Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist (23 page)

Read Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist Online

Authors: Patrick Moore

The oil interests were not happy with this restriction as it meant two tankers were required to deliver the same amount of crude as one big one could carry. The U.S. Coast Guard, our old friend from the Amchitka days, was somehow pressed into service by the oil companies to rectify the situation. They would oversee a “test,” whereby a 189,000-ton supertanker, the B.T. (Big Tanker)

San Diego

, would sail into the Strait with a hold full of water to see if it was “safe” to bring larger tankers into Puget Sound. This was like a red flag to a bull for us. We issued a press release stating that we would send a flotilla to stop the supertanker test. It was one thing to do a controlled experiment in broad daylight, but what about 100 m.p.h. winds at night in the fog? The Coast Guard replied in short order, declaring a 2000-yard “safety zone” around the supertanker to protect us from ourselves. Double red flag. We vowed to defy the so-called safety zone and once again the battle was joined.

We chartered the beautiful 120-foot wooden yacht,

Norsal

, and assembled a veteran crew to challenge the behemoth in the straits. With the motto “Save the Seas” we set sail from Vancouver on January 23 and made for the test area. By this time, we had attracted the main media outlets on both sides of the border, a classic international campaign in a microcosm. The morning was clear and calm as we positioned ourselves in the path of the B.T.

San Diego

. We launched three Zodiacs and proceeded toward the big ship. My God what an enormous ship it was. I was the lead boat with Rex Weyler in the bow doing still photography. A local British Columbia TV camera crew was right behind us and Mike Bailey followed in a back-up confrontation boat. It was a perfect setup for a confrontation. Earlier in the day, I had coined the term “giggle room” for the fictitious place we go to avoid appearing smug in front of the media representatives when the authorities play so perfectly into our hands. We had plenty of opportunities to visit the giggle room on this day.

I piloted our Zodiac right in front of the slow-moving supertanker, edging in close so that we were riding the bow wave about 20 feet in front of the massive ship. News helicopters appeared and the TV crew in our other Zodiac came in close to shoot the action. The B.T.

San Diego

gradually came to a stop. We had halted a 189,000-ton ship with a 14-foot Zodiac and a lot of nerve. The Coast Guard reacted by sending four very fast 24-foot cutters into the fray to intercept us. A chase worthy of any Hollywood movie ensued during which we eluded the Coast Guard until they nearly killed us and we finally said uncle. We were taken aboard the Coast Guard cutter and I was handcuffed, but not in the usual manner. As Rex photographed my arrest, he was yelling, “I’ve been in Vietnam and that is against the Geneva Convention.” Then the Coast Guard guys arrested Rex.

Instead of using the normal handcuffing procedure, the Coast Guardsmen, who obviously resented the fact that I had outrun them for nearly an hour, cinched plastic handcuffs around the top of my wrist, where it is excruciatingly painful. This method is used as a form of torture and is forbidden by international law. After cuffing me in this deliberately painful way, they threw me facedown on the metal hatch and held me there with a boot in my back for what seemed a very long time. I asked them several times to please loosen the handcuffs. Once the boat chase had ended, I had not resisted arrest or used abusive language, yet they were behaving like thugs. It was quite a contrast to the first voyage we had made to Alaska in order to protest U.S. hydrogen bomb testing, when the Coast Guard commander and crew had treated us with respect. It was a reminder that the Coast Guard is a branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, and sometimes its guardsmen get rough.

Rex Weyler and I ride the bow wave of the supertanker B.T.

San Diego

in the Straits of Juan de Fuca (bottom center). Moments later we brought the behemoth to a halt. The authorities were not amused.

They finally let me get up and replaced the plastic cuffs with regular metal ones, attaching Rex and me together like convicts on a chain gang. It was then that we found out four others, including two members of the TV camera crew that were in one of our Zodiacs, had also been arrested. Thankfully the Coast Guard had left the

Norsal

alone, presumably because it had not violated the 2000-yard “safety zone.”

All six of us were ferried into the dock at Port Angeles, where we were escorted to a police van, taken to jail, fingerprinted, and thrown in a cell. David Gibbons had been on standby and he had us out on our own recognizance about three hours later. It’s always good to have a lawyer standing by who can get you out of jail before nightfall!

We were greeted by the rest of our crew who reported that the media coverage of our protest had been awesome. The film and photos taken from news crews in helicopters showed our tiny Zodiac in front of the massive supertanker in classic David and Goliath style. Combined with the boat chase and arrests, it made a great TV and newspaper story. And public opinion in both Canada and the U.S. was clearly on our side.

The Coast Guard announced it would proceed with criminal charges against us because we had entered the safety zone. If convicted, the Canadians among us might be barred from entering the U.S. for life. This would not be a good thing. So we were greatly relieved when we were informed in the end that they would not go the criminal route. Instead they issued each of us with a letter stating that we had been fined US$10,000 apiece for our transgressions. The letter went on to say that if we didn’t pay the fine we would be “tried in an appropriate jurisdiction.” After pondering what that meant, we realized they didn’t have any jurisdiction. So I framed my $10,000 fine and hung it on my office wall, where it remains today. Yet another visit to the giggle room was in order. Then we got the news that the U.S. government had decided not to remove the size restriction on tankers in Juan de Fuca Strait. We had prevailed and our victory had only taken a few weeks to achieve.

