Congo (74 page)

Authors: David Van Reybrouck

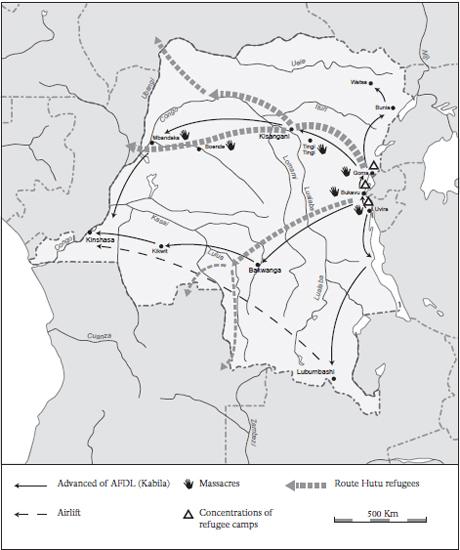

Deeper in the interior, the pursuit of the Hutus led to grave human rights violations. As soon as the AFDL came in, villagers noted, the Rwandans would ask where the refugees were, then take off to massacre them.

47

This led to massive carnage. The situation was particularly gruesome at Tingi-Tingi, only a stone’s throw from Kisangani, where a group of some 135,000 Hutu refugees had gathered. Many of them were in a pathetic state. Cholera had thinned their ranks and their children were dying in great numbers. When the AFDL approached from the east in late February 1997, the survivors ran into the jungle to hide. The Rwandan Tutsis then misused the international aid organizations to help regroup the refugees in a number of makeshift camps. As soon as a new crowd of Hutus was gathered, aid workers and journalists were barred from the area “for safety reasons” and the ethnic cleansing could begin with impunity. It was not only Hutu soldiers or Interahamwe who were murdered, but also malnourished children, women, old people, the wounded, and the dying. The killing sometimes took place at gunpoint, but much more often with the machete and the hammer. Ammunition was expensive and heavy to carry through the jungle.

The international community was denied access to the area and the true extent of the atrocities became clear only later. Eyewitness accounts from perpetrators are rare. “Yes, I was at Tingi-Tingi,” said Lieutenant Papy Bulaya, a former soldier in the AFDL. Only after many bottles of beer was he able to talk about it.

Listen, our objective was Kisangani, and Tingi-Tingi was in the way. So we had to neutralize it. I was a

kadogo

, only fifteen, our commander was Rwandan, General Ruvusha. He’s a colonel in the Rwandan army now, but he was terrible. Laurent Nkunda was there too. Drive out the enemy, those were our orders. Our Tutsi commander told us: They’re

génocidaires

, they have to die. They would call out:

Kadogo

, kill this person. And we had to obey, otherwise we were executed on the spot. We had to keep going all the time. A lot of Rwandans were killed there back then. Afterward their bodies were doused with gasoline and burned, or buried. The supply trucks moved along behind us: food for us and gasoline for the “mopping-up,” to “clean the slate.” When I think back on it, it hurts so much. I regret it, but we were loyal to the AFDL.

48

The emergency camps at Tingi-Tingi had provided shelter for eighty-five thousand people; after the cleansing they were empty, deserted, desolate. Tens of thousands of Hutus were massacred. A group of forty-five thousand fled west, to Équateur, where they were intercepted at Boende and Mbandaka and murdered en masse. Eyewitnesses even saw soldiers kill babies by crushing their skulls with a boot heel or dashing their heads against a wall.

49

A few Hutus were able to escape and made it to Congo-Brazzaville, some even as far as Gabon. By then they had covered more than two thousand kilometers (about 1,250 miles) on foot, straight across Zaïre, under conditions more miserable than anything Stanley had endured. All in all there were only a few thousand survivors, a tiny fraction of their original numbers. During the invading army’s advance, an estimated two to three hundred thousand Hutu refugees were murdered.

