Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist (17 page)

Read Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist Online

Authors: Patrick Moore

As panic set in, Paul Spong tried to use his portable radio as a radio direction finder but this didn’t help. Among us we reconstructed our route away from the

James Bay

and determined in which direction we should travel. It took nearly that whole hour, but as dusk was falling we first heard the foghorn and then saw our ship coming through the mist. That was the closest I had come to being lost and dead 1200 miles from the beach. Eileen and Bob and the others raised up a considerable whoop as we came into view. The Rainbow Warriors had karma working for them that day.

Seal Campaign 1977

Our second seal campaign, in early March, 1977, was by far the most bizarre scene I have been in, and I have been in some pretty bizarre scenes. First, Paul Watson (again the somewhat self-appointed leader of the campaign) decided to base the expedition out of the north shore of Quebec in the village of Blanc Sablon. Apparently this was to avoid hostilities in St. Anthony, but that’s where all the North American media were based. Paul had managed to convince the Swiss animal-rights activist Franz Weber to bring about 80 European journalists, many of them top-flight, to join us in Blanc Sablon. The only public lodging in the village was a motel with beds for 30 in 10 small rooms. I was glad I’d packed my sleeping bag as we managed to cram more than 100 bodies into the place, including Weber and his journalists, 15 Greenpeacers, our helicopter pilots, and a few others I can’t recall. Weber had failed to find a helicopter company that would rent machines to him, so he had no way of getting the journalists out to the ice. As in the previous year, the Greenpeace crew established a base camp on Belle Isle, but this time it was bigger and better equipped. Paul, who seemed to think his actions were the most important part of the campaign, initiated things by nearly getting killed and putting the other crew members at risk of injury or death.

Paul had led a small group to the ice in two helicopters, where they encountered very difficult conditions. There were 12-foot swells under the ice floes, so the entire seascape was in motion. Landing more than a mile from the sealing ships, Paul raced ahead of the crew. Our physically fit lawyer, Peter Ballem, was the only one able to keep up to him. Paul approached a sealer who was skinning a seal pup, grabbed his hakapik and threw it into the water in a gap between the floes. Then Paul threw the sealskin into the water. Peter warned him this activity was unlawful. The sealer had the sense to ignore Watson instead of skinning him. These kind of extreme tactics had not been discussed with the crew, never mind our board of directors. Then Paul really went over the top. He pulled out a pair of handcuffs and attached himself to a cable that was about to haul a bunch of sealskins on board a sealing ship. The sealers saw they had a live one and began to winch the skins in, dragging Paul along the ice. About 20 feet from the sealing ship, the solid ice ended and Paul was dragged into frozen slush. The sealers were jeering like fans watching gladiators eaten by lions. The winch operator purposely lifted Paul 10 feet above the water and then dropped him back in. Then the handcuffs broke loose and Paul was floundering in the frozen sea; he would only last five minutes. Peter had dragged a small inflatable skiff across the ice in case they encountered a wide lead between the floes as they approached the sealers. He got in it and pushed himself across the open water toward Paul, which meant getting soaked to the waist himself. A big man, Peter managed to drag Paul, a big man too, into the inflatable and got him back to solid ice, where he laid, screaming obscenities at the sealers. Peter pleaded with the sealing crew to take Paul aboard or he would surely die of exposure as the helicopters were more than a mile away and Watson was already turning blue. The sealers eventually realized that it would not look good if they killed someone, so they winched Paul aboard in a stretcher, landing him face down in a pile of bloody sealskins. Peter also boarded the ship, where he and Paul would remain overnight.

Because he raced ahead and acted unilaterally, Paul had failed to have his actions documented on film, a key purpose of the expedition. Rumors about his fate flew around overnight. Some journalists reported that Paul’s arm was broken or that he was possibly dead. When he appeared the next day after having been flown to the hospital in Blanc Sablon and released, he looked perfectly fine. This resulted in a credibility gap with the media, we had no film to show what really happened and the whole episode became an embarrassment. Meanwhile the 80 European journalists were getting antsy, as not one of them had made it out to the ice. Paul, who had signed the charter contract on behalf of Greenpeace, had control of the only two helicopters and had now holed himself up in his motel room, obviously traumatized by the recent events. With our erstwhile leader incommunicado, I had to play my hand as representative of the Greenpeace board, as I was vice-president and organizationally senior to Paul. Bob Hunter, who stayed behind during this campaign, had insisted I go along to keep an eye on Paul and to take control if necessary. It had become very necessary. The media were so desperate for a story that one German film crew hired a local man to pose with a stuffed seal pup as if he were about to club it to death. This made the wire service as if it were the real thing.

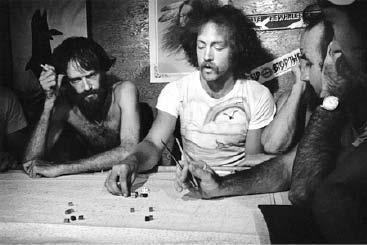

Bob Hunter, myself, and Matt Heron strategize on the movements of the Soviet whaling fleet. Twelve hundred miles north of Hawaii the weather was foggy and foul. Photo: Rex Weyler

In the middle of all this, we learned that the French actress Brigitte Bardot had arrived in Blanc Sablon with a six-person film crew and her Polish sculptor boyfriend, Mirko Brozek. They had flown in unannounced and had rented a vacant house in the town. The European media went into a complete frenzy as the world-famous beauty arrived for a media conference at our motel, denouncing the Canadian government and vowing to campaign until the slaughter ended.

