Conquest (53 page)

Authors: Stewart Binns

Harald Hardrada was the last of the great Viking warriors as Scandinavian power in the world began to decline. Prince Olaf, the son of Hardrada and the only senior Norwegian aristocrat to survive Stamford Bridge, became known as Olaf the Quiet and ruled over a peaceful Norway for twenty-five years.

Prince Osbjorn never became King of Denmark. Upon the death of his brother, Svein Estrithson, in 1076, the King was succeeded by five of his many sons in turn: Harald, Cnut, Olaf, Eric and Niels. Svein Estrithson had so many children, all of them illegitimate, that chroniclers lost count of the total.

William ‘the Conqueror’, as he became known, died near Rouen on 9 September 9 1087. He had become so fat that he ruptured his stomach on the pommel of his horse as it stumbled, and never recovered from the injury. Awful scenes followed his death as those around him scrambled to claim his possessions. At his funeral, as they tried to force his body into its stone sarcophagus, it burst open, causing an unbearable stench. His tomb was later defiled four times so that, by 1793, only a single thighbone remained.

Pope Nicholas II was succeeded in 1061 by Alexander II, who was Pope until 1073. However, in 1075 Father Hildebrand became Pope Gregory VII. During the ten years of his papacy, he became widely respected for his wisdom and kindness.

Rodrigo of Bivar continued his military prowess and became Lord of the Taifa of Valencia. He died peacefully in his bed in July 1099. Doña Jimena outlived him and died a few years later.

In 1074 Edgar the Atheling led a force against Normandy from his base in Montreuil-sur-Mer, but it failed when a storm destroyed most of his ships. He finally submitted to William, and was reconciled with him. He became a friend of Robert Curthose, William’s son, fought with the Normans in Apulia and accompanied Robert on the First Crusade in 1100, leading the English contingent. He returned to England and lived into the reign of Henry I. He died in 1125, becoming the only one of Hereward’s contemporaries to outlive him.

Earl Morcar remained imprisoned by William, who, in a moment of remorse on his deathbed, ordered his release.

Unfortunately, William ‘Rufus’, the King’s second son and successor, had him rearrested and he died in prison sometime after 1090.

Even though he is now known as Hereward ‘the Wake’, Hereward of Bourne was not given the suffix ‘Wake’ until many years after his death. The term is thought to come from the Old French ‘wac’ dog, as in wake-dog, the name for dogs used to warn of intruders.

Nothing is known about the fate of any of the survivors of Hereward’s extended family. However, through his daughters, Gunnhild and Estrith, there are intriguing claims linking several modern-day families to Hereward of Bourne. In particular, a family of ancient origin from Courteenhall, Northamptonshire, claims that the present baronet, the fourteenth Sir Hereward Wake, is directly descended from one of Hereward’s twin daughters. The present-day Wakes of Courteenhall are certainly directly descended from a Geoffrey Wac, who died in 1150. His son, Hugh Wac, who died in 1172, married Emma, the daughter of Baldwin Fitzgilbert and his unnamed wife. That wife, it is claimed, was the granddaughter of either Gunnhild or Estrith in the female line from Hereward and Torfida. It is suggested that the woman’s mother had married Richard de Rulos and that her grandmother had married Hugh de Evermur, a Norman knight in the service of King William. It is a tenuous link, but an intriguing possibility.

There are also other claimants to the lineage of Hereward the Wake, including the Harvard family (the founders of Harvard University) and the Howard family (the Dukes of Norfolk and Earls Marshal of England).

The cruelty of Norman rule diminished in the years following the Conquest and although hardly benign in its outlook, England settled into a long period of relative calm and growth. England was never invaded again, but Normandy ultimately fell to the French and was ruled from Paris. Ironically, therefore, the long-term heritage of the Normans became better exemplified in England than in Normandy itself. But England’s future was not entirely cast in the Norman image. The invaders gradually adopted English ways and the English language and although the Norman system of government remained paramount, English culture gradually regained its status.

William’s fourth son, Henry I, became the third Norman King of England in the year 1100. He had married Edith (who took the name Matilda), the daughter of St Margaret of Scotland and her husband Malcolm Canmore. Fittingly, Margaret was the granddaughter of Edmund II (Ironside), King of England in 1016, and could claim fourteen generations of Cerdician royal blood. The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

rejoiced that the new Queen was of ‘the right royal race of England’.

Henry and Matilda’s firstborn son was named William, in honour of his grandfather, ‘the Conqueror’, but also ‘Atheling’ in honour of his Cerdician blood. Thus, less than forty years after Hastings, English pedigree was once more embodied in the monarchy. In the reign of King John, William’s great-great-grandson, much of what Hereward and the Brotherhood fought for at Ely was enshrined in Magna Carta. The ‘Great Charter’ was signed by the King in a meadow at Runnymede on 15 June 1215 and became the first milestone on the road to modern democracy.