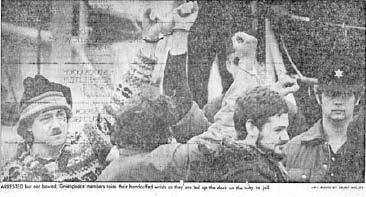

The six of us who were arrested for protesting against the supertanker were handcuffed together in pairs. I am on the left, chained to photographer Rex Weyler. Cameraman Robert McLachlan, second from the right, is attached to one of the other six people who were arrested by the U.S. Coast Guard.

In the spring of 1981, the United States was beginning to flex its nuclear muscles under President Reagan. It sent large warships into foreign ports to pay a friendly “visit.” New Zealand had banned ships carrying nuclear weapons from entering its territorial waters. The U.S. Navy would “neither confirm nor deny” the presence of nuclear weapons, so the New Zealand edict essentially barred all U.S. warships from entering its waters. Many of us in the Greenpeace Canada group admired New Zealand’s courage and thought our country should follow their lead.

It was announced that the USS

Ranger

, a nuclearpowered aircraft carrier, would visit Vancouver to give the crew some shore leave. It was all in the serious tone of cold war rhetoric, staunch allies prepared to confront the Soviet threat. Canadians were being called on to pay fealty to their protectors to the south, a demand many Canadians have always resented. We like to think we are independent while at the same time neglecting to invest in effective defense forces. This means that we ultimately depend on the U.S. for protection. This “have your cake and eat it” attitude is compounded by a smug assertion of superiority: we don’t pack concealed weapons, hang criminals, invade other countries, or engage in bullying trade practices. Like most European countries, Canadians enjoy universal health care while the U.S., the richest country on earth, is still deeply divided on the subject. Thankfully some progress has been made under President Barack Obama, but there are strong political forces opposed to universal health care.

I believe this resentment of U.S. dominance, both militarily and culturally, stems partially from the “meat in the sandwich” position Canada was in throughout the cold war. The long-range strategic nuclear warheads were aimed in their thousands from both the Soviet Union and the United States across Canadian soil and airspace. Out of a feeling of helplessness springs resentment against one’s closest friend and ally.

Leading up to the USS

Ranger

‘s visit we noticed that local newspapers were carrying many ads from escort agencies and individual young women offering their services to the servicemen who were about to arrive. I was said to have implied that the visit had less to do with national defense and more to do with randy young sailors looking for women and pot in our liberal social environment. Did I ever hit a hot button! The wrath of God descended on me in editorials and letters to the editor about insulting our allies and impugning the motives of the navy’s finest. At least the Canadians who appreciated America’s role in defending our freedom came out of the closet. It gave me pause, pondering the great questions of war and peace, hawks and doves, randy young sailors and loose women.

But philosophical musings would not deter us from demonstrating against the awful might of the nuclear superpowers. To give us credit, we always made it clear that we would be equally opposed to a Soviet warship carrying nuclear weapons coming to Vancouver. Any nuclear weapons-carrying ship made our otherwise peaceful shire a first-order target in the event nuclear hostilities broke out.

The

Ranger

was too tall to fit under the Lions Gate Bridge at the harbor entrance, so she would have to anchor in the outer harbor. It was Fred Easton who came up with the idea that we would send in Zodiacs to get under the anchor of the carrier so that the crew couldn’t drop the anchor without sinking or perhaps injuring us. We hired the

Meander

, the 85-foot wooden yacht we had used in the campaign against the Kitimat pipeline, and called for a flotilla of fishing boats and pleasure craft to join us.

The harbor was thick with boats of all description as the big carrier entered the bay. More of a picket line than a blockade, we flew banners and carried signs of an unwelcoming nature. I made the best protest picket sign of my activist career. It read simply, “Go Home Death Machine.” The lead Zodiac placed itself under the anchor as hundreds of sailors hung over the gunnels to get a look at the spectacle below. The standoff lasted for about 10 minutes until the harbor police approached in a small cutter and ordered the Greenpeacers to get out from under the huge anchor. The Zodiac held firm as the police got out their pike poles and proceeded to poke holes in the Zodiac. No one had thought of that before! The inflatable boat was deflating fast as another Zodiac came in to rescue the crew, taking the crippled craft in tow. Amid the confusion the

Ranger

crew saw an opening and quickly dropped their anchor. The demo was over, but the media coverage played all day and evening. I wondered briefly if maybe with this fight we were in a little over our heads.

It all comes back to whether one believes nuclear weapons are responsible for world peace or whether they should be abolished. Many people firmly believe that dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—an act that ended the Second World War— resulted in more lives being saved from continued combat than the number that were lost in the blasts. And many believe that the deterrence resulting from “mutually assured destruction” can be credited with preventing another all-out World War. Pacifists and antiwar activists take the opposite view, of course, that nuclear weapons are evil and should be abolished as soon as possible.