The Bardot party had also been unable to find helicopters for rent, so now there were 15 Greenpeacers, Franz Weber, and his 80 European journalists, and Brigitte Bardot, with a top French TV producer and full film crew, all vying for eight seats in our two small helicopters. The media were calling for Watson’s and Weber’s heads. Then our helicopter pilots informed us that Bardot’s producer, Henri, was negotiating directly with them to fly Brigitte and the film crew out to the ice. “He says Brigitte will sit beside us in the helicopter,” one of our pilots swooned. Brigitte had been uncharitably described as an “aging sex kitten” in one Canadian paper’s headline, but believe me she looked stunning for a woman in her early 40s, or indeed of any age. Our pilots were leaning toward breaching our contract, leaving us with no helicopters to get our expedition out to the ice. Peter Ballem and I decided to take matters into our own hands. We borrowed a snowmobile and made our way to the house that the Bardot party had rented.

Henri eventually greeted Peter and me through a small crack in the doorway. We explained that the helicopters were ours but that we were willing to try to work out an accommodation. At first Henri responded negatively, but we insisted so he went to speak to Brigitte and she gave the nod. There we were sitting around the kitchen table with Brigitte Bardot in an isolated community on the North Shore of Quebec. It was a bit disarming, but we had business to do. It turned out that Brigitte didn’t want to see the seal hunt; she just wanted to be photographed with a baby seal. I proposed that we share the helicopters the next morning, taking Brigitte and a bare-bones film crew along with some of the Greenpeace team. We decided we would make a stop at the Greenpeace camp on Belle Isle to introduce Brigitte to the expedition members. Then one helicopter would find a baby seal on the ice for the photo-op while the other would look for the sealing ships. It was a good compromise even though it did nothing to help Franz Weber and his 80 journalists, who were now in full mutiny.

That evening we had a large party. By then Brigitte had realized that Peter and I were cool, and as the beer and wine flowed we engaged in an animated discussion of everything from the seal hunt to the latest movies. Paul Watson finally emerged from his lair and joined the festivities. He agreed to come with us to Belle Isle in the morning.

The weather forecast was not particularly encouraging as we lifted off at 6 a.m. Halfway to the base camp we found out why. It was blowing snow and the wind was picking up fast, so we stayed low to the water over the Straits of Belle Isle. When we came up against the 800-foot cliffs of Belle Isle, we went into a steep ascent into the clouds; but there was still some visibility. We came up over the top of the island, now trying to get our bearings on this huge rock in order to locate the base camp. Within minutes we found ourselves in the midst of a squall with blinding snow, a “whiteout” as they call it in helicopter school. In this situation there is only one option: land the helicopter now. Whiteouts have the effect of completely disorienting the pilot so that he doesn’t know up from down. Our pilots were probably being heroic because they had a beautiful VIP on board, but they did get us safely on the ground in challenging conditions.

It was not good that we were stranded, with no radio contact, in an intensifying blizzard. Moreover our helicopters were flimsy with limited fuel for flying and an insufficient amount to keep us warm in the subzero Newfoundland winter. But then again, I was stranded with Brigitte Bardot, the most beautiful French actress, an intellectual, whom the philosopher Sartre had used as a model for a character in one of his novels. Another consolation was the large provision of food we had on board to resupply the camp. And if things got really desperate we had a good stock of rum and whiskey meant for the camp as well. I mean, if we couldn’t find the camp in a whiteout it was okay for us to survive on their rations, right? I’m forever thankful that after about an hour the storm lifted long enough for us to get the choppers in the air and find the camp.

The mood at the camp was mainly jubilant, at least on the surface. Most crew members seemed pleased to meet a superstar and there were lots of photos taken and some group discussion about the environment and animal welfare and the seals. However, beneath the veneer of smiles this encounter brought out a deep division in the personal philosophies of the Greenpeace crew. Some of our number thought it belittled the high cause of Greenpeace to associate with an actress who was primarily known for her love of cats, dogs, and horses. Other members, myself included, realized that we could benefit by linking with Brigitte, thus making a more powerful statement for the seals than either one of us could alone. There was no doubting her sincerity, and it didn’t matter that we Greenpeacers didn’t belong to the upper-class European elite as Brigitte did.

We soon realized that we weren’t going any farther out to the sealing grounds on this day. There were blizzard conditions all around and it was another miracle that we were able to return to Blanc Sablon and the relative comfort of our motel rooms, where most of us were sleeping on the floor. But sleep could come later, we had another big dinner planned and the prospect of succeeding tomorrow. Just before dinner I was informed that Paul Watson had declared his legal right to control the helicopters, as he had signed the rental contract. Some members of the expedition had impressed on him their disapproval of Brigitte, as she was not “serious” like we were. I asked Paul to reconsider, but he was determined to assert his authority. I joined the Greenpeace/Bardot dinner with bad news. When I told Henri I could not provide any helicopters, the next day he retorted, “You will never see Brigitte again.” I felt crushed, of course, and very disappointed that we couldn’t work together any longer.

The next morning a privately owned Bell Jet Ranger helicopter took off at dawn from Blanc Sablon with Brigitte and her crew on board. Henri had worked late into the night to find an alternative now that we had cancelled. They reached the ice, where the seal pups lay about like big white Easter eggs and Brigitte held a baby seal in her arms. The photo appeared on the front cover of

Paris Match

and the accompanying article mentioned her visit to the Greenpeace camp on Belle Isle. I felt vindicated but still wished we had delivered her to the seals ourselves.

The expedition now wound to an end with some bitterness on my part. Paul Watson had behaved like a spoiled child and really undermined our effectiveness. I documented every detail about Paul’s misbehavior and wrote to Bob Hunter about my concerns. I was actually a bit surprised on my return to Vancouver that most of the board members agreed with me. They could see Watson was too much of a rogue elephant for a group that prided itself on being a democratic collective.