, part of the Kwakiutl First Nations, at Alert Bay near my northern Vancouver Island home. They danced for us and initiated us into their tribe as brothers, sprinkling holy water and eagle feathers on our heads. We were given the right to display the Sisiutl crest, a double-headed sea serpent representative of the orca whale.

For Greenpeace, this began a long relationship with aboriginal and indigenous people around the world. Bob Hunter came across a small book titled

Warriors of the Rainbow.

It contained an American Indian prophecy predicting that someday when the sky was black and the birds fell dead and the waters were poisoned that people from all races would join together to save the earth from destruction.

[1]

We soon fashioned ourselves as the “Rainbow Warriors.”

We were made honorary brothers of the Kwakiutl First Nations at Alert Bay on our return from Alaska. This began a long association with aboriginal people around the world. I am in the center with cap in hand. Photo: Robert Keziere

After the voyage to Alaska many of the campaigners who put Greenpeace on the map against U.S. nuclear testing moved back to their former lives or moved on to new ones. But a few of us—Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe, Jim and Marie Bohlen, Bob Hunter, Rod Marining, and myself—had become addicted to making waves and taking on the nuclear establishment. It wasn’t long before we turned our sights on French atmospheric nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll in the South Pacific.

France had refused to sign the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963 banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere. Both France and China continued to detonate nuclear weapons in the air, sending radioactive fallout around the world. New Zealand, in particular, had become a hotbed of opposition against the French nuclear tests.

Before sailing on the first Greenpeace voyage, Ben Metcalfe, a former CBC radio news correspondent, had made a reputation as a creative booster for the emerging environmental movement in Vancouver. Ahead of his time, in 1969 Ben paid for 12 billboards at major Vancouver intersections so commuters could read in simple bold print, “Ecology? Look it Up! You’re Involved.” It is hard to imagine today that the word

ecology

was not yet mentioned in the popular press, but at the time one only found it in obscure academic journals.

During the winter of 1971-72 Ben and the rest of us met around kitchen tables to plan our next campaign. We knew that French atmospheric nuclear testing, conducted at Mururoa Atoll in French Polynesia, was the logical target. Soviet and Chinese testing would have been great targets too, if they didn’t involve the practical reality of wanting to avoid the prospect of life in the gulag or death in a far-off prison cell. And certainly within the peace movement at the time the West was considered theaggressor. The Vietnam War put an exclamation mark on that perception.

But French Polynesia lay way out in the remote South Pacific. It had been one thing to sail a boat up the coast from my hometown near Vancouver a thousand miles to Alaska; it was quite another to sail from New Zealand, the closest “friendly” country to Mururoa, 2500 miles across the open waters of the South Pacific. There was also the inconvenient fact that our bank account contained only $9000 and we had no boat, no captain, and no crew. But we were not about to let pesky details get in our way.

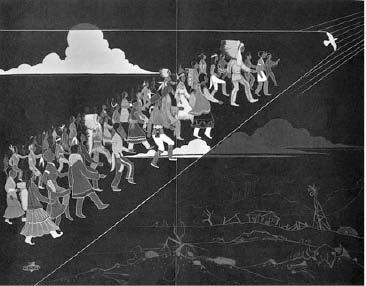

A depiction of the Warriors of the Rainbow from the book of the same name. Aboriginal people are following the dove of peace to save the environment.

We decided to issue a press release announcing that Greenpeace’s next campaign would be to sail a boat from New Zealand to Mururoa in order to challenge the French nuclear tests. As France was illegally cordoning off thousands of square miles of international waters during the tests (the 200-mile limit was not in force at the time), we planned to position a boat near the atoll in international waters, then only three miles offshore. Any nuclear test would fry the boat and its occupants, something France might want to avoid. It turned out we were a bit overconfident on this point.

Our press release received little notice anywhere but New Zealand, where the major newspapers put it on the front page. Suddenly there was a buzz that this bunch of crazy Canadians were coming down under to raise Cain as they had up north in Alaska. The headlines brought a few phone calls from skippers in the South Pacific but only one call made sense. A certain David McTaggart, an expatriate Canadian from Vancouver, who had been sailing the southern ocean for seven years, telephoned us to volunteer his 36-foot ketch

Vega

for the mission. David had been a Canadian badminton champion and a successful entrepreneur until he fled for bluer waters. Now he wanted to challenge the right of France to take over international waters for its nuclear tests. Suddenly, we had our skipper, we had our boat, and the publicity surrounding the adventure brought financial support from around the world.

Dorothy Metcalfe coined the slogan

Mururoa mon amour

(“Mururoa My Love”) after the acclaimed 1959 film

Hiroshima mon Amour.

This became our campaign slogan and we also used it on lapel buttons that we ordered. Ben Metcalfe took the $6000 or so left in our account to New Zealand and joined McTaggart to outfit the

Vega

for the voyage. In the spring of 1972 I traveled to New York with Jim and Marie Bohlen, who came from that part of the world, and we spent a week visiting the UN embassies of the Pacific Rim countries to inform them about the French nuclear tests. The first UN Conference on the Environment was about to take place in Stockholm, Sweden, and there was an opportunity to make the tests an issue from an environmental perspective. It is hard to believe today, but the Western superpowers (the United States, Great Britain, and France) took the position that nuclear weapons and nuclear testing were not environmental issues and should therefore not be raised at the UN conference. We took exception to this. If nuclear fallout spreading around the earth wasn’t an environmental issue, what was? And come to think of it, what about the environmental impact of all-out nuclear war?

Yes, that was the “thinkable” reality that gave my generation nightmares for years. I half-jokingly said, “It might rain today, and by the way, total nuclear annihilation is possible on Wednesday.” It is hard to express the singular resolve that emerged to fight this possibility. It expressed itself in many countries, in many publics, in many political debates. But I don’t think it expressed itself anywhere more fully than in our fledgling troupe of Greenpeace button-wearing ecologists, pacifists, anarchists,and revolutionaries.

The spring of 1972 saw Greenpeace coming into its own with a coordinated effort straddling the globe. While David McTaggart and Ben Metcalfe set sail from New Zealand for Mururoa, a small group of us set off to Europe, where we hoped to “send a flaming arrow into the heart of Western civilization, ” to use the hyperbole of that time. Our first stop was Rome, where we had requested an audience with Pope Paul VI in the Vatican. As a man of peace he welcomed us, blessing our flag and sending a message against nuclear testing around the world.

We then proceeded to Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, where we spent the afternoon leafleting visitors with antinuclear pamphlets and telling them, in broken French, about

le petit b

a

teau

that was sailing into the test zone as we spoke. As the cathedral closed, we sat in the pews and told the custodians that we were taking refuge in the church and wouldn’t leave until nuclear testing stopped. They politely informed us that Notre Dame was not a church but a national monument and we’d better get out or we would be arrested by the surete (the national police).

We left, but not until we were interviewed by

Le Monde

, France’s main national newspaper. The next day’s story marked the first time the French public had been informed about opposition to their nuclear testing program in French Polynesia.