50

T

HE WAR LASTED SEVEN MONTHS

and was, in essence, a steady offensive westward to Kinshasa. Real battles were waged at some places, like Bunia and Watsa, but almost everywhere else the AFDL simply rolled on through. Kindu fell on February 28, 1997, Kisangani on March 15, and Mbuji-Mayi on April 4. The conquest of Kisangani was of particular strategic and symbolic importance, because the city lay on the river, the Central African thoroughfare to Kinshasa. Prime Minister Kengo wa Dondo had vowed that that city would never be taken, but there you had it: the rebels overran it without a hitch. The characteristic images of the AFDL’s advance showed two long rows of child soldiers in black rubber boots, moving down both sides of the road in silence on their way to a town or city. They were foot soldiers in the most literal sense: children moving on foot. By the time they arrived, Mobutu’s army had already fled, often after a bit of plundering. In Kikwit the inhabitants paid the government soldiers to leave without sacking the town.

51

Once they were gone, the local citizens welcomed their liberators from the east with banners and singing. The democratic opposition was pleased with the military liberation. “The UDPS welcomes the AFDL,” some banners read.

52

The young soldiers who came from so far away and who marched through the streets in such great earnestness were admired for their courage and patriotism.

53

Everywhere they came, new recruits signed up. The Katangan Tigers, whose invasion of Shaba had failed in 1978, joined as well. The AFDL was engaged in a truly triumphal procession.

During grand rallies, Kabila spoke to the newly liberated crowds. For the first time the masses saw the man about whom they had heard so much on the radio. He usually went dressed in black and wore a cowboy hat on his huge, bald dome. Kabila was a robust figure, a man with meat on his bones who laughed broadly and, with one hand in his pocket, exuded an air of ease, even nonchalance. In a firm voice he told overblown stories about his liberation army, spoke of the need for popular militias and urged parents to donate a child to the cause. His charisma was undeniable. Compared to the grumpy old man in Gbadolite, he was a breath of fresh air. He exuded power, but also conviviality. Everything was going to be different now. Rwanda vehemently denied all involvement, but many inhabitants of the interior still suspected that Kabila’s cakewalk had been no purely domestic affair. But all was allowed, as long as it meant being rid of the

vieux léopard

(old leopard). “A drowning man will clutch at any piece of driftwood he can find, even at a snake if need be,” the people in Kikwit told each other.

54

K

ABILA

’

S

AFDL

WON THE SUPPORT

not only of the people, who were tired of Mobutu, and that of Rwanda and Uganda, but also of the United States. Since the end of the genocide, Kagame’s Tutsi regime—thanks to its carefully cultivated role of victim—had gained credit with the American authorities. Embarrassed by a genocide they had not succeeded in preventing, new partner countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands began providing Kigali with lavish support. With Bill Clinton, furthermore, a president had been elected who wanted to force a definitive break with his predecessors’ old, cynical Zaïre policies.

55

He believed in new African leaders, men like Mandela and Museveni—heads of state who in no way resembled the Mobutus, Bokassas, and Idi Amins of yore, he thought—a new generation: might Kabila perhaps be one of those? Although there was no internationally orchestrated approach, the Rwandan army in any event met with no obstruction in carrying out its plans. Just as the French had continued to support the Hutu regime, despite the rumors of genocide, so too did various American services provide logistical and material support for the invading army’s offensive, despite the rumors of massacres.

56

The old-fangled cynicism that the Clinton administration wanted to do away with made way for a new-fangled cynicism: humanitarian in its intentions, highly naive in its analyses and therefore disastrous in its consequences. There was no long-term vision. The confusion was great, the policy off the cuff. The backing for Rwanda and the rebels would unleash years of misery. Kabila must have found it rather amusing: thirty years after being assisted by Che Guevara, he was now suddenly receiving support from the Satan of Imperialism itself.

Mobutu, though, had lost his allies. France briefly tried to help him with a detachment of soldiers, but without any particularly great enthusiasm. He then hoped to turn the tide with a few European mercenaries, but that was no more successful than it had been in 1964. The only ones who showed up were Bosnian Serbs who had fought in the Yugoslav wars, but they were no match for Kabila’s troops.