The legends of Wodewose, the Green Man, and the ancient beliefs of the peoples of the British Isles in the harmony of the natural world, did survive the coming of the Normans. The Old Man of the Wildwood would be content to know that throughout the length and breadth of England and its Celtic neighbours, the folk memories of the distant past remain enshrined in legends, never to be forgotten. Just as they did centuries ago, they remain part of the art, literature and customs of these islands and help define its unique identity and that of its peoples.

The Harrying of the North, 1070

The true scale of the atrocities committed by King William in northern England in 1070 will never be known, but the brutality of the crimes shocked the whole of Europe. Even scribes writing under Norman rule could not hide their contempt for what had been done.

Within a lifetime of the events, the Anglo-Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis wrote the following account. He described the event in the first person, thus emphasizing William’s personal responsibility.

I fell upon the English of the Northern shires like a ravening lion. I commanded their houses and corn and all their chattels to be burnt without distinction and large herds of cattle and beasts of burden to be butchered wherever they were found. It was then I took revenge on multitudes of both sexes. I became so barbarous a murderer of many thousands, both young and old. Having therefore made my way to the throne of that kingdom by so many crimes, I dare not to leave it to anyone but God.

Orderic Vitalis’ estimate of the number of English dead in the Harrying of the North was 100,000. This figure was also reported in other chronicles of the time.

Acknowledgements

To the wonderful friends and outstanding professionals who have helped me transform a vague idea and a very amateurish transcript into a moderately decent story, my eternal thanks and gratitude.

Genealogies

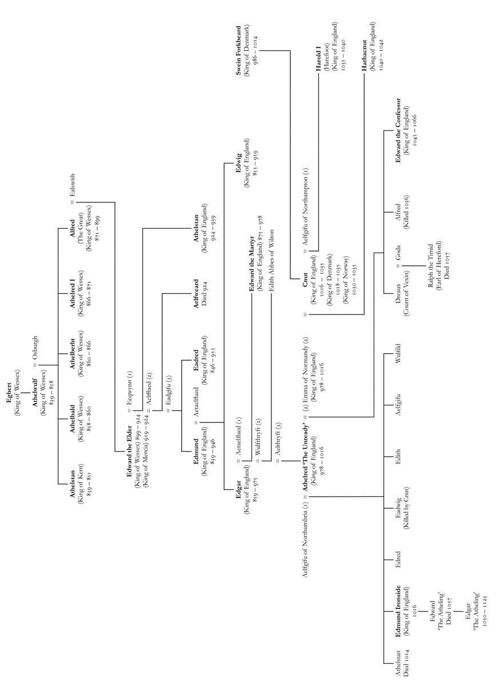

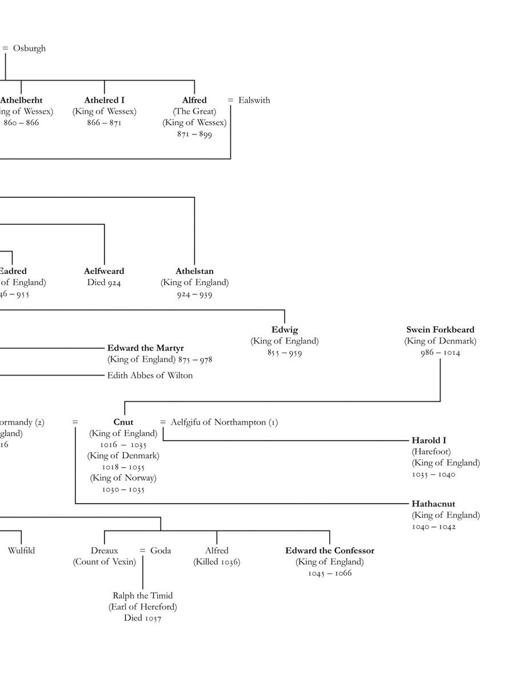

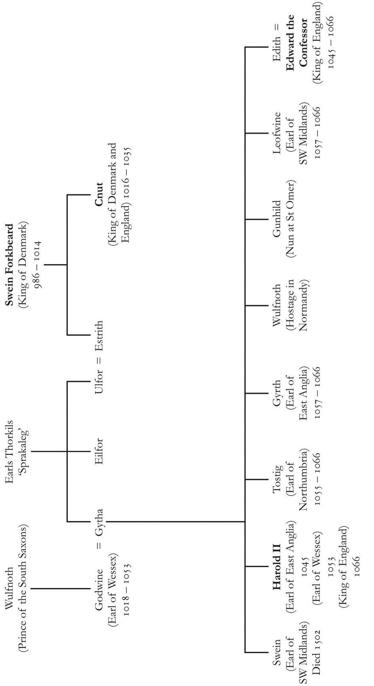

The Lineage of Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex and King of England