MAP 8: THE FIRST CONGO WAR: KABILA’S ADVANCE (OCTOBER 1996 – MAY 1997)

Throughout the AFDL offensive, Mobutu spent most of his time in Europe, where he was operated on for prostate cancer (giving rise to a new name for the new batch of worthless Zairian banknotes:

les prostates)

. He resided in Lausanne and at his villa in Cap-Martin. When he finally did return to Kinshasa it was as a deathly ill man who could barely walk. Nevertheless, he was welcomed by a enormous crowd of cheering compatriots. The chief had come back! He was going to save the country! Everything was going to be all right! But it didn’t turn out that way. In the capital the bickering between Mobutu and Tshisekedi went on unabated, as though no massive invasionary force was approaching. They continued to squabble as before over who was allowed to be the prime minister and who was allowed to appoint him, even though half of the country they were squabbling over had already fallen into the hands of others.

Y

OUNG

R

UFFIN, MEANWHILE

, was on his way to Lubumbashi. He and his crew carried their guns and bazookas on their backs. “Everything went by foot. We followed the railroad tracks for long stretches. My feet hurt a lot. We used to pour water into our boots, that eased the pain a little, it let you walk easily again. But it also made your feet sweat terribly. When you took off your boots, your feet stank like a three-day-old corpse!” Soldiers’ tricks and the humor of the trenches.

On April 9, 1997, Lubumbashi—the country’s economic capital—fell to the rebels.

Mzee

Kabila settled in and immediately received visits from international mining companies like De Beers and Tenke Mining, who knew that from then on he would be the one to do business with. The first concessionary mining contracts were signed even before Mobutu was ousted.

57

It was already clear that the scales had tipped. After thirty-two years of dictatorship, a new age was dawning.

For Ruffin, a new phase in the war began. Commander James Kabarebe no longer needed him as his bodyguard. “James said: ‘This is the end for us. I’m going to Kisangani, but you people are staying here with

Mzee

.’ It was the first time I was around

Mzee

. His son, Joseph, was there too.” Father and son stayed in Lubumbashi while the Rwandan Kabarebe led the fighting elsewhere. The victory was within arm’s reach, and that allowed a certain amount of relaxation. Ruffin had fond memories of those days with the president-to-be. “With

Mzee

, the good life started. I’m your father, he said, but never forget your natural parents. He asked where I came from. Bukavu, I said, I was kidnapped by Bugera. Ha, he said, then there’s no more playing priest for you! He liked to tease us. One day we plundered the some storehouses that belonged to the FAZ. I dressed up in a government soldier’s uniform, with leather boots and everything. Is that you,

kadogo

?

Mzee

asked. Yes, I said, it’s me. We stole the enemy’s supplies. You did? He laughed. He shook my hand and said: very good, stay with me.”

With that pat on the head, Ruffin’s incredible youth took another unexpected turn: now he was one of of Kabila’s bodyguards. Within a year he had been transformed from a naive, soccer-playing boy into a worldly-wise young man who stayed on his toes and experienced history live, as it happened. The price he paid for that was fear and the loss of innocence, but each phase brought with it new forms of appreciation. “Kabila liked me. He entrusted his money to me. Ten thousand dollars! He often used to eat with us, right out of his mess tin. Afterward we would arm wrestle and he would be the referee. It was a sport we’d taken part in a lot out in the

maquis

. We never went to nightclubs or brothels: the only lives I knew were those of the seminarian and the soldier. We lived in Hotel Karavia, the best hotel in Lubumbashi.

Mzee

had room 114. The diamond hunters would make appointments to come and see him. He gave me a Motorola.”

In that same hotel room, Kabila regularly received phone calls from his chief of staff, Kabarebe, who was approaching the capital on seven-league boots. Coming down the Congo River, he had seen the two capital cities on their opposite shores and had to ask some local fishermen which one was Kinshasa; otherwise he might have accidentally liberated Brazzaville.

58

Kinshasa was about to fall, Kabila heard in his hotel room. He had never dreamed that things would go so quickly. Two weeks earlier he had flown to Congo-Brazzaville for direct negotiations with Mobutu. Nelson Mandela had called them both to meet on neutral ground, aboard a South African ship in the harbor of Pointe-Noire, but those nocturnal talks had led nowhere. Mobutu was unwilling to budge and Kabila saw no reason why he should add any water to the wine; after all, he had the upper hand. No, Kinshasa would be freed by force of arms and Ruffin would be there to see it happen.