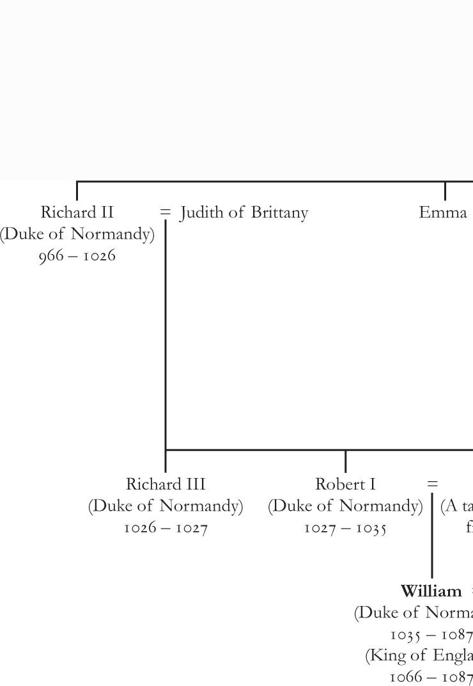

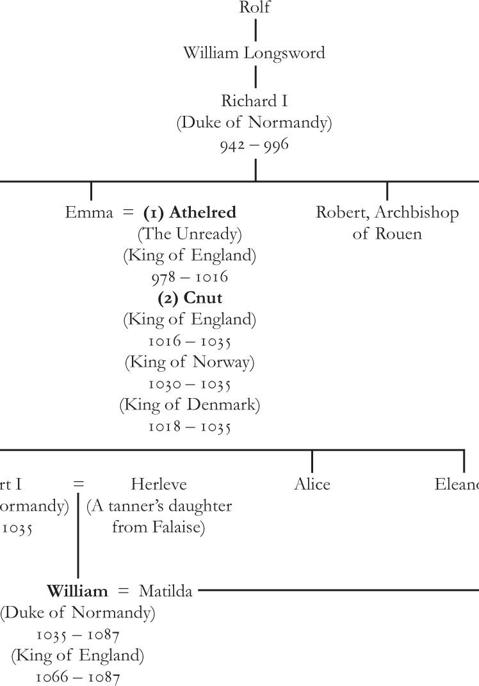

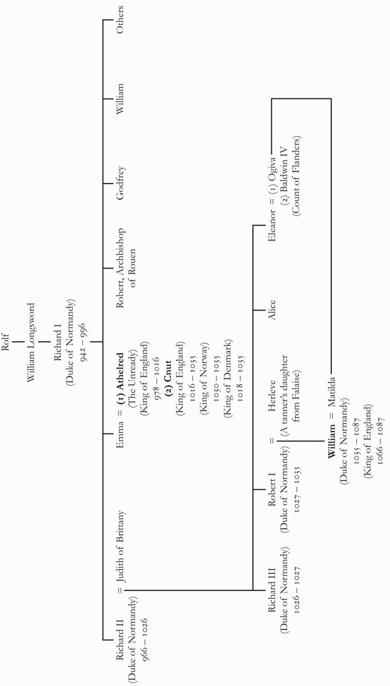

The Lineage of William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy and King of England

The Lineage of Harold Hardrada, King of Norway

The Descendants of Hereward of Bourne and Torfida (conjectural)

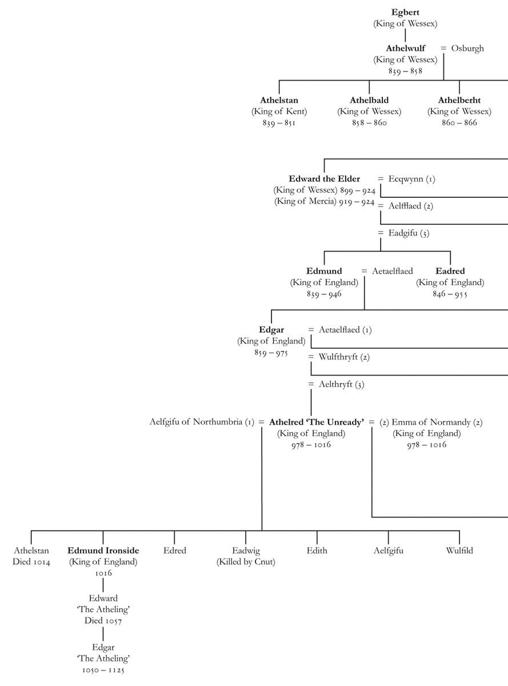

The Lineage of the Cerdician Kings of Wessex and England from the Ninth Century to Edward the Confessor

The Lineage of Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex and King of England

The Lineage of William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy and King of England